Shows

“Interweaving Travelers” at New Taipei City Art Museum

“Interweaving Travelers”

New Taipei City Art Museum

Nov 10, 2023–Mar 3

Before gaining notoriety as “the town that looks like Spirited Away,” Taiwan’s Jiufen was emblematic of the beauty of a country recovering from years of martial law. Taiwanese photographer Cheng Shang-Hsi’s Jiufen series (1959–66)—which welcomed audiences to “Interweaving Travelers”—captures an overcast portrait of the years between the decline of its once-booming gold mining industry and the revitalizing throngs of tourists that wind their way through the mountains into town. In contrast to the riot of plastic that greets visitors today, Cheng’s subdued images of reedy hilltops and stark mountain passes highlight the magnitude of the town’s development.

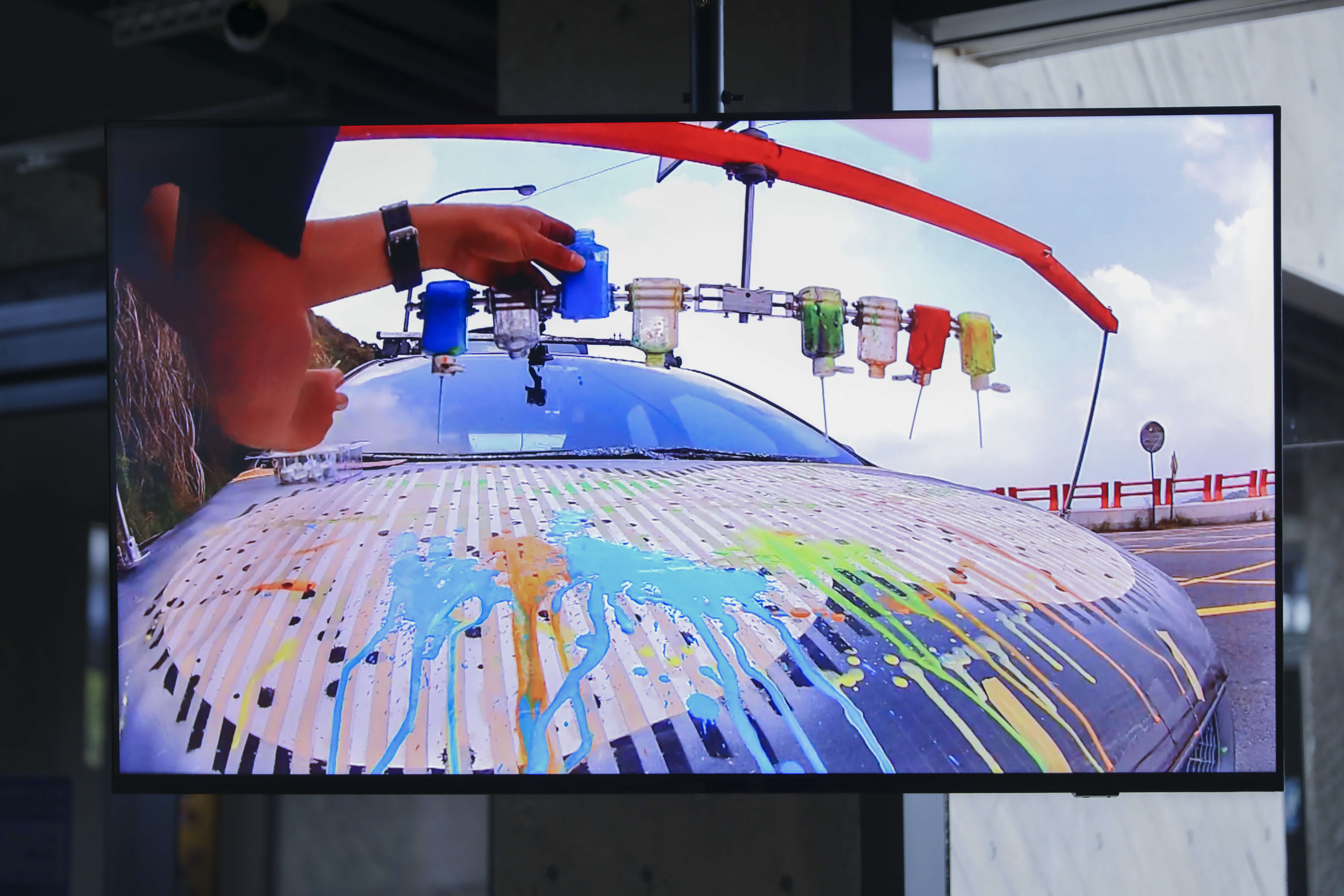

“Interweaving Travelers” departed from the premise of social progress spurned on by greater mobility and access to place, with the ongoing transformation of Jiufen serving as a prime example. In the local context, the exhibition was compelled by curiosity in its pursuit of what curator Hsieh Feng-Rong termed “the radical essence of mobility.” Like an epilogue to Cheng’s Juifen series, Hsieh Mu-Chi’s Sketch from Hill Road series (2012) paints a visceral picture of Taiwan’s mountain highways, highlighting the capacities of these lines of mobility carved into the island by the state. In Sketch from Hill Road: Outside the Car (2012), the artist rigs a canvas and a paint dropper to the hood of a car to study the forces that animate these channels; the hood-shaped canvas created in the wake of this joyride is like a dashboard display perceiving the land with a new, incomprehensible gaze that operates only at maximum velocity.

Despite this attention to local dynamics, various attempts to explore more abstract global mobility felt crudely self-indulgent and hampered the exhibition’s ability to assert a credible politic. Lee Kit’s site-wide installation We have all the time in the world (2023) wrenched washing machines and refrigerators from their domestic context and left them battered, strewn about NTCAM’s sleek architecture, and abandoned before the backdrop of one of his signature hazy clip-montages, soundtracked by the smooth jazz crooning of Louis Armstrong.

More potent and legible testaments to violence have always been available to us, and the recent outpouring of images of violence and atrocity in Gaza, Congo, and Sudan have cast a spotlight on the ineptitude of Lee’s atmospheric approach. The work’s ambient blandness confirmed the resounding necessity of eschewing ambiguity in favor of concrete responses to such brutality. Lee’s sculpture-parking of the dilapidated shells of real-life objects around the premises removed them from any context that might demand action—the rubble of a family home, perhaps—and restrained any volition toward resolution. And in what curator Hsieh Feng-Rong frames as his attempt to cast “the endless conflicts that persist in the world” simply as “subjects of gazing,” Lee’s work inadvertently revealed a stagnation in the mobilization of empathy vital for change.

Indeed, while Lee’s offering is tonally indistinguishable from the impersonal site of mobility that is the corporate airline lounge, Huang Hai-Hsin’s travel illustrations similarly encapsulate the perils of hypermobile, navel-gazing perspectives. In Retard (tsa) (2018), Huang storyboarded a tale of mutual frustration during an encounter with a TSA officer; her wide-eyed, nostril-flaring portrait bordering on caricature. It is a striking example of the indignation of entitled cosmopolitanism that mistakes itself for radical critique. Subjects like the Black adversary of her comic are produced by histories of forced displacement that often leave people with little choice but to become mere apparatus of the states that have dispossessed them—stakes much higher than Huang's regime of work trips and weekenders. Yet rather than revealing injustices in the realm of global mobility, Huang’s work is a crass reformulation of the same biases and failures of solidarity that allow for them. It was a weak gesture at pot-shotting the Man.

Elsewhere, in Yee I-Lann’s film Tikar Reben (2020), a group of women wade into the water surrounding their homes. As they cross the shallows toward a clutch of stilt houses, home to the stateless peoples of Omadal Island, Malaysia, they unfurl and carry a vibrant woven ribbon. Through dedication to the practice of weaving, Yee champions not only a mode of gathering community but a lifeblood for it—a business model stewarded by women. As an artwork, Yee’s project may inadvertently impose a Google-mapification of this space that has traditionally operated with disregard for the logic of nationhood and boundaries, drone-like, as it charts a procession toward home. As a project, it highlights the still enduring potential for self-determination that persists in spaces that defy the logics of state that dictate the terms of contemporary movement. Their journey across the water is a joy, and here it refocused the political stakes of place that are, at times, obscured in the haze.