Shows

Foraging for Solidarity at the 8th Yokohama Triennale

Mar 15–Jun 9, 2024

8th Yokohama Triennale: Wild Grass: Our Lives

Yokohama Museum of Art and other locations

“I love my wild grass but I detest the ground which decks itself with wild grass.” – Lu Xun

“You can’t swim without drowning; you can’t find an exit unless you hit a wall. It might feel safe to sit in the dark and think quietly, but that path will never lead you to the world of light. You cannot be thoroughly enlightened unless you are thoroughly mistaken.” Kuriyagawa Hakuson wrote these words in his essay Leave the Ivory Tower (1920), calling for artists to actively engage with people and the struggles of the world; and here they were written in large silver lettering around two main galleries at the 8th Yokohama Triennale. These large spaces were also filled with sounds of chanting, yelling, metal barriers rattling, and tear gas being fired, emitted from large monitors to accompany Tomas Rafa’s video documentation of street protests across Europe over the past decade. Looking at artworks, and even watching other videos, while hearing the ambient sound of solidarity and social conflict, was the defining experience of an exhibition that looked back to revolutionary moments and artistic networks of the last century and connected them to the present.

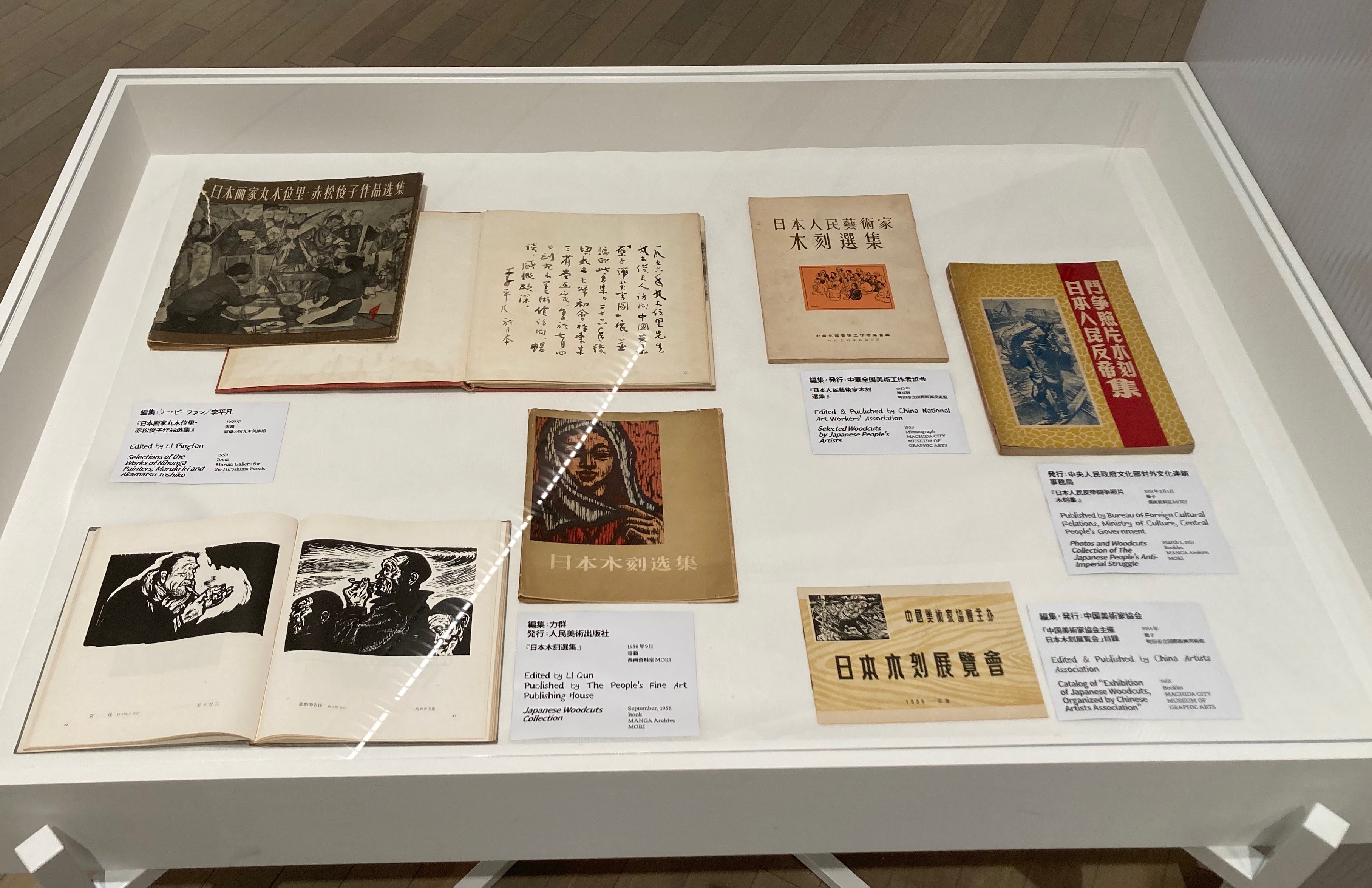

Titled “Wild Grass: Our Lives” by co-curators Liu Ding and Carol Yinghua Lu, the Triennale took the Chinese writer and woodcut artist Lu Xun’s (1881–1936) anthology of essays and poems as their inspiration and historical point of reference. Through Wild Grass (1927), Liu and Lu found a revolutionary thinker whose life’s work was social reform, modernization, and anti-imperialism in the decades after the fall of the Qing Dynasty and the 1911 Xinhai Revolution. A well-known figure in his lifetime, Lu Xun had a life-long connection with Japan, beginning when he went there in 1902 to study medicine and encountered modern Japanese and European philosophy and literature. After returning to China in 1909, he began his career as a public intellectual and writer, and later became interested in woodcut printing as a means to spread his revolutionary ideas and stories more widely to an illiterate population. Participants in a six-day workshop he organized in Shanghai in August 1931 studied with the Japanese printmaker Uchiyama Kakichi (1900–1984) and launched a movement that spread across China and Japan. Throughout his life, Lu Xun remained in touch with Japanese publishers and artists, as well with European artists such as Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945), a volume of whose woodcuts he published. In Yokohama, the curators displayed one of Kollwitz’s prints owned by Lu Xun that shows the 1919 funeral of assassinated German antiwar activist Karl Liebknecht in a vitrine alongside a 1937 Japanese translation of Wild Grass.

The historical context, ideas, and spirit of Lu Xun was crucial to the Triennale’s organization, in particular the 1930s leftwing woodcut movement in Japan and China, examples of which anchored several of its seven sections (the curators worked with five researchers whom they called Thinking Partners). For instance, in the “Streams and Rocks” chapter, a mini survey of Li Pingfan (Li Wenkun, 1922–2011) positioned him as a “key person” in the exchange between the two countries, from his first exposure to the medium in 1931, thanks to Lu Xun, at a Japanese-founded bookstore in Shanghai. He maintained a network of fellow printmakers after his emigration to Japan where he taught at the Kobe Chinese school through the war years, until his forced return to China in 1950 where he continued to publish Japanese books despite accusations and his eventual denunciation as a foreign agent. Furthering the historical links between the two countries in the section “Symbols of Depression,” curators juxtaposed Zheng Yefu’s prints depicting the impacts of the 1931 Yangtze River flood with contemporaneous prints from Ono Tadashige’s Death of Three Generations, a “wordless novel” influenced by figures like Kollwitz, about the struggles of a poor family. One of the revelations of “Wild Grass” was to learn about these artistic kinship and collaborations—what the curators call “global friendship in the name of art”—despite brutal occupations, war, and prevailing societal ethnic prejudices in two countries, and to think about how our world of contemporary art might offer the same potentials for politics and connection outside of the nation-state framework.

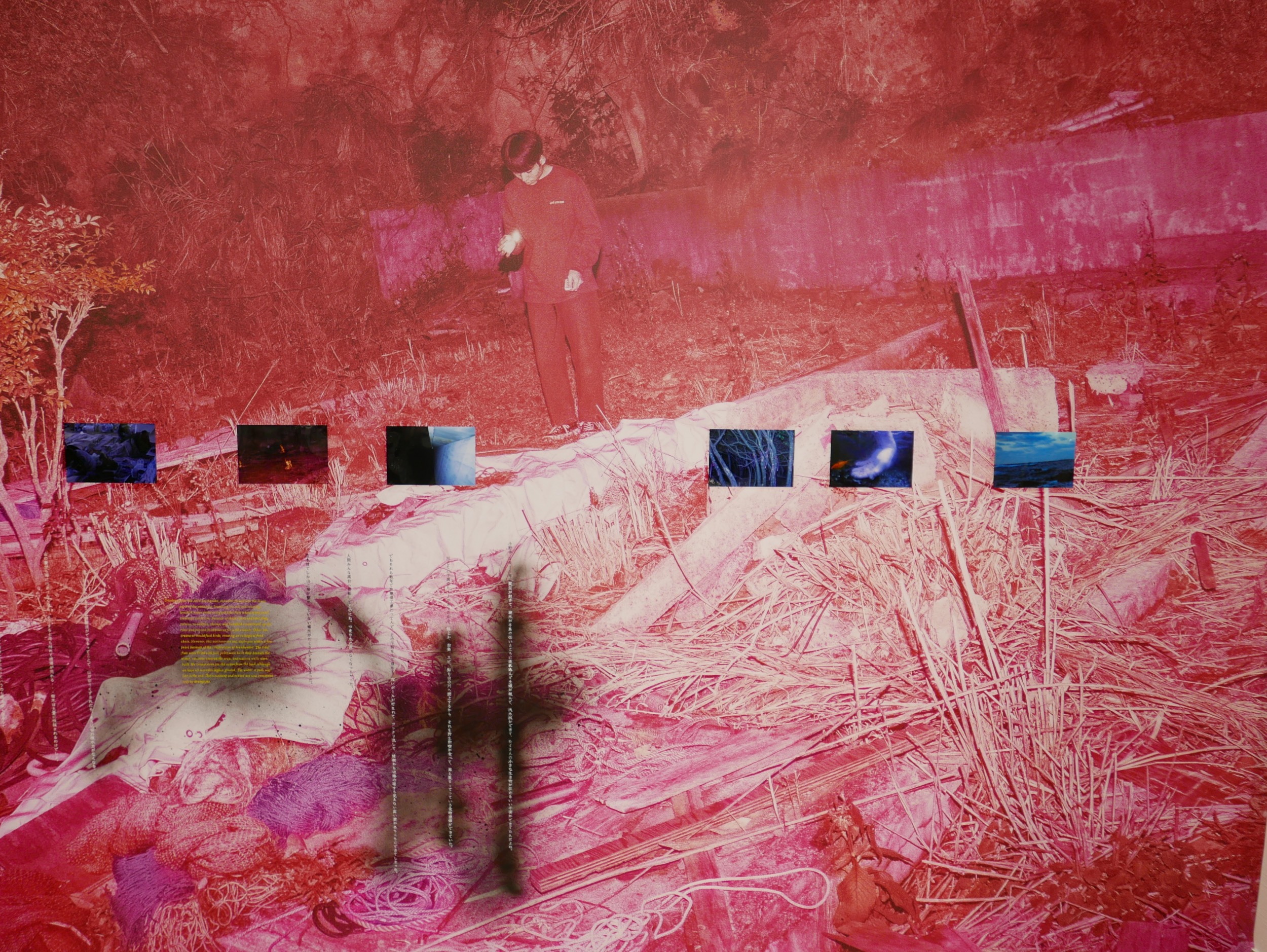

While rooted in history, the Triennale was conceived as a response to the ominous, chaotic present. The skylit atrium of the newly renovated Yokohama Museum of Art (designed by Kenzo Tange and opened in 1989) was filled with another soundscape of strife and conflict. This one came from the video work Repeat After Me (2022) by the collective Open Group who interviewed Ukrainian refugees about the specific sounds they learned to identify from their experience of the Russian invasion; the interviewees mimic the sounds of approaching military vehicles, incoming weapons, or sirens, and then invite the audience to replicate the sounds as if it were karaoke. (This work is also presented in the Poland Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale.) The forum itself resembled a camp, with Joar Nango’s improvised structures made from wood and fabric and compositions of found materials echoing the architecture of the nomadic Sámi people in the Arctic; a tent showing videos of “preppers” talking about food preservation (i.e., pickling) by Soren Aagaard; and the woven fabric forms—one part animal carcass, one part architecture—draped over metal armatures by Sandra Mujinga. Gathering food is a topic explored by Lieko Shiga in a series of red-tinted photographic prints adhered to the museum’s walls, in which the artist records her conversations with a hunter in Miyagi prefecture about our dysfunctional (and often hypocritical) views on nature.

Along with the revolutionary ambitions of 1920s and ’30s, the social protests and movements of the late 1960s and ’70s anchored other sections. “Fires in the Woods,” the two galleries with Muriyagama’s quotes and Rafa’s videos, also feature Yokohama-based Takashi Hamaguchi’s photographs of the student protests against the 1970 renewal of Japan’s security pact with the United States, and Okinawan resistance to the US military bases located there. In this section, visitors also encountered the metal sculptures from the 1950s of Sofu Teshigahara, a prominent avant-garde artist (as well as the founder of the Sogetsu school of ikebana flower arranging); a stack of video monitors showing Black artist Pope.L’s performance, The Great White Way: 22 miles, 9 years, 1 street (2001–09), in which he wore a Superman costume and crawled from the Statue of Liberty all the way through New York City; and Klara Liden’s post-Occupy video Grounding (2018) of her walking and falling dramatically outside iconic locations around Wall Street. While Jeremy Deller used historical re-enactors and former miners to recreate the face-off between the police and striking workers in his monumental video work The Battle of Orgreave (2001), Huang Po-Chih’s ongoing projects involve close collaborations with former garment workers in Taiwan (including his mother posing as an elephant, a symbol of “hard work” in Taiwan, in a series of photographs) and with dispossessed fabric sellers in a recent project in Hong Kong. The Taiwanese collective Your Bros. Filmmaking Group presented an installation of dormitory beds and political action materials made in collaboration with self-organized Vietnamese workers who went on strike in Taiwan over their labor conditions.

Along with a strong emphasis on collective actions, the Triennale’s strong anarchist bent was reflected through the staging of many artworks. The late Japanese musician Ryuichi Sakamoto appeared in a video that showed him dragging a violin through the streets until it broke apart, a performance made in memory of artist Nam June Paik after the Korean artist’s death in 2006. Viewings of this work were interrupted by the sudden ringing of metal alarm bells, an artwork by Atsuko Tanaka that she showed in the first Gutai Art Association exhibition in 1955. Work (Bell) (1955) is still disruptive to this day, and visitors are made uncomfortable by unleashing the loud alarm on others despite the clear instructions to press and hold a button on a pedestal for at least 23 seconds.

Curators and their Thinking Partners dug into the histories of several Japanese artists with strong, independent approaches to the cultural authorities and institutions of Japan. Akio Kobayashi was a self-taught painter from Yokohama who later studied in the US from 1956–60. Upon returning to teach, he began to chafe at how art schools in Japan were not supportive of creative practices, so he started his own independent academy in Yokohama, called the B-Semi School, that had an experimental curriculum focusing on conceptual development and hosted workshops with leading avant-garde artists of the time from Lee Ufan to Sekine Nobuo. Another independent figure was the printmaker and painter Taeko Tomiyama (1921–2021) whose works in the early 1960s looked at the living conditions of miners in Kyushu, many of whom emigrated to South America after losing a labor dispute. Tomiyama later found inspiration from Korean poets such as Kim Chi-Ha, imprisoned by the military dictatorship, and she produced works in solidarity with the Gwangju Uprising of 1980, as part of a lifelong project to connect Japan with its former colonies in Asia. Another fascinating history unearthed in the Triennale was found in “Jomon and the Dream of a New Japan,” which looked at Taro Okamoto’s and Zenzaburo Kojima’s interest in the ancient Jomon civilization (12,000 to 300 BCE) that predates Imperial Japan’s history, as part of their efforts to forge a new cultural identity in the postwar era of the 1950s. Examples of Jomon pottery were displayed next to Okamoto’s black-and-white photographs and Kojima’s paintings.

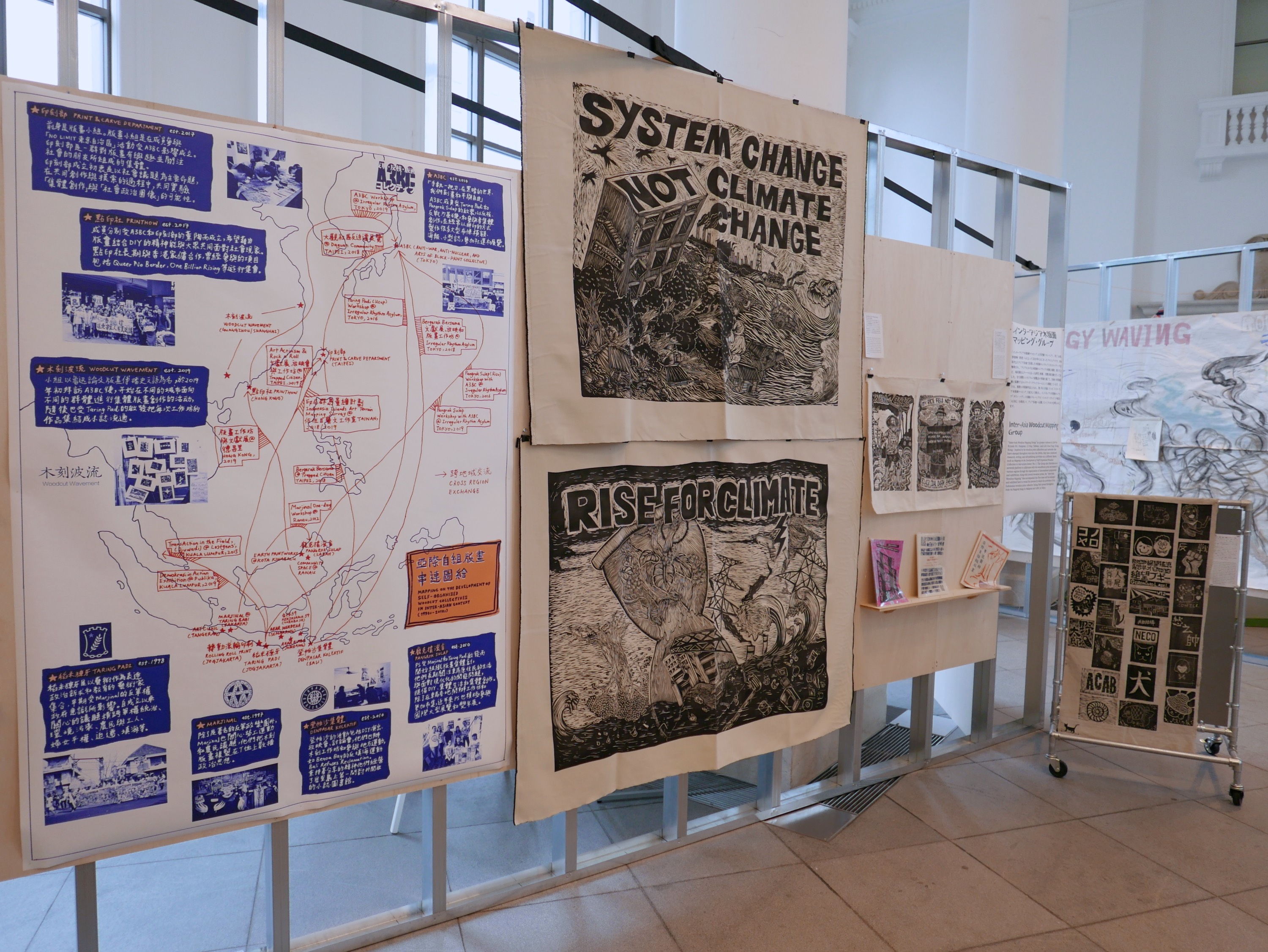

For all its historical scope and period-specific research, “Wild Grass” also oriented itself toward the contemporary ethos of zine and printmaking collectives. This was most evident at the offsite venue of the former Daiichi Bank in Yokohama where curators imagined “the kind of society we want to see, ‘here and now’” in “All the Rivers” (the title comes from Israeli writer Dorit Rabinyan’s novel about a romance between a Jewish woman and a Palestinian man). This neoclassical building housed projects by several printing and publishing organizations, including the Inter-Asia Woodcut Mapping Group, whose regional focus on groups in East and Southeast Asia (such as Taring Padi and Pangrok Sulap) and on the printmaking medium was immediately reminiscent of 1930s-era practitioners. From Japan, curators presented Yamashita Hikaru’s projects that put found or second-hand materials (clothes, consumer goods, old paintings), back into circulation via his artist projects and quasi-storefronts or imitation vending machines, while the Taiwanese duo of Liao Xuan-Zhen and Huang I-Chieh presented The Parthenon project that revisits the activist legacy of Taiwan’s 2014 Sunflower Movement and now serves as an ongoing platform for social movements. At the former bank and elsewhere in the exhibition, the curators presented poems about contemporary Manila by Carlomar Arcangel Daoana, printed on large rolls of paper and mounted on wooden boards, as sculptural-textural insertions into the exhibition.

Ultimately, the Triennale proposed not only a historical vision but an awareness that the tensions and turmoil of the last century continue into the present, and still await resolution. As curators, Lu and Liu look to collective and individual actions that speak to the agency of the individual, rather than that of the state. (It almost goes without saying that the Triennale could not have been staged in mainland China, where the curators are based, despite the high regard in which Lu Xun, Mao Zedong’s favorite writer, is still held by the People’s Republic.) At the national and international level, while politics is conflict-ridden and increasingly violent, the curators propose that there are person-to-person and artist-to-artist networks that still facilitate conversations across divisions and pursue the planting of seeds for generations to come.

HG Masters is deputy editor and deputy publisher at ArtAsiaPacific.