Shows

Gravity’s Rainbow: Nie Shiwei and Wang Lei

Gravity’s Rainbow: Nie Shiwei and Wang Lei

Loft 8 Galerie

Vienna

Mar 8–23, 2024

With spring slowly emerging from its winter slumber, the streets of Vienna were awash in color, and so too was Vienna’s Loft 8 Galerie, which presented “Gravity’s Rainbow: Nie Shiwei and Wang Lei.” Curated by Alexandra Grimmer, the exhibition of oil paintings, graphic works, ceramics, and sculptural objects and installations paired two Chinese artists—both of whom were born in the 1980s and based in Beijing. It also marked the fifth exhibition organized by Blue Mountain Contemporary Art (BMCA) for Loft 8. A private collection of contemporary Chinese art based in Vienna, BMCA was established in 2013, having moved its headquarters from Beijing to Europe. In addition to exhibitions, their work focuses on artist residencies and artistic collaborations between Chinese and European artists.

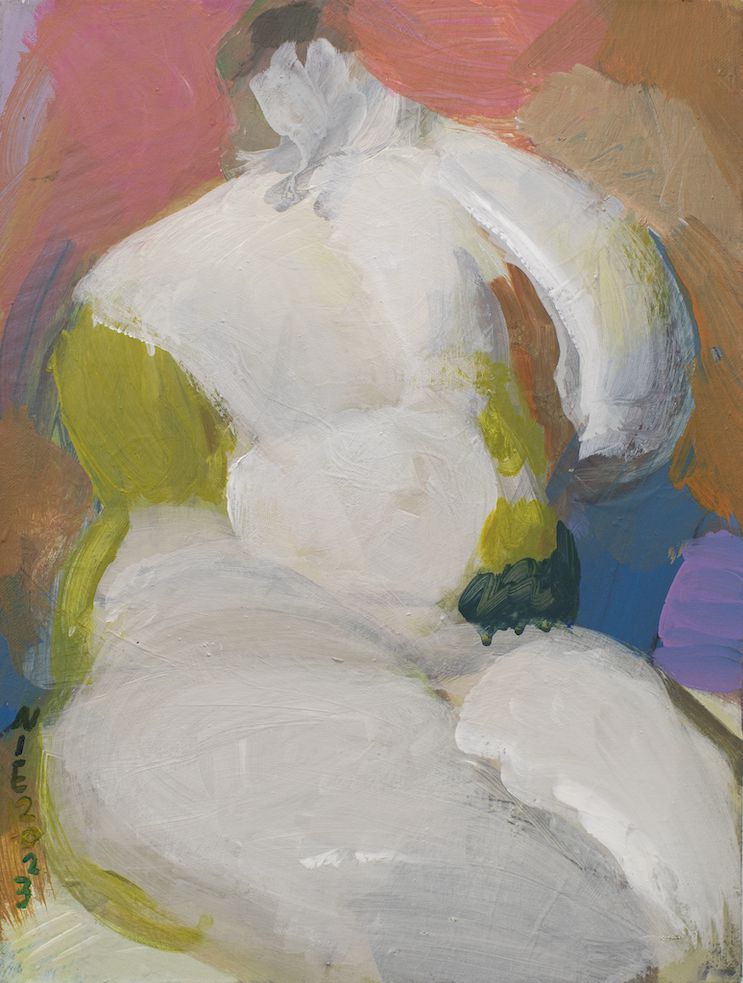

Born in Shandong, Nie Shiwei (聂世伟) primarily uses acrylic on canvas, and the works on display suggest the artist’s commitment to figurative painting, gestural brushwork, and a palette of earthy browns and yellows punctuated by vibrant pastels. Take, for instance, two works from 2023: The Fat Woman—which depicts a woman with a voluptuous figure, ghostly white skin, twisting torso, and downward gaze—appears surrounded by a penumbra of bold color (recalling the work of Alexej von Jawlensky), and The Way Travellers Are Viewed, an equally ghostly white figure viewed from behind, its arched back poised as if ready to sprint beyond the viewer’s gaze. If Nie Shiwei finds his aesthetic starting point in Italian Baroque painting (evidenced here by distorted bodily compositions that convey a sense of movement through a certain gestural suggestiveness) his use of complementary or contrasting primary and secondary colors to elicit emotional reactions is characteristically (neo)expressionist.

Originally from Wuwei, Anhui Province, Wang Lei (王垒) (not to be confused with Wang Lei 王雷) studied sculpture at Hangzhou’s China Academy of Art, graduating in 2016. His installations on display at Loft 8 incorporated colorful accents and a range of materials, from concrete, stainless steel, resin, and sorel cement to wood, aluminum, and rebar. In some cases, he begins his process with preliminary watercolor drawings on paper, four of which were included in the show. Immediately within the visitor’s field of vision upon entering the gallery was The First and Second Factories (2023), in which a repurposed wooden pallet—cut into two curvilinear pieces—provided a manufactured landscape atop which sat two miniature replicas of brick factories, with their singular smoke stacks, along with a simple dam and a rural Chinese house. Just as bricks were an essential link between China’s ancient past and its Mao-era modernization efforts during the second-half of the 20th century, the two factories serve as physical and figural constructions of the artist’s childhood memories—a temporal link to the vanishing past of his grandparents’ kilns.

In other works, such as Secret Farm (2024), Wang Lei draws on Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (1495–98), creating a wooden beam along which twelve cast aluminum poppies flank a central poppy on both sides. (Although China strictly prohibits their cultivation, poppies occasionally make their way into Chinese cuisine.) In Reshaping Landscapes No. 7 (2023), a cracked aquamarine Buddha’s head rests on a fissured concrete block with a deep channel that splits into two (the off-kilter head recalling the work of Zhang Huan), while Reshaping Landscape No. 3 (2022) displays a similar concrete block—here bisected in two by a polished green ball in the groove, with another on top, and a swallowed Chinese pagoda (its steeple and base barely protruding beyond the material). What are we to make of such Surrealistic scenes that allude to Western art and architecture, as well as contemporary Chinese politics, and its use of industrial materials?

Perhaps one path out of the labyrinth of interpretive possibilities can be found in the exhibition title, “Gravity’s Rainbow,” a reference to Thomas Pynchon’s eponymous 1973 novel that explores, among other things, the emotional resonances that (re)shape our lives. For Nie Shiwei, the interplay of figurative art and color hints at deeper layers of meaning, while Wang Lei’s sculptures seem to search for memories that lurk beneath the surface of consciousness. Or as Pynchon wrote in his novel, “There’s some kind of blind passage of energy, through us, some way of making connections we can’t understand.”

Brian Haman is editor-in-chief of The Shanghai Literary Review and a lecturer at the University of Vienna.