Shows

Gravity and Grace in Gregory Halpern’s “King, Queen, Knave”

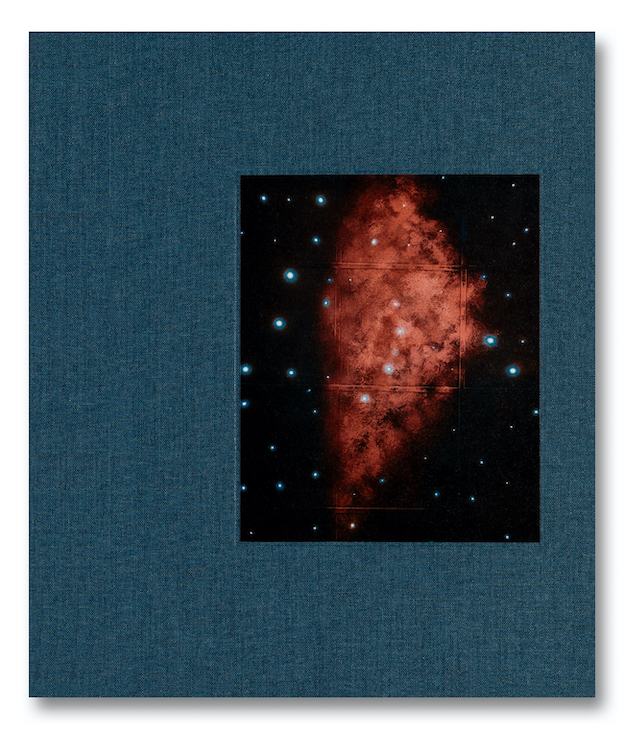

King, Queen, Knave

By Gregory Halpern

Published by Mack

London, 2024

Richard Serra, one of the 20th century’s great modernist sculptors, once remarked that artists who defer to context run the risk of losing agency over their work. Echoing this was American photographer Gregory Halpern when he said that manipulative working methods strip not only the maker of their agency, but the viewer, too—a viewer who is expected to “accept the photographer’s truth in its entirety.”

After publishing Harvard Works Because We Do in 2003—a series of portraits of Harvard’s low-wage contract workers (caterers, security guards, and cleaners) struggling to make ends meet despite the college’s expanding endowment—Halpern hit a creative dead end. The project had a real-world effect on improving the workers’ financial situation, but Halpern ultimately demurred, considering his photographs subpar, concluding that they relied too heavily on what he called “the correctness of my politics” and suggesting that the documentary form was “misused as a form of objectivity.” He argued at the time, with good reason, that the most powerful and effective documentary work encourages viewers to interpret and engage with subject matter independently.

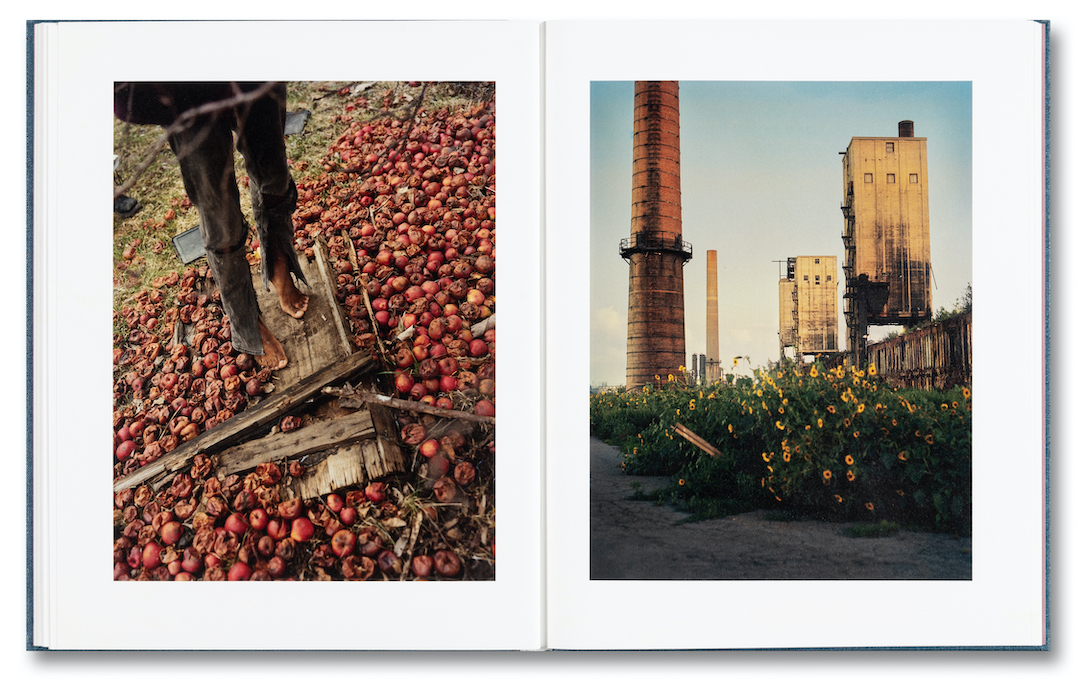

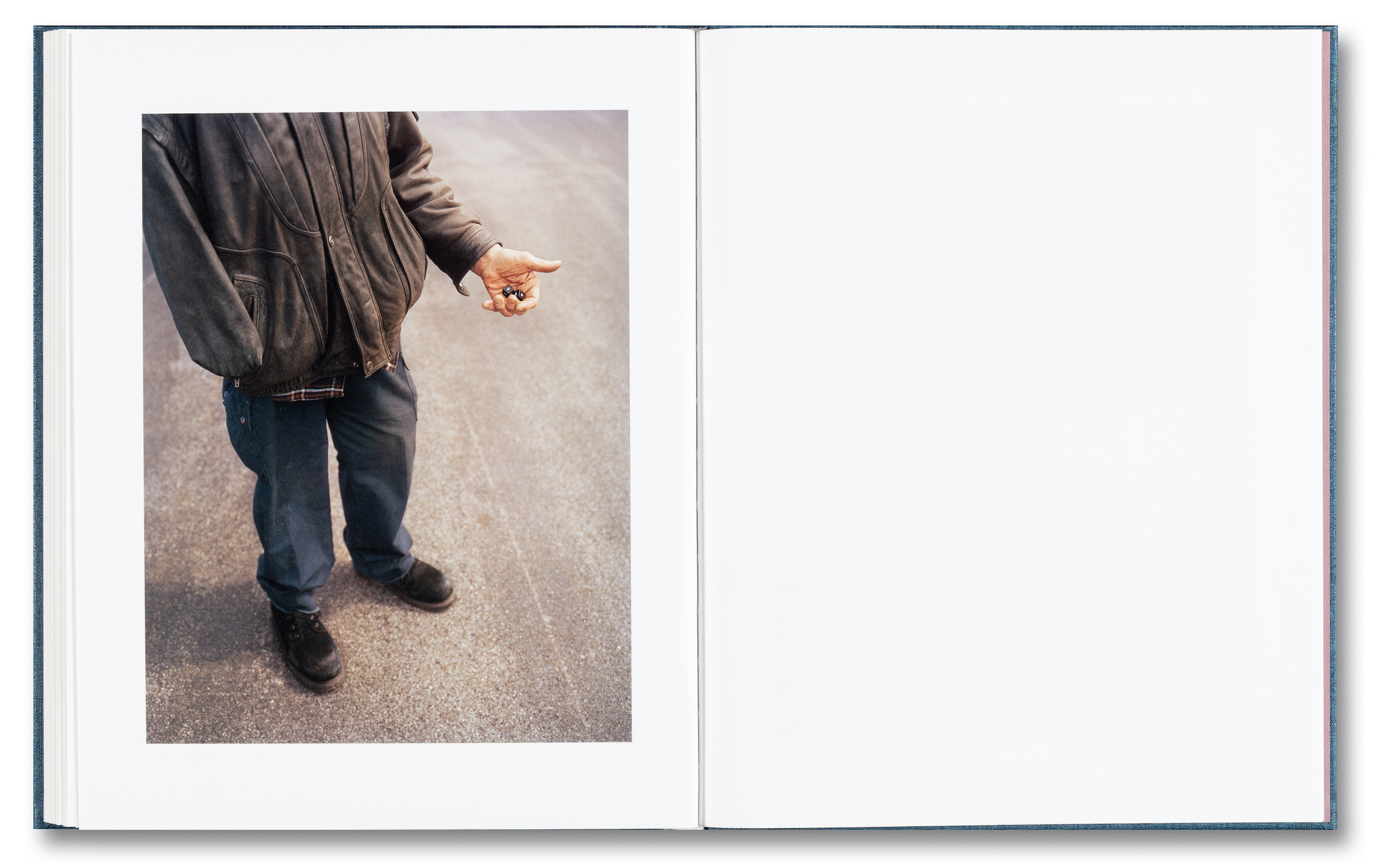

Adrift and unsure how to proceed, Halpern became wracked with doubt: “I had nothing to say . . . I had no idea what to do.” And so he returned to his roots in Buffalo, New York, and every day over the course of six weeks he began to photograph the city’s residents, its streets, and its factories, as well as the detritus and ephemera discarded or ignored when things fall apart, when the social fabric begins to tear. What emerged two decades later was King, Queen, Knave—a work of quiet, tender majesty that contains all the latent and manifest contradictions that constitute the human condition. The monograph is local in its geographic scope but universal in its spiritual and holistic intonations, with Halpern patiently and deftly photographing a number of individual lives in all their pain and grace and hope and despair, of dreams deferred and disappointments momentarily abated. And it is intimate portraits like these that Halpern considers elemental to his work, admitting in a 2018 interview with Magnum Photos that “there is something mysterious and hopeful when one stranger looks into the face of another stranger (via portraiture) and feels something.”

Halpern well understood this complicated and fractured landscape, and was no stranger to exploring the plight of post-industrial America as a visual artist, having previously worked on a separate project for The New York Times, though in a more typically documentary mode. His approach for King, Queen, Knave was altogether more lateral and more digressive, combining “realistic technique with improbably dreamlike visions” in the style of magical realism. In other words, Halpern exhibits a tendency to fuse realism and stylization, or certainly a distilled or heightened form of realism. A case in point: a white deer named April reappears throughout the book: an omen, a blessing, a symbol—for what? There are other repeated motifs—snow and ice, fire and ash (the former representing the unforgiving winter terrain; the latter, heavy industry), as well as signs and symbols of religion (forgiveness, desperation, salvation?). Moreover, the photographs are seasonal in nature: a woman picks flowers in the late afternoon sun, while in the background—muted, softened, almost stately— sits a power plant. Shot on a medium-format Pentax 67, with vintage lenses, Halpern’s work emits a painterly quality—all detail, all nuance, all in the service of, as he puts it, “something transcendental.”

Of the myriad ways that artists over the past two centuries have attempted to define the medium of photography, Paul Graham may have come up with the most lyrically concrete appraisal when he said that it is “nothing less than the measuring and folding of the cloth of time itself.” Here, in this collection of portraits of ordinary Buffalo residents and their environs—a man standing in the deep snow, arms outstretched like an angel; a checkerboard on a porch covered in a blanket of snow; a boy on a bike, all teenage angst and defiance; a vacant house, leaning left, on the verge of total collapse; a woman resting her head on a friend’s arm; a young man on crutches in a sun-dappled graveyard, his right foot, improbably bare and arched, toes barely scraping the warm soil—Halpern has, in his own way, upended (or perhaps even defied) Bertolt Brecht’s assessment that “photography in the hands of the bourgeoisie has become a terrible weapon against the truth.” Thus proving, beyond reasonable doubt, that objectivity and subjectivity can coalesce and coexist as a visual record not only of things as they are but as they seem to be.