Shows

Huma Bhabha: “Facing Giants”

For her sixth solo show at Salon 94, Pakistani-born, New York-based artist Huma Bhabha continued to experiment with the classic statuary tradition, emptying and expanding it to include a wide variety of visual resonances rooted in sources ranging from German expressionism, Cubism, and Greek kouroi to horror and science fiction. This recent exhibition, “Facing Giants,” consisted of around a dozen works on paper and two groups of sculptures, including the totemic figures for which Bhabha is best known and another set of battered, curiously disfigured sculptural busts.

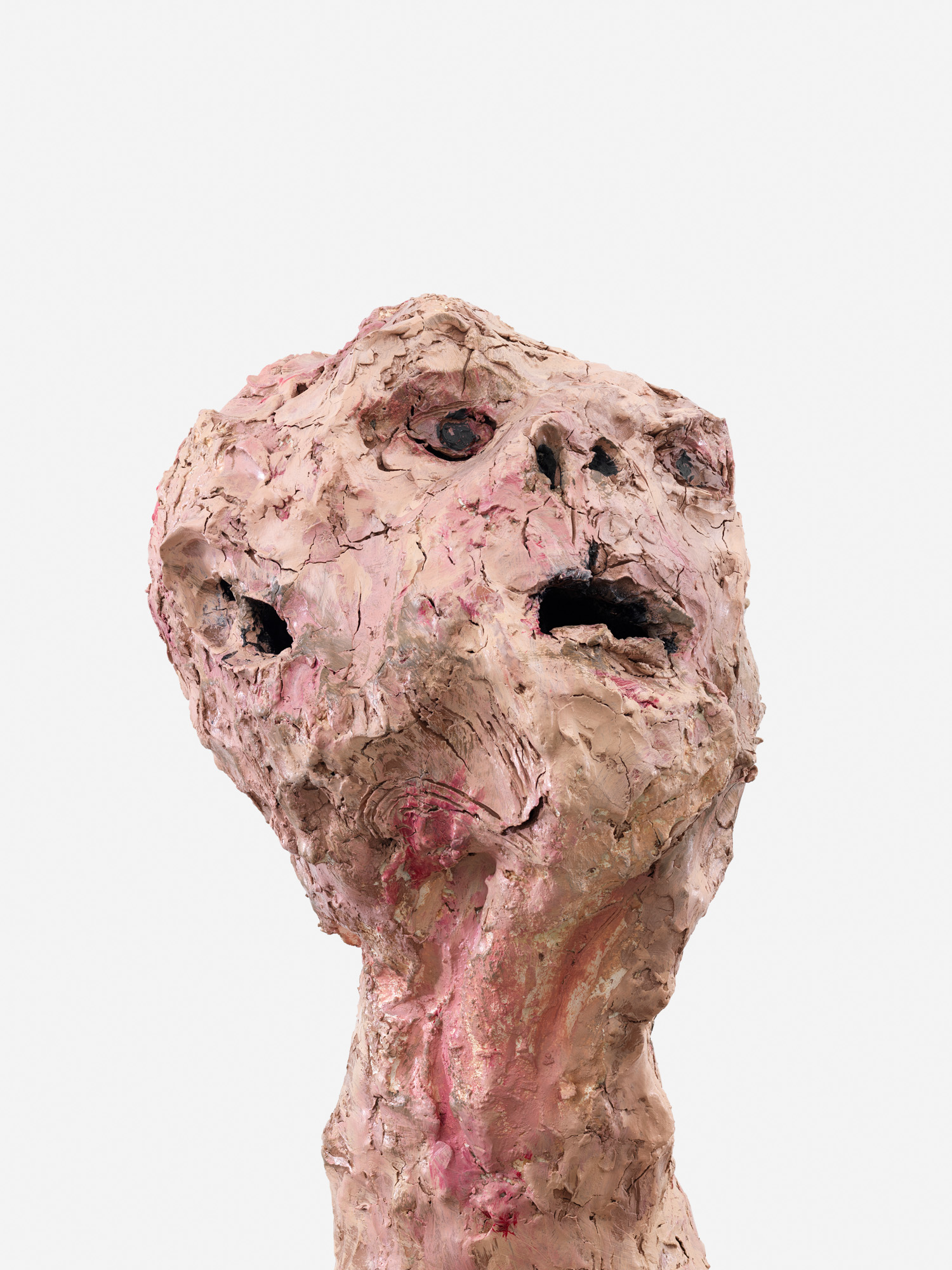

The more intriguing development in her recent artistic output is exemplified by the latter sculptures, which pulsate with visceral material presence. For example, using wood, plaster, clay, wire, and acrylic, Bhabha created a pink molten bust, Listen to What I’m Not Saying (2021), that looks as if it is caught in physical agony, or in the middle of a painful process of being kneaded and formed into existence. The work evinces an intense, almost violent, haptic immediacy: curdled forms, asymmetrical mounds of plaster, chaotic incisions, a gaping mouth.

In his book The Sculptural Imagination (2000), art historian Alex Potts argues for how sculpture engages us kinesthetically, not just with a disembodied gaze. Because of its three-dimensionality, he contends, a sculptural body cannot be apprehended all at once and is thus subject to a kind of physically roving, fragmented viewing that allows sculpture’s supposedly inert, fixed form to come alive. Such a theory of sculpture animates works like Listen to What I’m Not Saying, which requires full circumambulation as each side offers a different revelation. When viewed from the back, a large orifice emerges into view, ensconcing tangled wires and allowing us a literal peek into the inner workings of this lobotomized, uncanny figure. Similarly, another sculptural bust entitled The Ancient and Arcane (2021), made of patinated bronze and with hollowed out eyes recalling Douglas Gordon’s haunting, eye-less photographic portraits, features a sizable, almost grotesque hole in the back of its head, as if someone had pried it open with their hands.

These sculptural busts look as if they were petrified in the middle of transmutation, thus remaining forever entropic yet exempt from any concrete sense of time or place. If monsters, in the loosest sense of the word, serve as cultural metaphors for larger anxieties around deviance and difference, Bhabha’s figures, which manifest the slightest, most tenuous human-like qualities but override these very qualities with their otherworldly monstrosity, dramatize fraught questions of what counts as normative embodiment. This particular group of sculptures in the show vibrates between Giacomettian alienation, soft abjection, and the thrashing expressionism of painters like Georg Baselitz.

The other group of sculptures in the show evoke votive, totemic figures, the kind that Bhabha has been sculpting since the 1990s and which serve as a unifying thread through her various solo exhibitions over the years. Her practice is deeply informed by Northwest Coast and African totems, and she often incorporates unorthodox, mundane materials in these sculptures. In the modestly scaled Pathfinder (2021), the skeleton of a horseshoe crab comprises the head of a vaguely human body, its tail sticking up like an antenna. The body, chiseled from dark brown cork, is marked by deep crevices, and its blocky form recalls the rigid poses of ancient Egyptian funerary statues. It is difficult to ascertain what the horseshoe crab actually is at first glance; its ambiguous status as a once-living, enfleshed entity makes it both off-putting and fascinating. (Bhabha worked in a taxidermy studio in the early 2000s, and kept animal skulls they didn’t want.)

Much of the writing around Bhabha’s works have focused on their archaeological sensibility and exploration of primordial mythologies, but as the Frankensteined anatomy of Pathfinder suggests, perhaps an equally fruitful angle to examine Bhabha’s works is how they reconceptualize our inherited ideas of sculpture as a primarily representational medium. Can a horseshoe crab skeleton “represent” or stand in for a head? Rather than using sculpture as a mode of likeness, Bhabha knows how to abstract and retool sculpture to tap into our innermost reserves: an anxiety conferred by the melting, agonizing busts, or a surprising sublimity that arises from craning our necks to look up at the tall, totemic characters that appear equal parts sacred and unnerving.

Huma Bhabha’s “Facing Giants” is on view at Salon 94, New York, until June 26, 2021.