Shows

Maia Ruth Lee’s ambiguities in “The skin of the earth is seamless”

Maia Ruth Lee: “The skin of the earth is seamless”

Tina Kim Gallery, New York

Apr 6–May 6

For those who have spent time at an airport’s baggage reclaim in a South or Southeast Asian country, Maia Ruth Lee’s exhibition at Tina Kim Gallery, “The skin of the earth is seamless,” replicated a distinctly familiar scene. Crowded against a sidewall and immediately visible upon entering the gallery was a bloated pile of cardboard boxes, suitcases, and amorphous mounds, variously wrapped in plaid tarp, vibrant plastic, recycled burlap, and creased strips of packing tape. Each bound by intricate latticed cord, these packages swell out of their gridded enclosure. They often dot the baggage carousel in countries that have a substantial population who live abroad, indicating an individual’s return to their natal country, and may contain personal possessions or gifts for loved ones. But stacked precariously in a gallery space—devoid of the eager energy of the expectant families and friends which enliven an arrivals hall—they appeared abandoned or misplaced. Scattered in smaller configurations across the floor and inspired by the carryalls in the airports of Lee’s childhood in Kathmandu, the works from the ongoing series Bondage Baggage (2018– ) seem to be awaiting collection but, in the meantime, confined to lost luggage limbo.

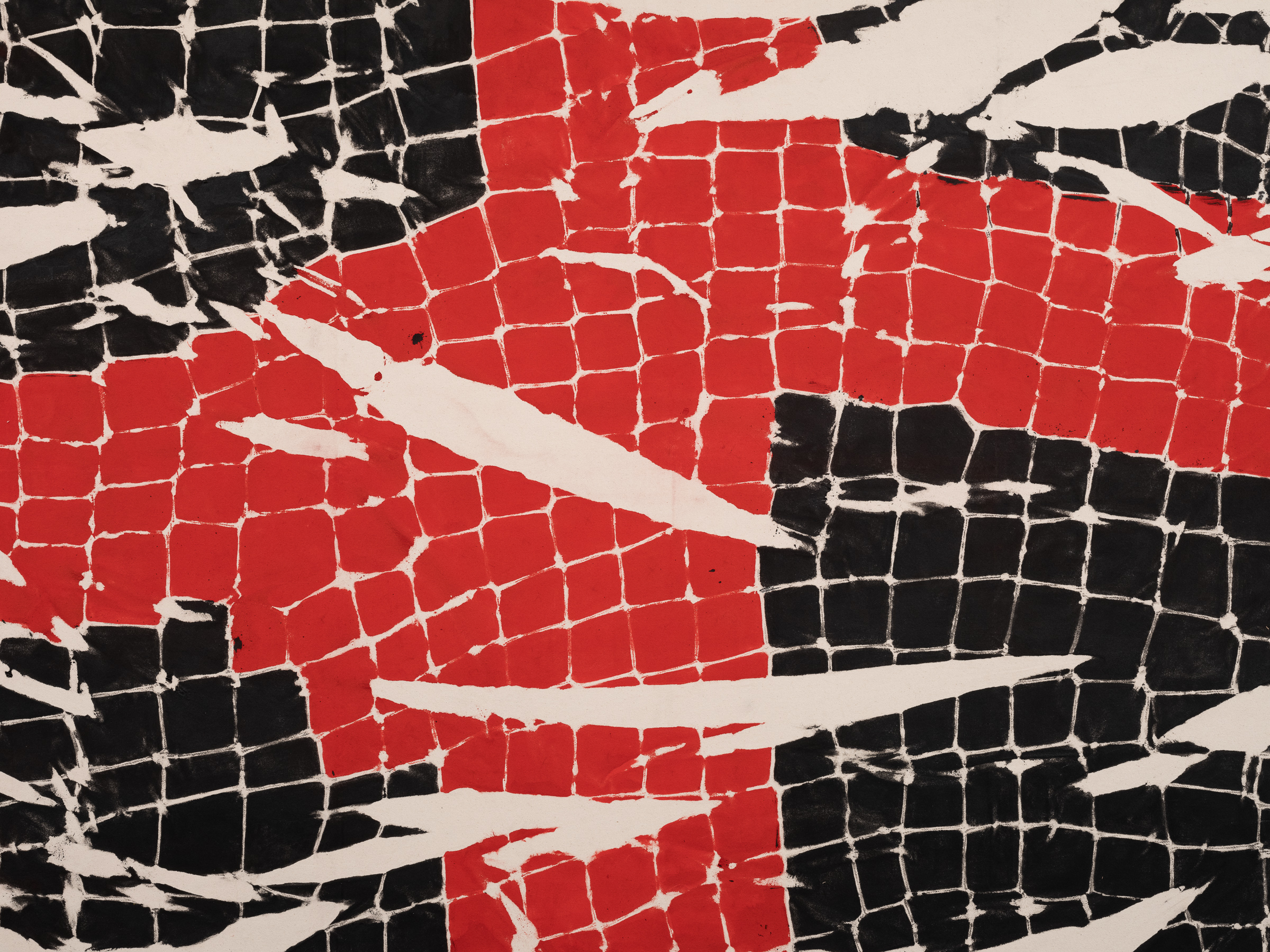

On the surrounding walls and continuing into the gallery’s back space, lofty paintings composed of cerulean, red, and black India ink erupt from their center, with edges that flare out into sharp tendrils. The production of these works is threefold. Lee rubs ink onto canvas-based Bondage Baggage sculptures, cuts away their restraining net, and stretches the canvas. The final images produced are cartographic: a sprawling mass that is punctuated by the negative space of the deconstructed sculpture’s webbed cord, akin to longitude and latitude on a map or the rigid borders of nation-states. The discarded rope, still warped to the contours of its previous contents, are dispersed throughout the room.

Two works from Lee’s wall-hung iteration of Bondage Baggage feel significantly hostile. B.B.L Red Umbra 1-41 (2023) and B.B.L Red Umbra 1-31 (2023) feature an overwhelming black expanse dissected by bands of bright crimson. Violent gash-like slits of raw canvas appear where ink failed to stain. It recalls, unintentionally, the discriminatory practice of redlining, where neighborhoods with primarily Black or low-income residents marked “high risk” are denied financial services, and the choropleth maps used to visually communicate climate catastrophes, viral surges, war zones, poverty levels, and political allegiances. What results from each classification? The inevitable forced movement of disenfranchised or oppressed populations.

The sculptures and paintings themselves mark a fierce presence of the artist and her labor, but it is only through what is absent that they come into full consideration. Although Lee hopes to emphasize the generative possibilities that emerge out of migration, against a global political backdrop defined by lethal territorial control and a perilous international labor force, it is hard to ignore the conditions of racial capitalism and neoliberalism through which these carriers have evolved. As the scholar of gender theory Neferti XM Tadiar writes in Remaindered Life (2022), this is nowhere more evident than in the countries in South and Southeast Asia, where large populations have been deemed expendable and exportable through processes of insecurity, inequality, and constant dispossession. What remains of the personal is lumped together and secured with tarp, with the hope that life can be extended for one more day.

Projected in the corner of the gallery’s front space was a looming video work. The Letter (2023) is a collage of home videos taken by Lee’s father during her upbringing in Nepal, overlaid with text from letters she sent to friends during the pandemic, a time that saw her experience her own migration from New York to Colorado. Tumbling waterfalls, airport runways, mundane labor, grand vistas, and creative endeavors all feature in this personal reflection of the joys and struggles of arduous relocations. “I want him to be like water, to know no bounds, to flow effortlessly,” Lee recounts, detailing her hopes for her own child as he grows. Over the course of the 22-minute video, transgenerational memories meld past, present, and future into one. The title of the show is most pertinent here. “The skin of the earth is seamless” is taken from Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands / La Frontera (1987), a seminal work wherein the activist and scholar conceptualizes a cultural identity for those who inhabit the border between Texas and Mexico. The duality of here or there is transcended and a plurality of selves emerges, making way for the co-existence of contradictions. This ambiguity—of migration and its varied truths—is precisely where Lee’s work lies: full of the despair, intimacies, and delights that make up life as a drifting diaspora.