Shows

Hung Liu’s “Pulse, 1989–1996”

Hung Liu

Pulse, 1989–1996

Ryan Lee Gallery

New York

April 30–June 22, 2024

Before Hung Liu (1948–2021) moved from China to the United States to study at the University of California San Diego, the late artist starred in a weekly TV show called “How to Draw and Paint.” Trained in mural painting at Beijing’s Central Academy of Fine Arts, Liu offered guidance on painting techniques in the socialist realist style. The show was popular, and she “became a sort of television celebrity,” according to her widower Jeff Kelley, whose biographical essay was on view at Ryan Lee Gallery’s showcase of her works “Pulse, 1989–1996” in New York. The posthumous exhibition demonstrated how Liu, who had experienced notoriety herself, effectively imbued images of social, cultural, and political myths with palpable, personal subjectivity.

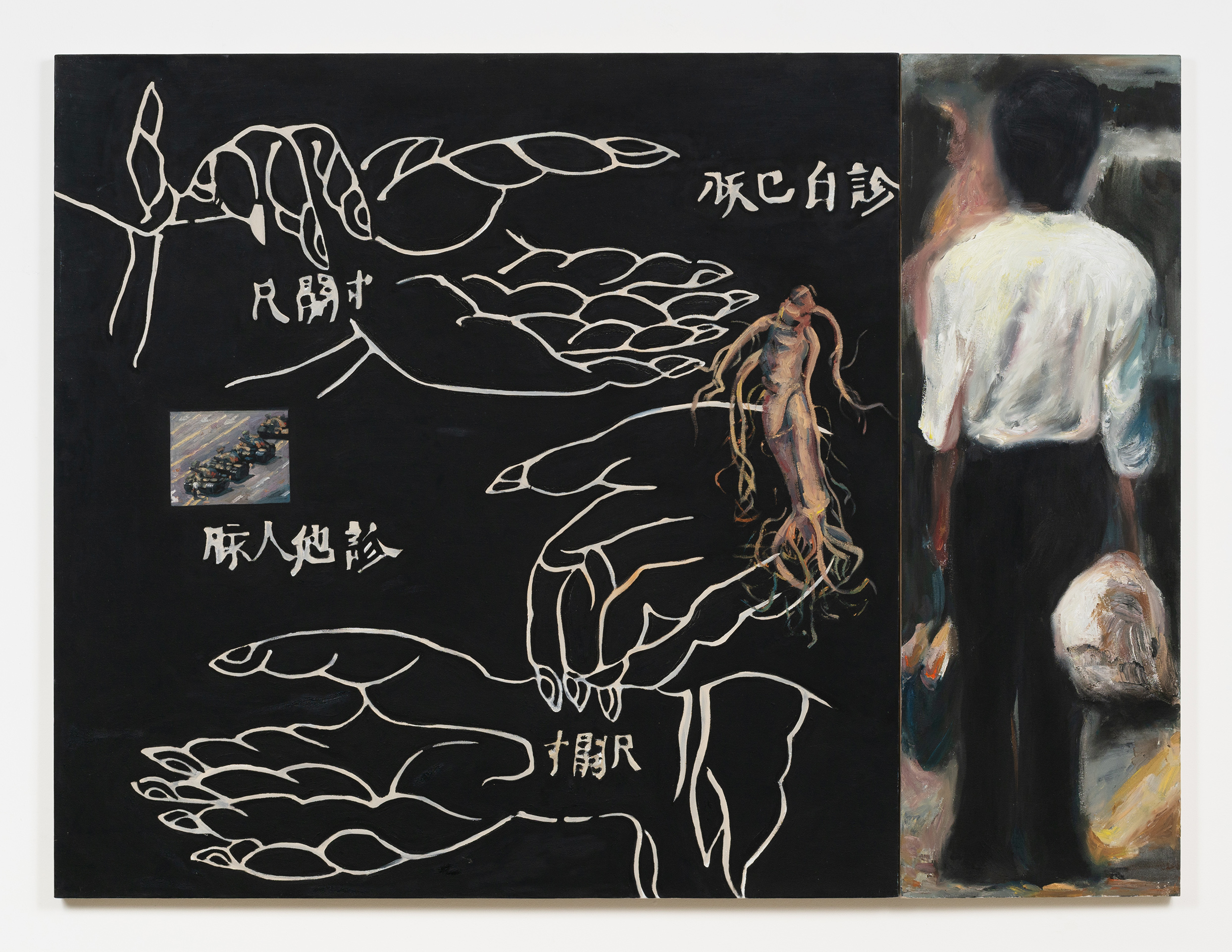

By showing Liu’s works created between 1989 and 1996, in the wake of the Tiananmen Square demonstrations and subsequent suppression, “Pulse” contended with the making and mass dissemination of images that represent iconic moments. Throughout, Liu poetically processes the “June Fourth Incident” in a blend of representational figuration, abstraction, and assemblage. For instance, the titular two-panel painting Pulse (1990) manipulates Jeff Widener’s notorious photograph of the crackdown at Tiananmen Square, Tank Man (1989), which was taken one kilometer away from the scene, by juxtaposing Liu’s synchronous distance from the tragedy. The painting’s larger left panel is engulfed almost entirely in black, and a reproduction of Widener’s photograph was painted in the middle far left, with four human hands traced in sinewy white lines dominating this panel, referencing ancient medical illustrations instructing how to check a pulse. Chinese characters and a ginseng root punctuate the hands enigmatically. Together, this combination of imagery suggests the complex humanity and bravery that the otherwise anonymous “Tank man” evinced when he stood before the vehicles. A close-up of the man occupies the entire thin right panel, but Liu nevertheless renders him in swaths of blurry brushwork in muted tones. Unlike the attentive strokes of the four hands, Liu depicts the man almost abstractly, as if illustrating our inability to regard the pain of others. Kelley writes in his essay that Liu knew Tiananmen Square well by participating in public mourning and protests there in 1976; watching events unfold 13 years later from her home in Texas, she could only imagine what her compatriots were experiencing from a distance.

Liu’s convergence of the tenets of traditional portraiture, formalism, and icons or symbols appears again in Chinese Pieta (1989), installed directly opposite from Pulse. An early example of portraiture on shaped wooden panels, Chinese Pieta comprises a flattened, ink-drawn replica of Michelangelo’s La Pietà (1498–99) against an outline of China’s borders and a black rendering of the Forbidden City, both painted directly on the wall. This mix of European and Asian symbols, dimensionality, and portraiture comes from a larger installation, Trauma (1989), in which Liu symbolically confronts Tiananmen Square. Its composition is similar to Pulse, but this time Liu features a historical map of the Forbidden City on top of a diagram of Chinese acupuncture points, and a character from the Revolutionary Opera film Shajiabang (1971) on the thin right panel. This feels experimental, as if Liu urgently needed to process her feelings about the incident and post-Revolutionary China at large.

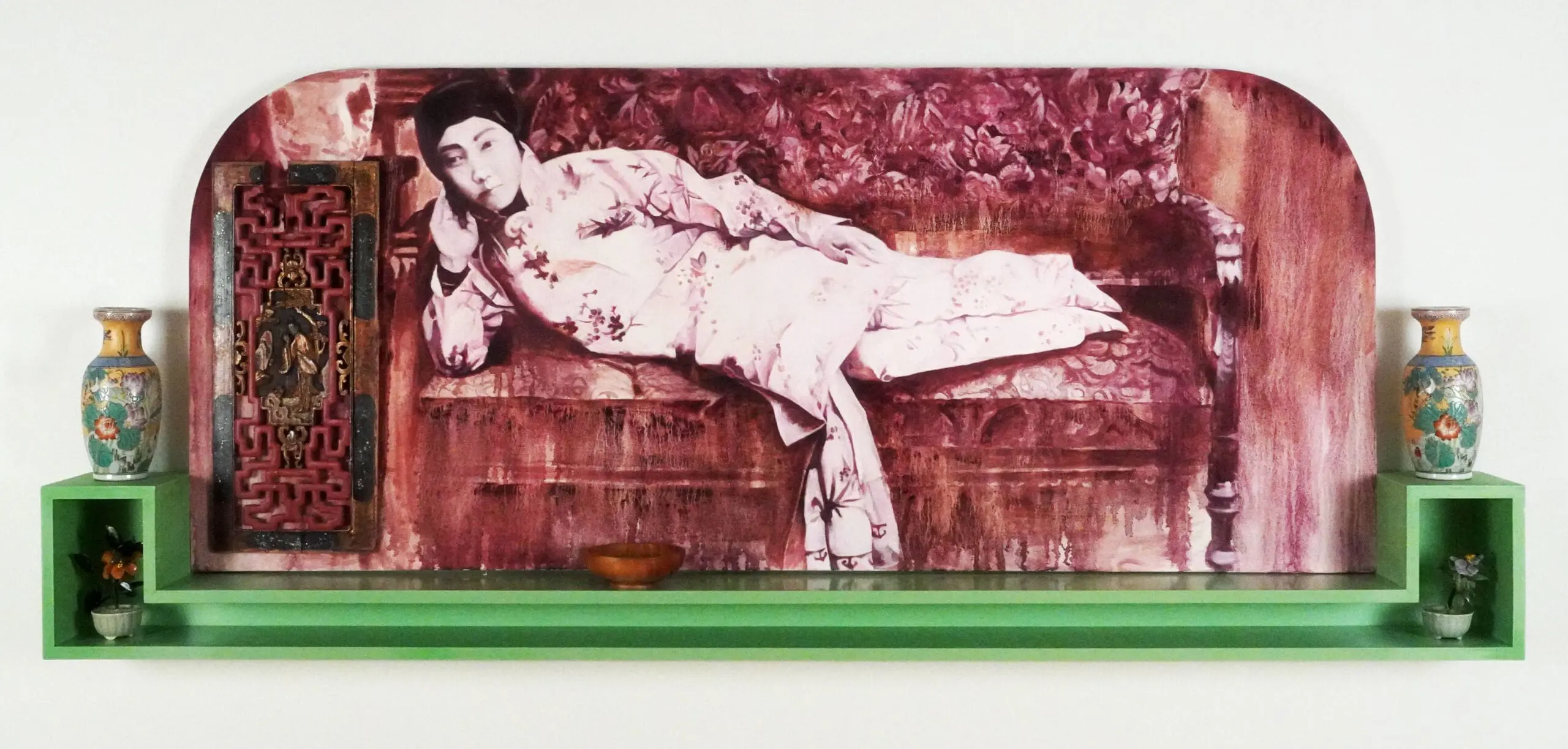

The first room in this exhibition included several examples of Liu’s more careful, sophisticated, and ardently empathetic combinations of Asian and European references, expressionistic portraiture, and documentary impulse. In that regard, her larger-than-life portraits of anonymous Chinese women as courtesans, sex workers, or actresses, all based on archival photographs, were particularly evocative. Olympia II (1992), for instance, depicts a 19th-century Chinese sex worker as an odalisque (a female attendant in the Ottoman royal court, and a symbol loaded with orientalist gaze) framed with traditional Chinese ornaments and a bright green shelf with plants on either side. Liu likewise mixes objects, such as a junk-shaped woodblock and Chinese bird cages, with painting in Migrants (1993) and Boxer Rebellion I (1996), respectively. In both, Liu manipulates the portrait-making impulse with a postmodern painterly assemblage, remixing documentary records with personhood.

“Pulse” demonstrated Liu’s typical sensitivity toward her subject matter. But the intimate scale of many of these works, which included paintings on dimensionally shaped canvases and multimedia assemblages, wherein the artist simultaneously deconstructs and reconstructs iconic imagery, permeated the exhibition with tenderness. As with much of her practice, in these works Liu amplified pictures of people, who, despite being anonymous with grand historical narratives, have shaped our contemporary world.