Shows

Guan Xiao’s “Flattened Metal”

The Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, in association with the Hong Kong-based K11 Art Foundation is presenting Chinese video artist and sculptor Guan Xiao’s first solo institutional exhibition in the United Kingdom. “Flattened Metal” attempts to search for a new visual language, one that is universalized and transcultural, while commenting on the permeation of information technology in modern life.

Guan’s work combines media—sculptures, found objects, screens and video—to produce odd and unseemly juxtapositions. By analyzing the relationship between the past, present and future, she looks at ways temporality plays into our ideas of perception. Her incomprehension of time, begins with the inability to fathom the past, apprehend the present or foresee the future; she thereby uses her unique hybridized assemblages to derive context and meaning through their subjective associations with one another.

It is within the element of artificial historicity that Guan’s works find impetus. Her sculptures serve as a pastiche—mimicking historical artifacts, using new-age materials to make new objects appear old. By incongruously combining unrelated objects, she creates a discourse that brings together the unexpected, in order to find new prospects of meaning.

“Flattened Metal” includes five, newly created mixed-media installations; each are composed of a mesh photographic backdrop, in front of which is displayed a collection of sculptures and found objects. The confluence of objects conflates history to create a dialogue between time periods. For instance, in one such work, Amazon Gold (2016), a replica of a 7th- to 10th-century Amazonian bird head—remade using resin, fiberglass and plastic—sits atop a mock scepter handle derived from the Classic Maya period (c. 250–900 AD). These two pieces, sourced from antiquity, interact with a Fox Instinct motor-race boot, to form a strange composite entity that does not recall any generation.

This anachronistic relationship between the objects exists in most of the works. In Little Drum (2016), a modern-day table lamp perches on the re-creation of a colossus right foot from the 4th century BC. In antiquity, large-scale statues were reserved for gods and kings; hence, this foot is presumably part of a larger Greek statue of an Olympian god. The juxtaposition of a deity’s foot with something as commonplace and mundane as a lamp, prompts viewers to consider its meaning and the varied approaches of understanding the world.

A delicate balance between visual and audio elements is constantly struck in Guan’s works—two senses the artist believes are heightened due to continuous technological stimulus. In From Unit 3 to Unit 7 (2016), two large speakers support the weighty blue resin tabletop. The speakers emitting sound stands next to a re-creation of an Aztec sculpture head from the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico. This head sits immobile on a tripod. The work is suspended between different eras—neofuturism meets primordiality— providing possibilities for existence. The screen behind it displays, “Is this outfit more Mary or Martha? Miranda. Thank you for watching.” The message explores the linguistic incongruity, where the meaning and mode of speech are in discordance with one another.

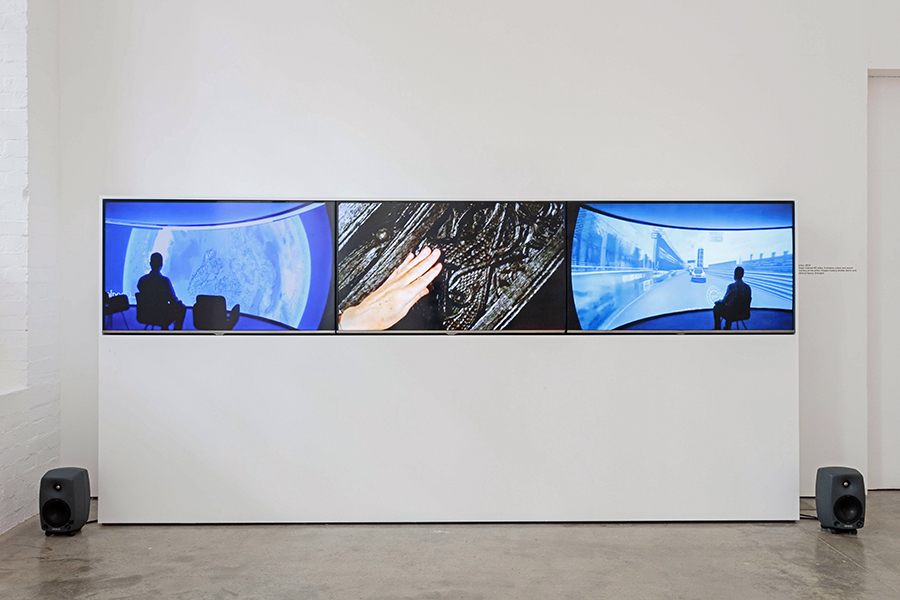

With the internet becoming our primary source of information, the artist is able to appropriate content from a diverse range of online material such as home movies, advertisements and promotional videos. In her video triptych Action (2014), the artist integrates sound, text and images to produce an eloquent visual journey. The three screens display a rhythmic compatibility: for instance, on one screen, pages of a book turn, causing a girl’s hair to fly in the wind in the other screen. In the central screen, text would display her inner musings, flashing statements such as “everything meets constantly . . . in the frequency of the universe,” alluding to the interconnectedness of the world. Stripping the images from their original contexts, Guan reframes them with a lyrical aesthetic. In an interview with curator Nav Haq, the artist, concurring with this notion, explains: “For me, rhythm means all the intersections of sense. It’s a way I understand the associations between things. It helps me to try and transfer action, see listen, think about interactions and freely build a link between them.”

Guan is indeed masterful in her associations. She manages to affix the past, present, and future along with the visual and the aural. While understanding the importance of the internet, she steers clear of using it as a subject, and instead uses it as a tool to derive multiple possibilities of meaning.