Shows

Hassan Khan’s “Blind Ambition”

%20Centre%20Pompidou_he%CC%81le%CC%80ne%20Mauri%20(3).jpg)

%20Centre%20Pompidou_he%CC%81le%CC%80ne%20Mauri%20(3).jpg)

A giant stuffed pig with a creepy grin; an ever-evolving hip-hop song dictated by an algorithm; the aspirations and demises of various characters living in Egypt: these are some of the impressions retained from a visit to Hassan Khan’s solo exhibition at Centre Pompidou. Titled “Blind Ambition,” Khan’s first major institutional presentation in France gathered 36 artworks from the past 20 years.

Informed by Khan’s double practice as a visual artist and a musician, the exhibition’s scenography was theatrical, with a wooden stage marked by podiums of varying levels occupying most of the room. Accessible through ramps, the platforms brought together works created years apart with little formal resemblance, thus creating heterogenous groups of sculptures, prints, and videos. The visitor was not guided by a chronological nor thematic trajectory, but rather was invited to wander in a space shaped by visual and sonic associations, contrasts, and “remixes” of artworks in Khan’s words, with several installations having been reformulated for this context.

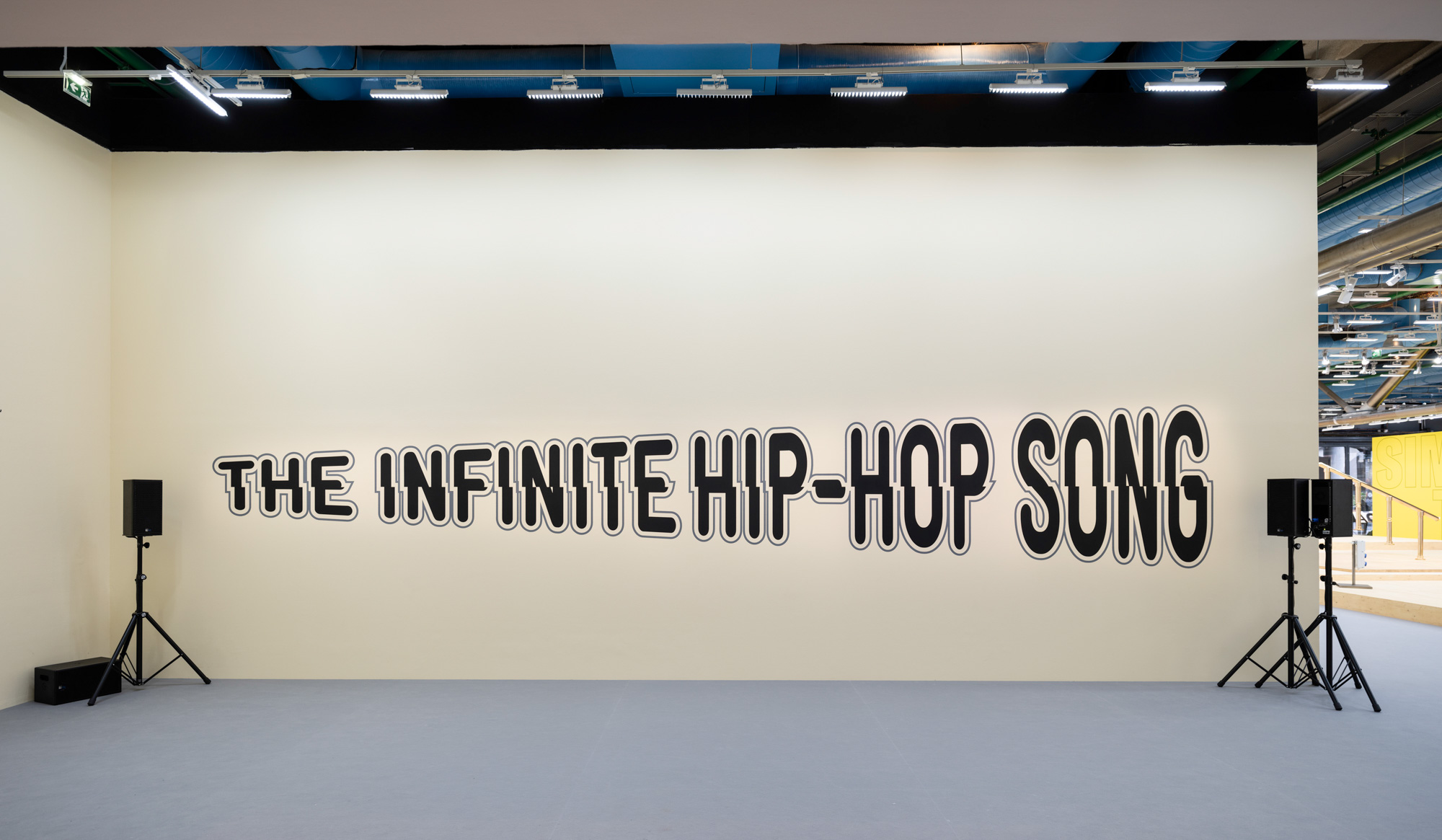

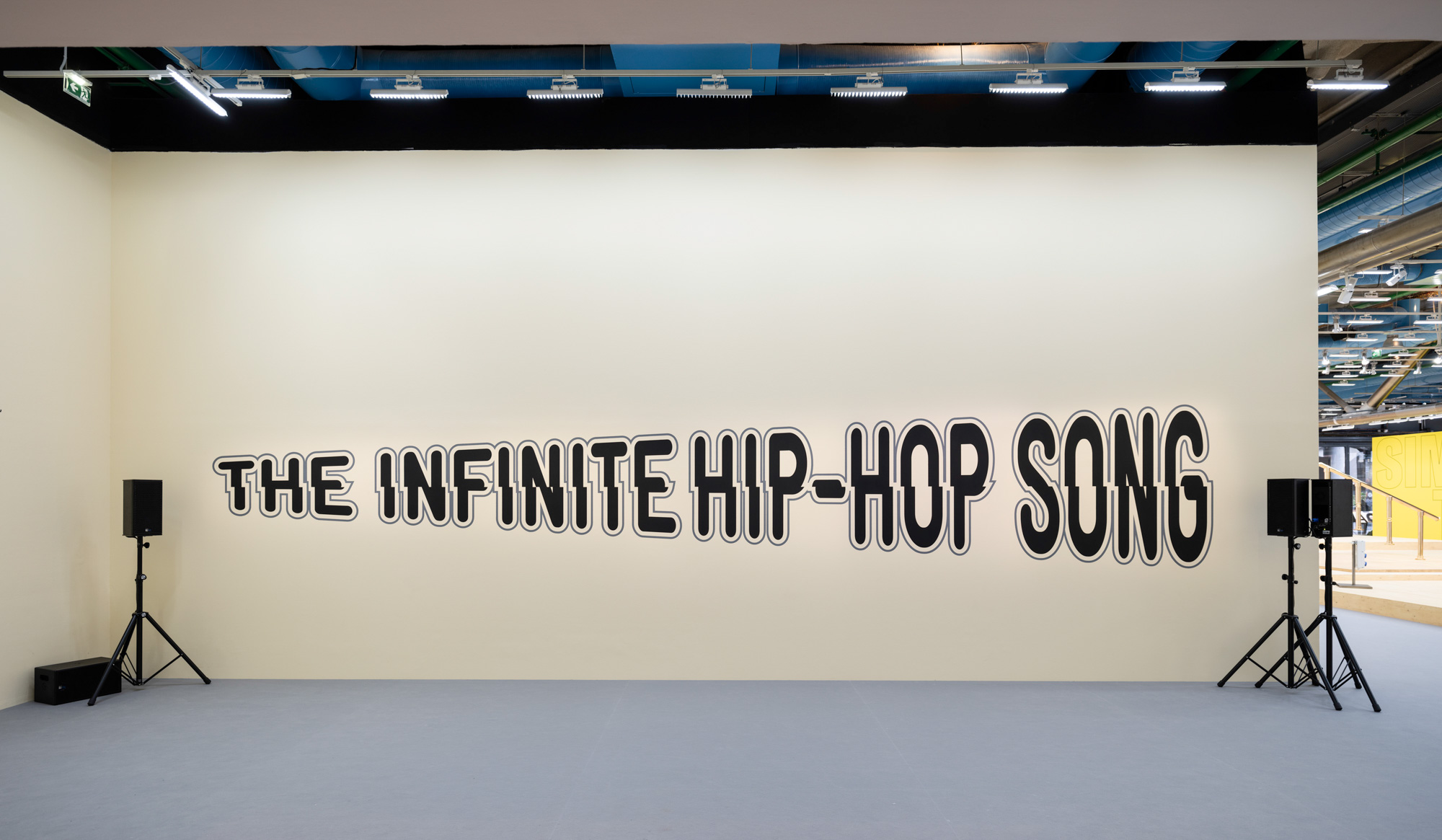

At the exhibition’s entrance, a small iteration of The Infinite Hip-Hop Song (wall version) (2019) stood apart from the stage. Four speakers blasted combinations of hundreds of compositions and ten songs written in English by Khan. The music was the result of a layered process: 11 rappers had been guided by Khan to perform the songs, and their recordings were combined with the melodies through an algorithm, thus producing myriads of tracks. The rappers’ individual flows clash with and resist the homogenizing effect of computerized production. Moreover, with the combinations constantly renewed and the songs played continuously, no track could be heard twice. Remarkably gripping, the installation set the tone for the exhibition: it introduced Khan’s inclination toward collaboration, his obsessive engagement with automation, and his use of popular music to highlight the potential of (sub)cultures to counter hegemonic modes of production.

%20Centre%20Pompidou_he%CC%81le%CC%80ne%20Mauri%20(18).jpg)

In a room at the opposing end of the gallery was the installation DOM-TAK-TAK-DOM-TAK (2005). It centered on shaabi music: literally meaning “of the people” and originating from the streets of 1970s Egypt, this genre features the piercing double reed (mizmar) and the rhythmic goblet drum (darbuka). In an effort to deconstruct shaabi, Khan led individual studio sessions with six musicians, each improvising on an instrument, before combining the results against standard percussion recordings to produce new compositions. Titled after the darbuka’s distinctive smack and marked by the rhythm of a metronome and blinking lights, the work associates the spontaneity of improvisation with the intentionality of studio-recording. In contrast with The Infinite Hip-Hop Song where Khan forsakes decision-making in favor of an algorithm, here, he assumes the position of the orchestrator.

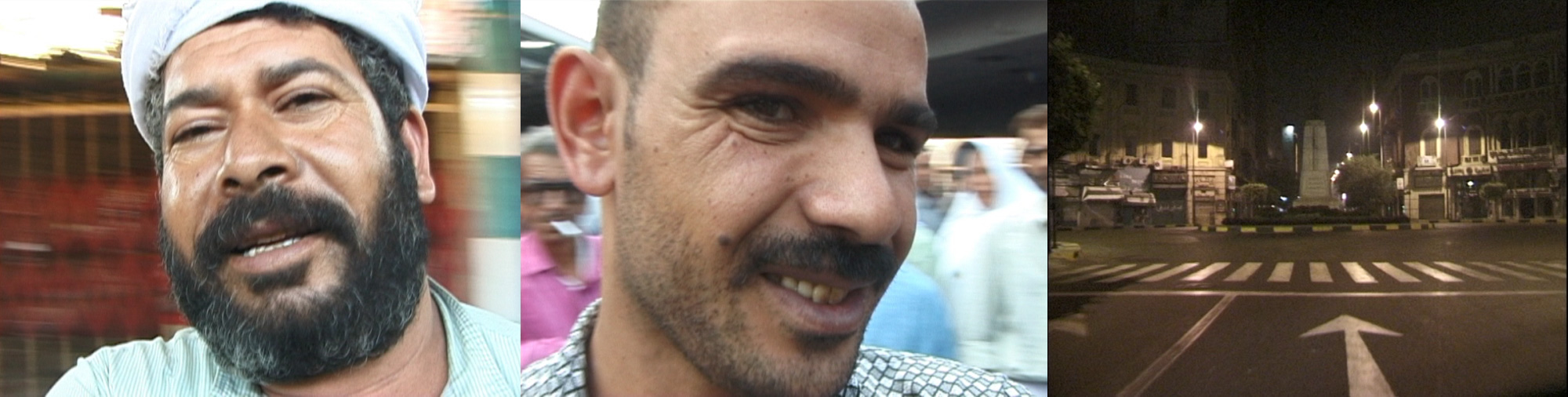

A similar methodology is used when Khan collaborates with actors: he alternates between giving them scores and letting them lead the way. Comprised of 16 narratives recounted on four screens, The Hidden Location (2004) plays on actors’ interpretations of stories unfolding in Egypt. We listen to a smart aleck dissect the bourgeois aspirations of a certain Mo, then follow a couple’s spat during a walk around the city. The installation owes as much to urban anthropology as to the sociological analysis underlying Egyptian drama series.

But Khan’s ambiguous relationship with his own agency is most palpable in Transmission (2002), a three-channel video installation made using a MiniDV camera that he gave to three people. Each one shot themselves spiraling around Cairo’s empty streets at night, simultaneously creating a portrait of themselves and the city. Placed at eye-level against the gallery’s glass panels, Transmission created an uncanny dialogue with Paris’ bustling district of Châtelet.

Other works embedded within the gallery’s windows were visible from the outside, including aluminum panels explaining “the police function” (Purity Machine, 2021), and cushions shaped like cartoonish eyes resting on a glass plinth (W, 2021). This display ironically exposed the commodification of grotesque, systemic violence in late capitalism.

In an exhibition that avoided didacticism and surveyed a practice characterized by formal dissonance, the visitor often felt as if grappling with a riddle. In fact, what ties Khan’s practice together is his methodology: a simultaneous inquiry in and escape from the homogenizing forces of contemporary society.

Hassan Khan’s “Blind Ambition” was on view at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, from February 23 to April 25, 2022.