Shows

Kim Tschang-Yeul’s “Kim Tschang-Yeul”

Artist Kim Tschang-Yeul has been painting water drops for more than 45 years. What began as a spark of inspiration soon became a signature motif that differentiated him from his Korean compatriots. With nearly two dozen paintings spanning half a century of work on view, the retrospective at Almine Rech Gallery New York traced the visual progression of the artist’s practice, while also alluding to an autobiographical journey of reminiscence and acceptance.

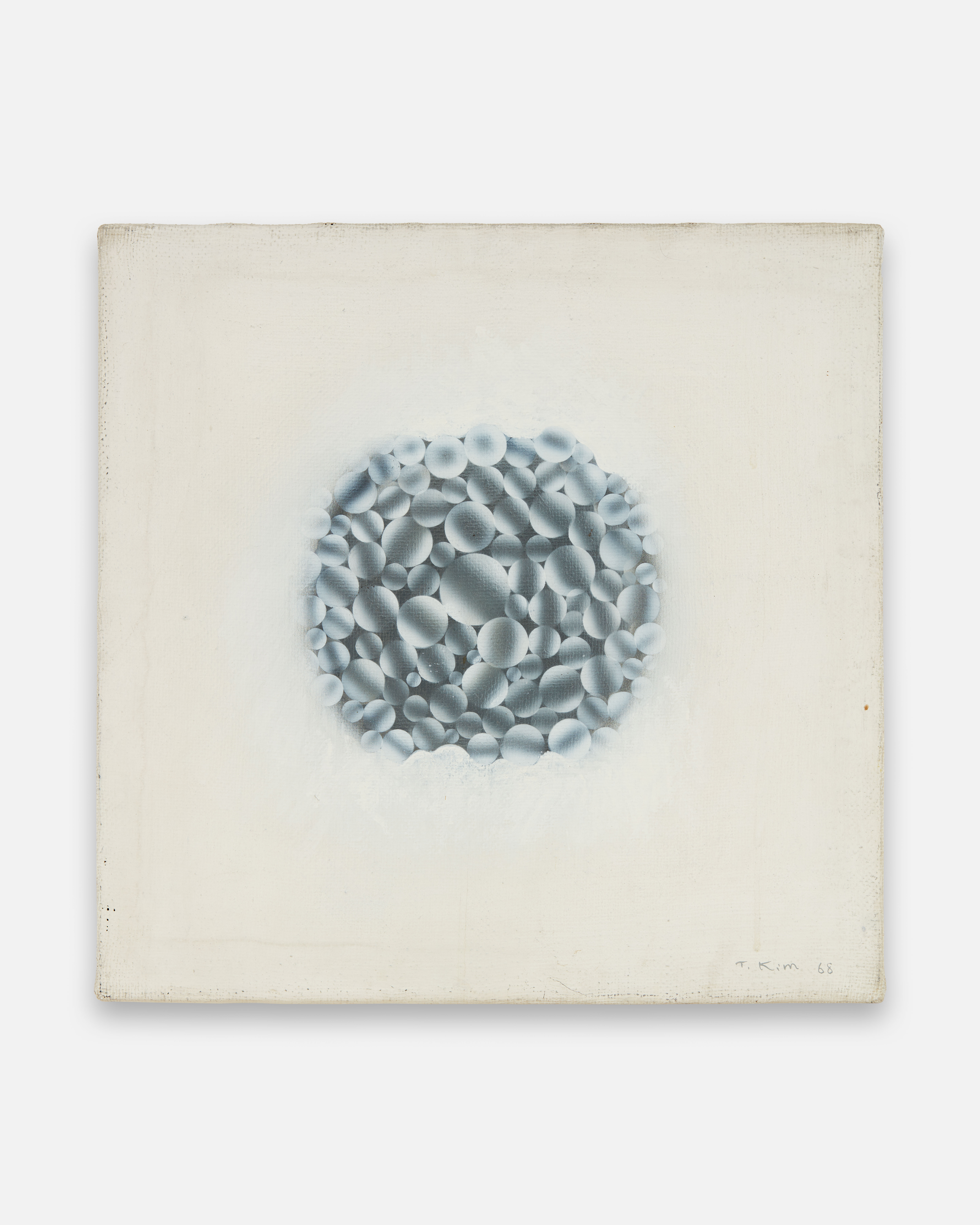

Born in 1929 in then Japanese-occupied North Korea, Kim began his career as an artist in Seoul before moving to New York City. When Kim painted Phenomenon (1968), the earliest work included in the exhibition, he had been living in the United States for three years. Clustered together like air bubbles or blood cells coagulating on the canvas, the dusky circles illustrate a subtle but perceptible shift from the looser abstraction of the Korean Art Informel movement, which he and his peers, such as Park Seo-bo and Ha Chong-hyun, were, at the time, leading toward more defined geometries. This move from chaotic fragmentation to reinvention was prompted by the artist’s new environs and the thriving society that he found himself in—a world away from post-war Korea—its consumerism and irony reflected by the tail-end of the Pop Art heyday.

Building upon the fluid shapes with which he was already experimenting, Kim then began painting water after moving to Paris. A surreal example can be found in the moody Événement de la nuit (1972), where a single oversized water drop hangs, its shadow projected against the dark ground. Within the droplet is a reflection of the window of his studio. According to the artist’s son Oan Kim, his father’s “eureka moment” occurred early one day in the studio when he sprayed some water on the back of a painting. Upon seeing the water droplet shining in the morning light, he knew he had found his subject. Similarly, Waterdrop (1974) features a single drop, this one running down the bare canvas rather than hanging midair. Light illuminates the globule, casting a realistic-looking shadow across the surface. In Waterdrops (1974), another painting from the same year, multiple small beads of water appear to sit on raw linen. The trompe-l’œil effect, facilitated by an airbrush, would continue to be favored by Kim.

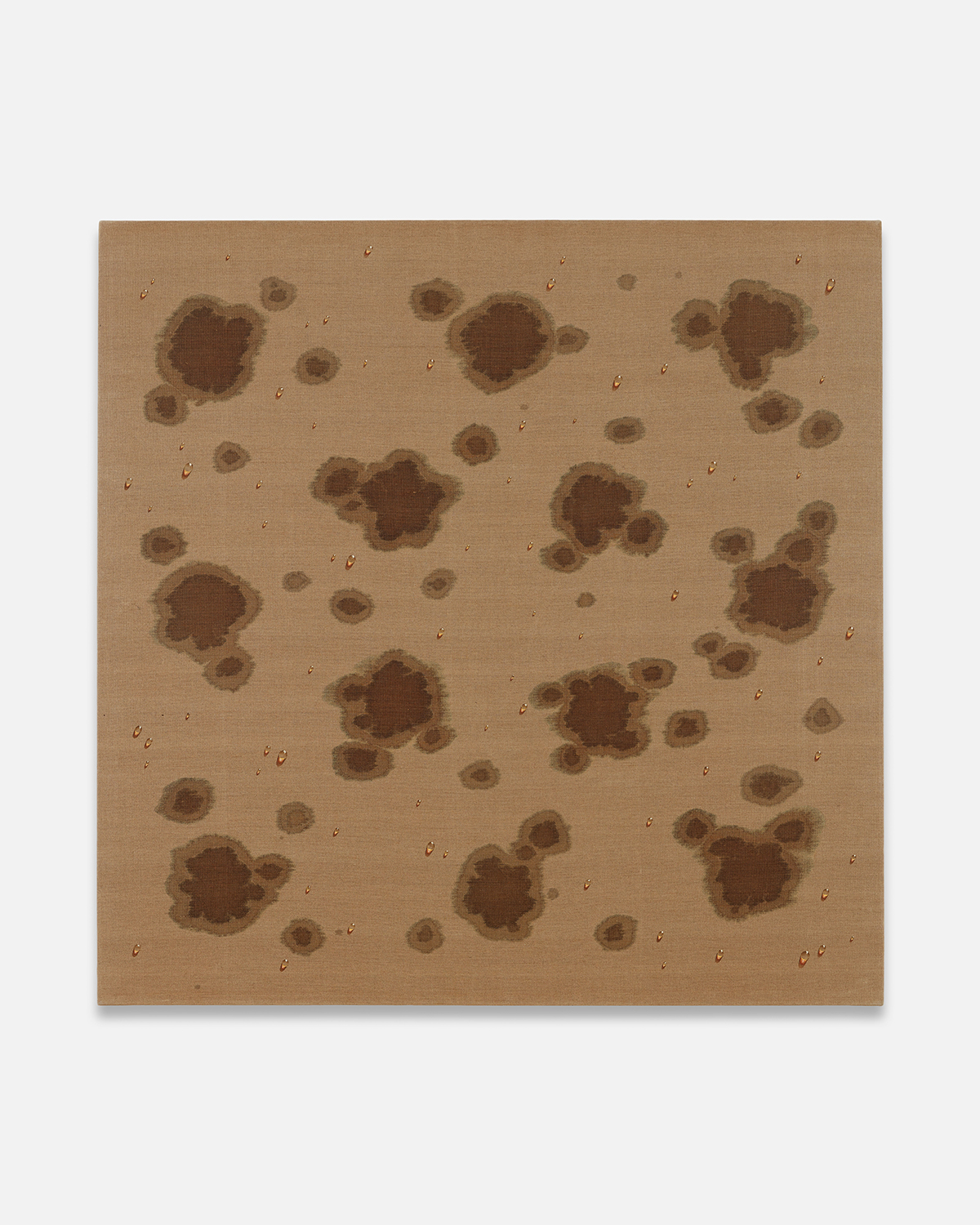

Why water drops? To answer that question, the viewer can look to the accompanying water stains Kim often paints. Waterdrops (1980) features large, gray splotches, which seem to be spreading across the canvas fibers, foreshadowing how water is absorbed and evaporated, and acknowledging the substance’s transient states. The monochrome stains sit in contrast to the drops themselves, which produce the illusion of radiating light through different shades of paint—yellows, oranges and, in other instances, blues. Found in the philosophies of Buddhism and Daoism, the concept of balance—between light and dark, wet and arid—reflects the artist’s cultural upbringing. It also speaks to the emotional past of an individual who has survived the trauma of colonization, conflict and displacement. Kim’s son called the water drop “an eternal requiem for his friends who died during the war.” Despite the element of mourning, the younger Kim clarified that his father resists referring to them as tears.

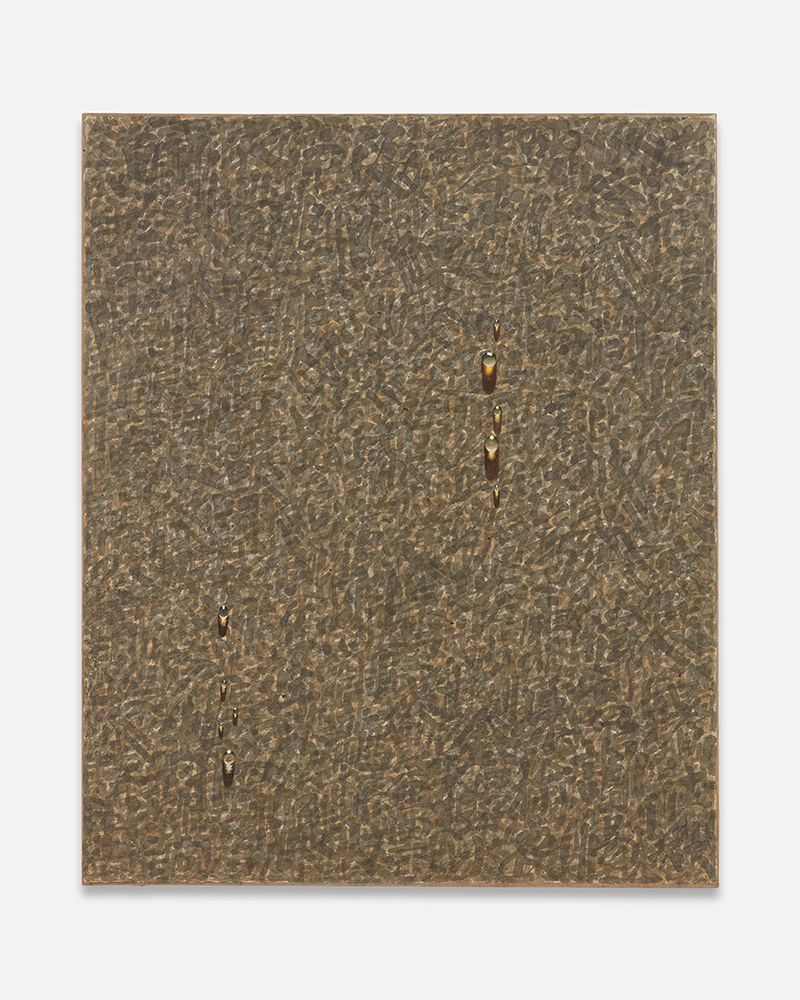

The “Recurrence” series (1989) perpetuates the feeling of nostalgia, both culturally and personally. Here, the water drops appear camouflaged by a rambling pattern, reminiscent of an overgrowth of branches and trees. Kim created the textured background, consisting of black ink on rice paper, by repeatedly writing Chinese text from the Book of 1,000 Characters until they overlapped. The process is a nod to the traditional practice of calligraphy that his grandfather taught him, and which served as his first experience of picking up the brush.

Throughout the decades, Kim has played with context, changing the types of materials he would paint the beads of water on. Waterdrops (1979) pushes the hyperreal, with two drops of water painted on an actual tree leaf, while Waterdrops (1986) gestures not to nature but to our manmade reality by showing a smear of black paint and droplets across a page of French newspaper Le Monde. The newest work from 2017 reveals a return to the simplicity of water drops on canvas, though their execution has become less precise and more impressionistic in his old age. On the one hand, the artist’s steadfast dedication to painting the same thing over and over may seem to be a Sisyphean kind of penitence. On the other, his art can be interpreted as a mode of meditation and of finding peace within one’s mind.

Mimi Wong is a New York desk editor of ArtAsiaPacific.

“Kim Tschang-Yeul” is on view at Almine Rech Gallery, New York, until 14 April, 2018.