Shows

“Made in North Korea: Everyday Graphics From the DPRK”

Nicholas Bonner set up Koryo Tours—a travel company specializing in trips to North Korea—in 1993, six years after the reclusive state first began to allow western tourists limited access to its attractions. Since then, Bonner has built up a significant collection of ephemera from the self-proclaimed workers’ paradise, much of which was on display for the first time in “Made in North Korea: Everyday Graphics from the DPRK” at London’s House of Illustration.

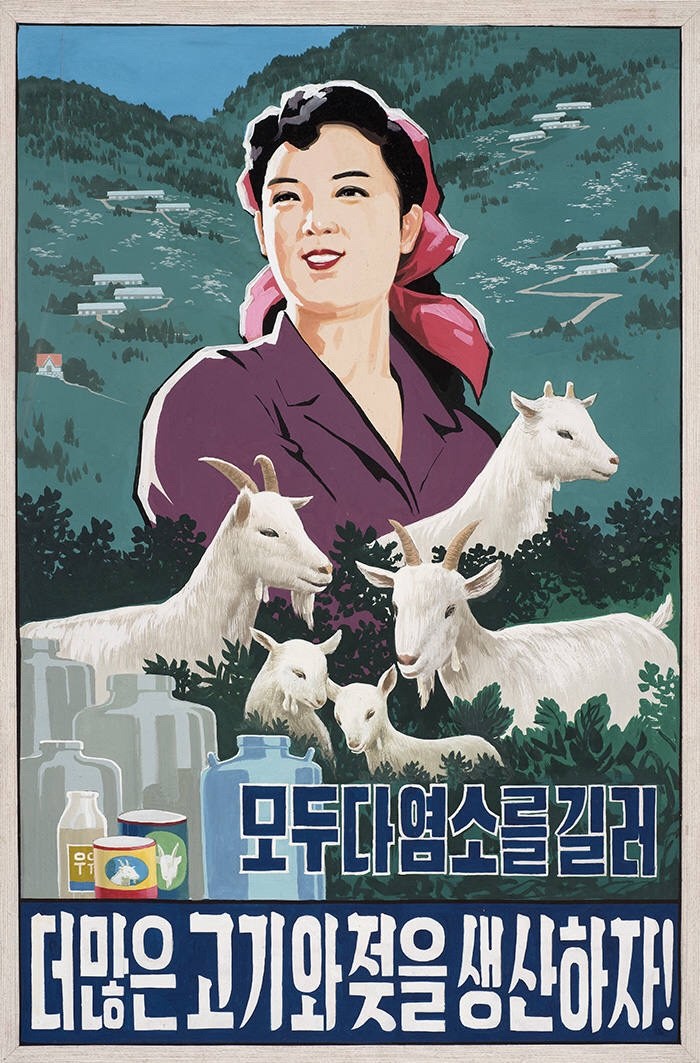

For many, the draw of an exhibition such as this is the chance to gain a rare glimpse into the day-to-day realities of a closed country, and, yet, it is questionable whether certain forms of design—posters, postcards and comic book covers—are really apt to provide this. Such overt media, after all, are less a reflection of reality than of ideology, and this goes for analogs found in western and capitalist countries as well, where the call to consumption channeled through the practical and identarian needs and desires of the individual is the basis for most advertising. Advertisements don’t reveal reality; they present an alternative, idealized reality that, in order to drive consumption, must always remain just out of reach. Hence the first of several interesting contrasts that can be gleaned from Bonner’s collection: in the dozens of clearly Soviet-influenced posters on display—most of them hand-painted in state-run artist studios such as Mansudae in Pyongyang, which employs 1,000 artists—the call is not to consume, but to produce, and the reality being sold is of societal, not individual, betterment. The second person singular imperatives of slogans like Nike’s “Just Do It,” or Evian’s “Live Young” are here replaced with the first person plural, somewhat less catchy, “Let’s all rear more goats . . . Produce more meat and milk!” accompanied by the image of a woman in a bucolic setting, surrounded by said animals and gazing contentedly into space, or “According to the demands of the seasons, the province and the classes . . . Let’s adapt our offerings to the needs of consumers!” written beneath a picture of a smiling female textiles worker.

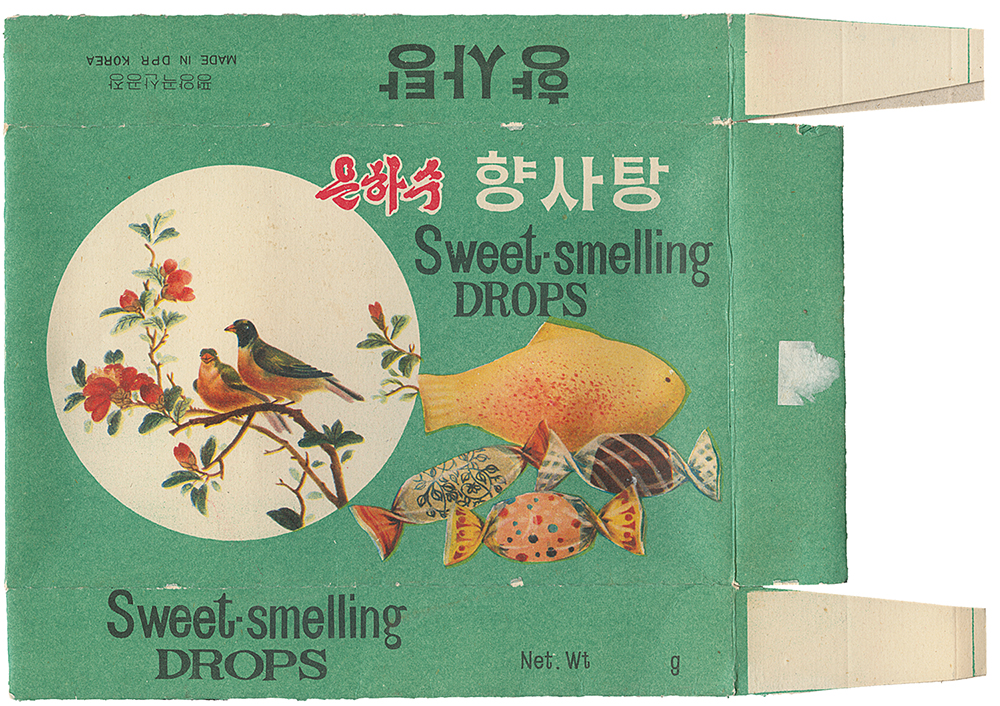

In another room, the focus shifted and visitors were able to look a little closer at life inside North Korea through objects of consumption themselves—or, rather, the packaging they came in. Cigarette packets marketed at different sections of the republic’s society—one kind popular with heavy industry workers, another with soldiers—were displayed alongside candy boxes and labels from tinned goods produced in the early 1990s, often with descriptions in several languages to facilitate export to foreign communist states. The tin-labels, with their vibrant images of the various goods contained within—such as a hanging apricot or boggle-eyed trout—were notable for their bold but simple design.

In several sections of the exhibition, traces of the country’s political history could also be seen. In a display case of items available to tourists, for instance, was a phrasebook opened to a page where, as part of a lesson on word order in Korean, the example sentence was “Yankees are wolves in human shape.” Similarly, the impressive collection of over 100 comic books, such as The Scared [Japanese], reflected North Korean sentiments over the brutal Japanese occupation of the peninsula from 1910 until 1945. While the majority of the comic book covers on display exemplified a sense of besieged militarism, often showing soldiers in heroic poses aiming firearms out of the frame, with titles including “The Last Ditch Fight of the Remnants of a Defeated Unit,” or “He Was A Revolutionary Soldier Who Was One Against A Hundred,” there were a few examples with apparently more civilian subject matter. The Pollen Brought Back By Bong Bong The Bee, featuring a cartoony, half-human, half-apian hero on the cover, or The Maestros of High Technology, with its three comradely heroes in high-tech suits, each appeared to be aimed at the general public, and pushed the message of collectivist responsibility.

As might be expected, there was little here that was not, in some way, propagandistic, but the exhibition’s curators did well to maintain a sense of neutrality. Design is, after all, often the vehicle for ideology—be it capitalist or communist—and, at a time of such high tension between North Korea and the West, it was refreshing to see these rare items presented as things in themselves, contextualised with descriptive rather than political accompanying texts.

“Made in North Korea: Everyday Graphics from the DPRK” is on view at The House of Illustration, London, until May 13, 2018.