Shows

Highlights from Aichi Triennale 2022

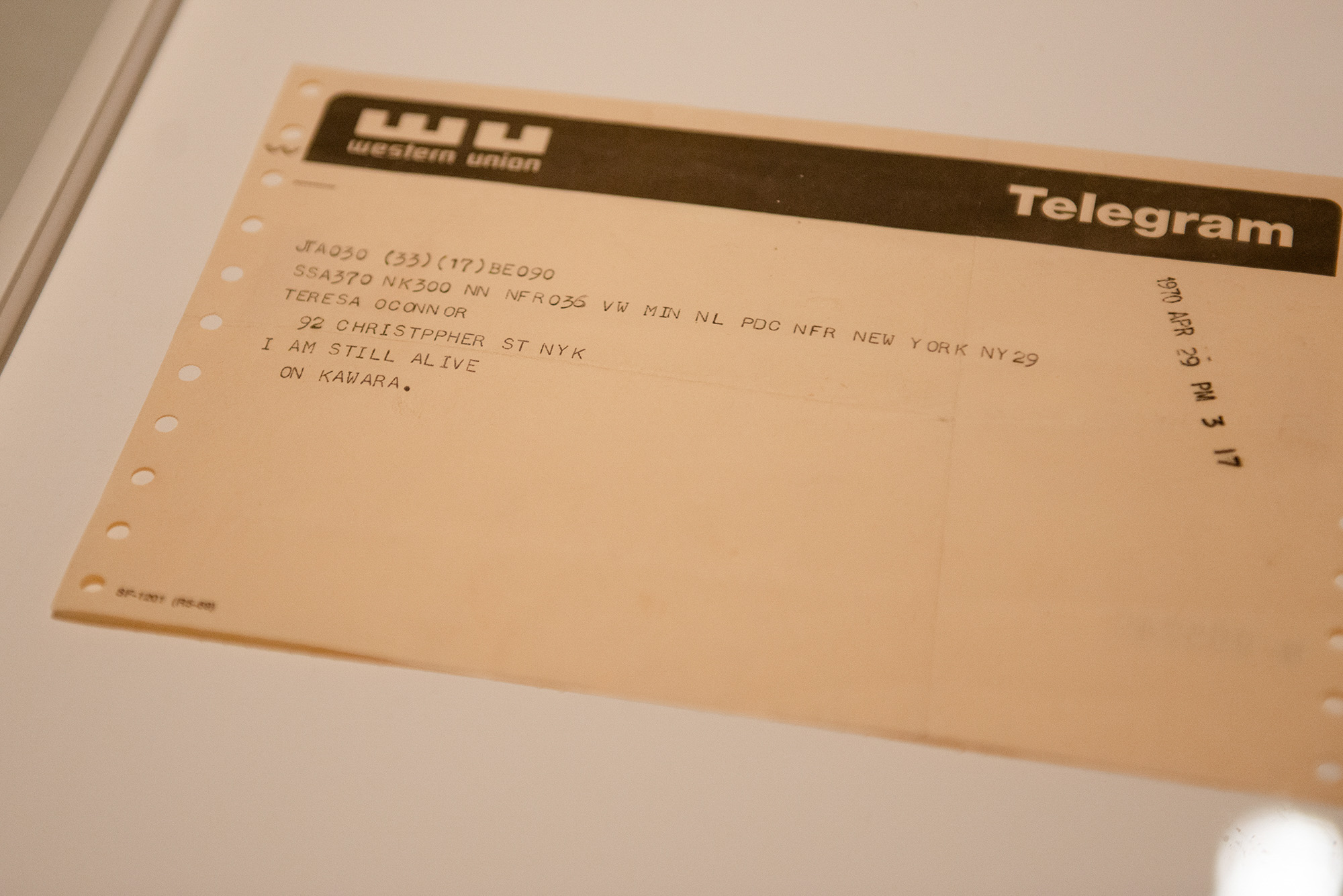

One of the largest urban international art festivals in Japan, Aichi Triennale 2022 took place at a number of venues across the Aichi Prefecture including the Aichi Arts Center in Nagoya and renovated industrial or commercial buildings in Ichinomiya and Tokoname. A total of 82 artists, 11 performance art groups, and seven artist-led educational groups participated in the festival. The theme this year, “Still Alive,” is derived from a series of works by Aichi-born conceptual artist On Kawara, who continually sent telegrams with a single message “I Am Still Alive” to his friends all over the world from 1970 to 2000, as an acknowledgement and evidence of his own existence.

Mami Kataoka, artistic director of the Triennale and the director of Tokyo’s Mori Art Museum, explained that the theme should be interpreted from multiple perspectives during this period of turbulence. At the press preview, she said, “We hope that the visitors not only enjoy contemporary art, but also dig into the local history in Aichi and enjoy the artistic dialogue between Japan and other parts of the world . . . We are convinced that all visitors, after visiting all venues, could feel the force of art that helps us survive this period of difficulty.”

Following the controversy over censorship brought by the special exhibition, “After ‘Freedom of Expression’?” in 2019, the Aichi Triennale Organizing Committee has undergone a reform. The Triennale managed to continue, but due to the travel restrictions amid the pandemic crisis, many were concerned that the scale of the show would be shrunken. As a result, Kataoka aimed to create a new form of international art festival that is timely and appropriate. Since the curators couldn’t conduct research abroad, the Committee selected nine curatorial advisers globally to recommend artists who would be able to respond to the theme “Still Alive.” Here are some highlights across the venues in Nagoya, Arimatsu, Ichinomiya, and Tokoname.

AICHI ARTS CENTER

At the Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art in central Nagoya, the exhibition began with On Kawara’s telegrams, which were showcased in a vitrine. The telegrams were gathered from his recipients around the world for this special occasion. Collectively, these telegrams demonstrate Kawara’s life experiences as a record of existence throughout the years.

Similarly exploring the sense of survival, for Event Horizon, Slovak conceptual artist Roman Ondak sliced the trunk of an oak tree into 100 disks. On each disk, he stamped the text of a historical event from 1917 to 2016 onto its corresponding annual ring. The staff hung one disk onto the wall each day throughout the festival until the whole wall is covered. The performance-based work suggests the link between natural and human history, and reflects on people’s change of perspectives on history as information accumulates every day.

The 1969 exhibition “557,087” curated by Lucy R. Lippard in Seattle was considered as the first institutional conceptual art show, since the participants did not visit the venue in person but sent their instructions to the museum staff for execution. At the Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art, Yuki Okumura reproduced 30 works from “557,087” to reinterpret the methodology adopted by the conceptual artists in the 1960s–70s and to achieve a “self-other unity” under today’s context. Using his own body as the agent of action, he created these objects based on his own mental, physical, relational, and situational conditions as the parameters for specification.

Elsewhere at the Museum, the curatorial team also organized educational programs based on the idea of “art for everyone.” The team presented the results from the program “Clan Research” last summer, led by artists Takayuki Yamamoto and Shōjō Collective, which searched for life-size dolls called Shōjō (the red-face dolls seen in the middle of the photo above) at local festivals in the southern part of Aichi Prefecture.

ARIMATSU

Arimatsu in Nagoya City is known for its traditional tie-dye fabric Arimatsu-Narumi Shibori, which has more than 400 years of history. Nine artists exhibited at six venues and eight sites along the ancient Tokaido Road, with works focusing mainly on textile.

In a former kimono shop, Malaysian artist Yee I-Lann’s Tikar Reben was suspended from the ceiling like colored ribbons of festival decorations, with the unrolled coil displayed on a white pedestal. Tikar as a woven mat is usually placed on the floor, but at the kimono shop, it evokes obi, the kimono belt in Japanese culture. The accompanying video documents the rolling out of a 54-meter-long tikar between the Malaysian Omadal Island and the stateless Bajau Sama DiLaut weavers’ water village.

Inspired by Arimatsu’s townscape, where tie-dye fabric usually hangs outside of houses and shops, Thai artist Mit Jai Inn installed People’s Wall, a painting on canvas in the form of ribbon, in front of eight sites along the ancient Tokaido Road that once connected Edo with Kyoto. The installation modestly changed a traditional street view.

In the traditional tie-dyeing practice of Arimatsu-Narumi Shibori, the cloth is sewn and tightened with threads to create empty areas that will not take on the colors, before dipping it into the dye to generate a variety of patterns. For Aki Inomata, Arimatsu-Narumi Shibori resembles the bagworm’s protective case, which is often interweaved colorfully with materials collected by the worm from its surrounding. In an acrylic box, she provided the bagworm with some tie-dyed cloth and “commissioned” them to create colorful bags.

ICHINOMIYA

Ichinomiya City is famous for the Masumida Shrine located in the center of the town. Here, the concept “Still Alive” is channeled by contemplations on the related themes of prayer, mental health, or life and death. Nineteen artists showed their works across ten venues.

Anne Imhof’s new video was displayed on multiple screens at the former Ichinomiya City Ice Skate Rink, which once witnessed the growth of Japan’s Olympic-team skaters. Projected in a fantasy-like atmosphere, Imhof’s video features choreography by young dancers with reactions from the audience, highlighting the shared anxiety and performativity faced by both performers and athletes.

Before studying abroad in Germany, Yoshitomo Nara obtained his master’s degree from the Aichi University of the Arts. At Orinasu Ichinomiya, his sculpture Fountain of Life (2001/22) features seven heads of his signature child-like figures in a huge teacup, with tears running down the children’s faces. Their tears, whether of joy or sadness, generate a pool of water in the cup as a source of life. In the same building, he also presented six paintings and drawings in a setting that recalls a prayer room.

Ichinomiya is traditionally a textile town, known for its mass production of woolen fabric. Based on her research of the history on the relationship between people and sheep, Kaori Endo dismembered a sheep, spun and weaved the wool into a large-scale parachute, hovering above the looms and household items at the Toyoshima Memorial Museum. While the work highlights the town’s past glory, it stimulates critical reflections on animal cruelty in a historically renowned industry.

Chiharu Shiota’s newly commissioned work Following the Line (2022) filled the two rooms of Nokogiri2, a defunct woolen textile factory that has been transformed into a gallery. Her signature red yarn threads, connecting the disused woolen machines and yarn spool holders at the site, evoke capillaries in the body and revive memories of the various lives dedicated to the local industry.

TOKONAME

In Tokoname City, known for its pottery, 12 artists presented their works at six venues. As pottery incorporates the force and blessing from the natural elements of earth, fire, and air, the works here investigated the industrial history of the city and the complex relationships between art and craft, human and nature.

At Maruni-Toukan, a former earthenware pipe factory, the floor was blanketed by an enormous amount of cookies and rice cakes made with clay from Tokoname. Delcy Morelos connected the local soil with a ritual from the Andes Mountains, where people thank the earth goddess Pachamama by burying cookies in the ground. While their shapes look simple, the installation, covered by spice, stimulates the sense of smell and touch experienced in both the ritual of baking and firing clay.

Kenichi Obana’s drawings and sculptures weave together stories of the “Ichijiku (fig) man,” the owner of a traditional teapot store. After closing the store, the owner started growing figs in the farm behind the store. Obana’s works originated from his research and conversations with the “Ichijiku man.” As an attempt to universalize individual experiences, Obana’s visual manifestations of the stories blend together oral narratives and history, fiction and reality.

Growing up in Argentina, Florencia Sadir’s practice often derives from her friendship and collaboration with others. Visualizing humanity’s connection with nature, her work Rain of Mud, spanned the space at a former pottery factory like a huge curtain. The installation comprises 12,000 ceramic balls created in collaboration with local ceramic artist Katsuo Mizukami—whom she befriended during her time in Tokoname—as well as other young ceramicists.

%20-%20Kizuki-au.jpg)

“Kizuki-Au—Collaborative Constructions,” one of the collaborative programs at a former pottery house, showcased two installations made of wood and pottery through digital fabrication. The gate of the house, created by T_ADS Obuchi Lab from the University of Tokyo, consists of chains of ceramic pieces from Tokoname. The three-story-tall timber-frame structure in the courtyard is inspired by chimneys in Tokoname and built by Gramazio Kohler Research from ETH Zurich, which reinterprets traditional Japanese carpentry through the Robotic Fabrication Lab at ETH. Corresponding to “Still Alive,” the structure proposes a possible, sustainable alternative to concrete and steel constructions.

Aichi Triennale 2022, “Still Alive,” is on view at multiple venues in the Aichi Prefecture until October 10, 2022.