Shows

Lucid Fractions: “Customised Postures, (De)colonising Gestures”

Jan 19—Feb 18

“Customised Postures, (De)colonising Gestures”

Gajah Gallery

Singapore

Curated by Indonesian art historian and photography scholar Alexander Supartono, the exhibition at Gajah Gallery Singapore broached the discourse of decolonization in dual segments, as expressed by its title “Customised Postures, (De)colonising Gestures.” One part of the show displayed how colonial power historically manifested in the postures of their photographic subjects, while another presented how 14 contemporary artists from Indonesia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Malaysia engage in the act or process of decolonization.

“Customised Postures” was broken into six sections: “Ordered Poses,” “(Colonial) Environmental Portraits,” “Scaling Postures,” “In Search of (Traditional) Postures,” “Customised Postures,” and “The Triangle.” The first four were positioned near the entrance door; the last two were placed on the farthest wall with Ashley Bickerton’s Auntie Painting (2015) between them. The exhibition’s interweaving of archival sections with contemporary artworks opened up the potential for more enriched dialogues and narratives. However, while the two parts appeared interconnected in the title and accompanying exhibition text, their physical arrangement was more disparate.

-009.jpg)

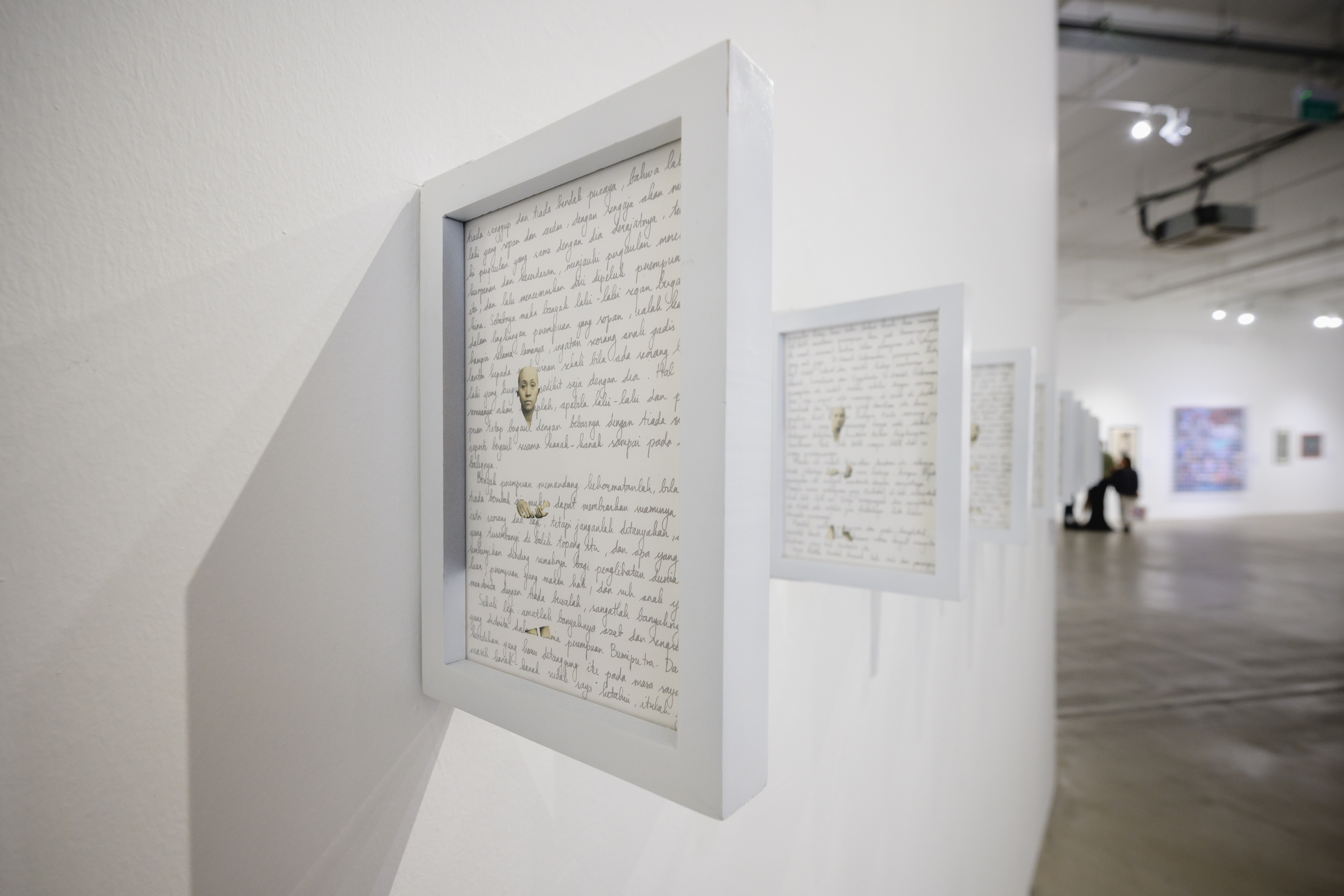

The photographs in “Customised Postures” suggested how “women were the most objectified subjects regardless of their status in society.” Unseen from this section’s vantage point, across the room were two archival inkjet prints from the works series Mlaku Ndokok (To Walk Squatting) and What Am I Going To Be When I Grow Up? Raden Ayoe Of Course (both 2015) by Indonesian artist Abednego Trianto Kurniawan. These referenced the noblewoman Raden Adjeng Kartini, who advocated for Javanese women’s emancipation under Dutch rule. Placing Kurniawan’s pieces beside the “Customised Postures” section could have expanded notions of Southeast Asian women’s portraiture.

-025.jpeg)

As for the strength of the exhibition’s design, the placement of the sculptures Anatomi Kerja (The Anatomy of Work) (2023) by Indonesian sculptor Budi Santoso as the centerpiece effectively anchored the surrounding artworks. Consisting of naked human figures atop the sickles, the work alluded to power (or lack thereof), labor, and agriculture, symbolizing the major economic sector of many Southeast Asian countries. Further amplifying Santoso’s sculptures was the context behind the combination of readymade and sculptural elements—human figures modeled after the anthropometric photographs of Sumatran plantation workers taken by a physician working for the Dutch East Indies and the second-hand plantation sickles the artist gathered for the work.

This contextualization was provided in the supplemental texts for every artwork in the show, something essential for any initiative revisiting and challenging colonial histories. Although some works were vague in their historical inspiration, such as Indonesian artist Handiwirman Saputra’s Lelaki dan Garis Putus — Putus (Man and The Broken Line) (2024), its material abstraction interfaced with 1973-born Rudi Mantofani’s hyperrealist painting Cahaya Nusa (Ray of the Nation) (2023) that probed territorial distortions as a result of violent conquests. Again, however, these were not in visual proximity to each other, marking another potential connection that could have been further explored in the spatial design.

-014.jpeg)

Given that Supartono is one of the principal investigators of Photography Unbound, a Getty research project where historical photographs are computationally analyzed, the receptiveness to new technology in art surfaced in the two works that employed artificial intelligence. While such inclusion reflected current experimentation in artistic practice, its relevance to the show required more fortification. For instance, Filipino artist Jao San Pedro’s Portal (2023) video series from her initial solo exhibition touched on personal and technological loss, topics that were somewhat tangential to the exhibition’s primary subject matter of decolonization.

Conversely, A Patchwork Tells A Thousand Histories (2023) by the Sydney-based, Singapore-born artist Suzann Victor was a noteworthy artwork with a firm thematic link. The two-meter lenticular print was immediately visible upon entering the gallery space. Square acrylic lenses tessellated a colorful tableau: a refracted collage of trees, structures, animals, and people. While the artwork’s text indicated that the images were based on old postcards with the Singapore River as the backdrop, even when viewed on the side through the 15-centimeter gap between the canvas and the lens, one still could not see the complete picture.

-028.jpeg)

Victor’s “lenscape” mirrored the overall takeaway of the show: images of colonial histories were viewed in fragmented perspectives, dispersed in several lucid fractions and few cloudy areas.

Lk Rigor is a writer based in Manila.