Shows

Lee Kit and Cui Jie’s “The Enormous Space”

In 1989, British author JG Ballard published The Enormous Space, a short story about Gerald Ballantyne, a man who withdraws from the world and fortifies himself in his abode, not due to agoraphobia but to “experiment” with reducing his immediate environment to nothing but his house, committing what is in effect a slow suicide. OCAT Shenzhen’s latest exhibition took this tale as a departure point, with the presentation going in two divergent directions: Chinese artist Cui Jie showed us how architecture at an ambitious scale can inspire, while Hong Kong-born Lee Kit placed us in an intimate, domestic setting.

Architecture first and foremost forms the physical foundations of societies and communities, but it can also be a moral force, and can cement the mythologies of a nation. Some naturalized Americans can still recall seeing Lady Liberty for the first time as they approached Ellis Island. The Arc de Triomphe de l’Étoile was built to honor those who perished in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Even the Great Wall of China, originally erected to deter raiders from the Eurasian Steppe, serves as a symbol of the country’s tenacity. In the boomtown cluster found in the Pearl River Delta region, where the world’s factory once existed, and where skyscrapers were raised in a flurry of economic strides, monuments that mark those achievements are bizarrely absent.

This led Cui to reimagine some of the important but dull buildings in her country, injecting flourishes into otherwise unremarkable edifices. Guangzhou Telecom Building (2017), a 3D-printed miniature copy of the titular office headquarters, carries the addition of three figures—arms outstretched, hair blowing in the wind—jutting out from one side of the tower, two of them taller than the building itself. There is a sense of grandeur that is normally reserved for victory monuments, at a scale intended to promulgate the importance of this locale. Cui does the same with several other office towers, marrying stellar or avian Art Deco elements with humdrum, blocky structures, and presents them in sketches or as 3D-printed sculptures.

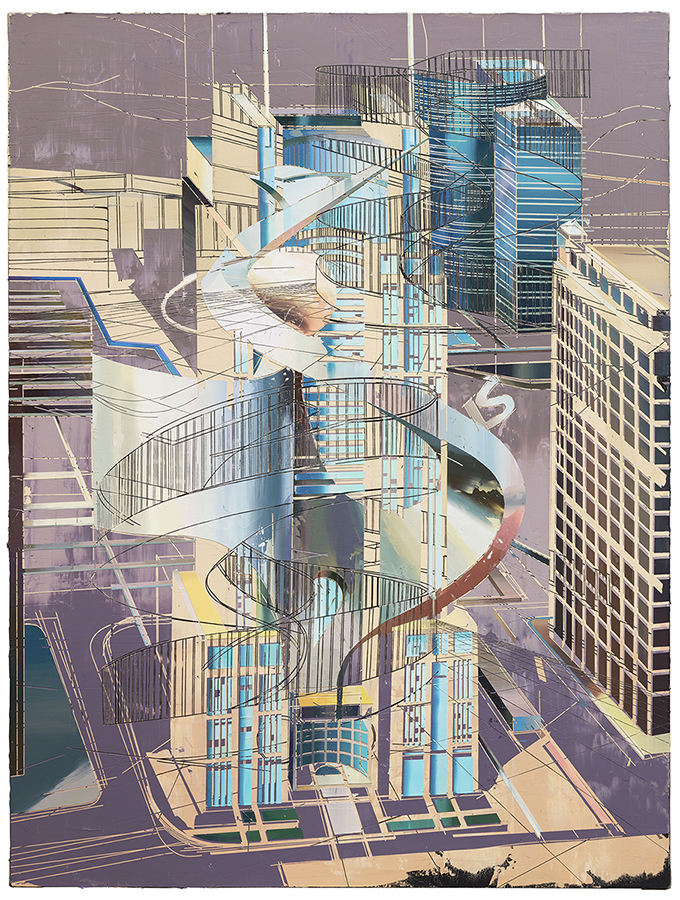

The artist also renders her visions in acrylic and oil paints on canvas, as in Shanghai Bank Tower 2 (2017). Cui not only reproduces the original structure with the exactness of an architectural draftsperson, but adds new purpose to the static, drab building. Gouges and troughs in the paint’s surface form the outlines of architectural flourishes, or even the plan of a second structure, extending Cui’s designs for a world filled with constructions that inspire and celebrate, not merely house.

The other half of the show was filled with works by Lee. If Cui’s presentation was packed with grand scales and a god’s-eye view of urban planning, then Lee aligned himself with the premise of “The Enormous Space” in that the artist sequesters scenes from the outside world indoors. Melancholic impressions lingered over Lee’s setup. In one chamber, a screen and speaker hug a wall, as they loop the chorus of Let Me Get There by dream-pop band Hope Sandoval and the Warm Inventions, featuring American songwriter Kurt Vile, with repeated lyrical delivery of the song title. One room over, a projection of barely lapping waves is wistfully subtitled: “Staring at the boundless sea, / full of fatigue, / but no words and no tear. / Staring at the sky, / affections filled my mind.” A construction lamp aimed directly at the same surface washes out the footage, which hits a corner in the room and folds over a perpendicular wall.

Another projection shows a houseplant swaying in the air, though a section of the image is obscured by a sheet of paper that covers half of the lens. Yet another projection—this time, simply of a blue wall with subtitled text reading “I didn’t know that I was dead”—falls on one vertical surface, but with its right edge caught in the next room. Given the exhibition’s starting point, it isn’t a stretch to imagine these scenes as visual solace for a recluse, though the many imperfections in their elocution remind us that we are in a self-designed, self-imposed prison-paradise, with the sharp edges where walls meet slicing into our perception of space. Moving forward in the presentation, we read other lines: “It is sad to be a piece of work.” “The darkness is not the sky.” Suspended headphones play Gnarls Barkley’s Crazy, with a final projection blinking in sync with the beat. We can’t actually see what’s shown in the video until we remove the headphones and walk forward—it’s of an air conditioner and the song’s lyrics, shown in English and Chinese—leaving the full track behind, its sound fading with each step.

As we progress deeper into the recess created by Lee, we are not unlike the protagonist in Ballard’s tale, retreating into smaller sections of his house, cleaving off the outside world. Ballantyne let madness take over, mistaking it for epiphany, finally sharing a freezer cabinet with his wife’s corpse, where “a palace of ice will crystallize around us.” But there was no mania, fixation or lunacy in “The Enormous Space.” Rather, calculated displays tugged us along. The outside world might be scary, but there was a clear path leading toward it, illuminated by bright green emergency exit signs.

Lee Kit and Cui Jie’s “The Enormous Space” is on view at OCAT Shenzhen until April 8, 2018.