Shows

Entangled Tikar: Yee I-Lann and the Politics of Mat-ness

“Borneo Heart in Kuala Lumpur”

Multiple locations, Kuala Lumpur

Feb 25–June 18

How would a Borneo-centered exhibition infiltrate the concrete jungle of Kuala Lumpur and reverse the direction of cultural distributions, momentarily disrupting the complex power balance between the two “lungs” of Malaysia? How did said exhibition tackle issues such as inclusive engagement, flexible display, and space-making for artistic creation, all while celebrating the tradition, culture, and knowledge of Sabahan Indigenous peoples without exotifying or othering them?

As one followed the trail of “Borneo Heart in Kuala Lumpur,” the heart-child of Yee I-Lann and a diverse array of creative collaborators, the aforementioned questions continued to echo and beckon us into mutual dialogues. Spread across five locations throughout the capital, “Borneo Heart” began with “Tikar/Meja” at The Back Room, a “mat-ness” manifestation of the symbolic tension between tikar (the mat) and meja (the table). To this day, the Indigenous peoples of Borneo still value the tikar, which has many names and is weaved from a myriad of materials, as an object used for communal gathering and local hospitality. Working with a predominantly female group of Bajau Laut weavers, Yee sheathed Back Room’s white walls with multichromatic tikars, which are entangled with meja motifs—an imported visual language of Portuguese origins, representing colonial intervention and administrative dominance.

Not merely contained within a white cube, Yee’s tikar spread into the compound of Zhongshan Building, where Back Room nestles, and transformed into a suspended mat-installation above a coffee shop, where passersby could gaze up at its textile presence to decipher its interlaced text. A metaphor for something easily neglected, the monolithic tikar here looms as a phantom of lost etiquette—a silent reminder of pre-colonial forms of human relations. Featuring the tikar in the first stop of the exhibition, Yee and the weavers invited us to reflect on our relationship with power-imbued objects and immerse ourselves into the tikar’s welcoming terrain.

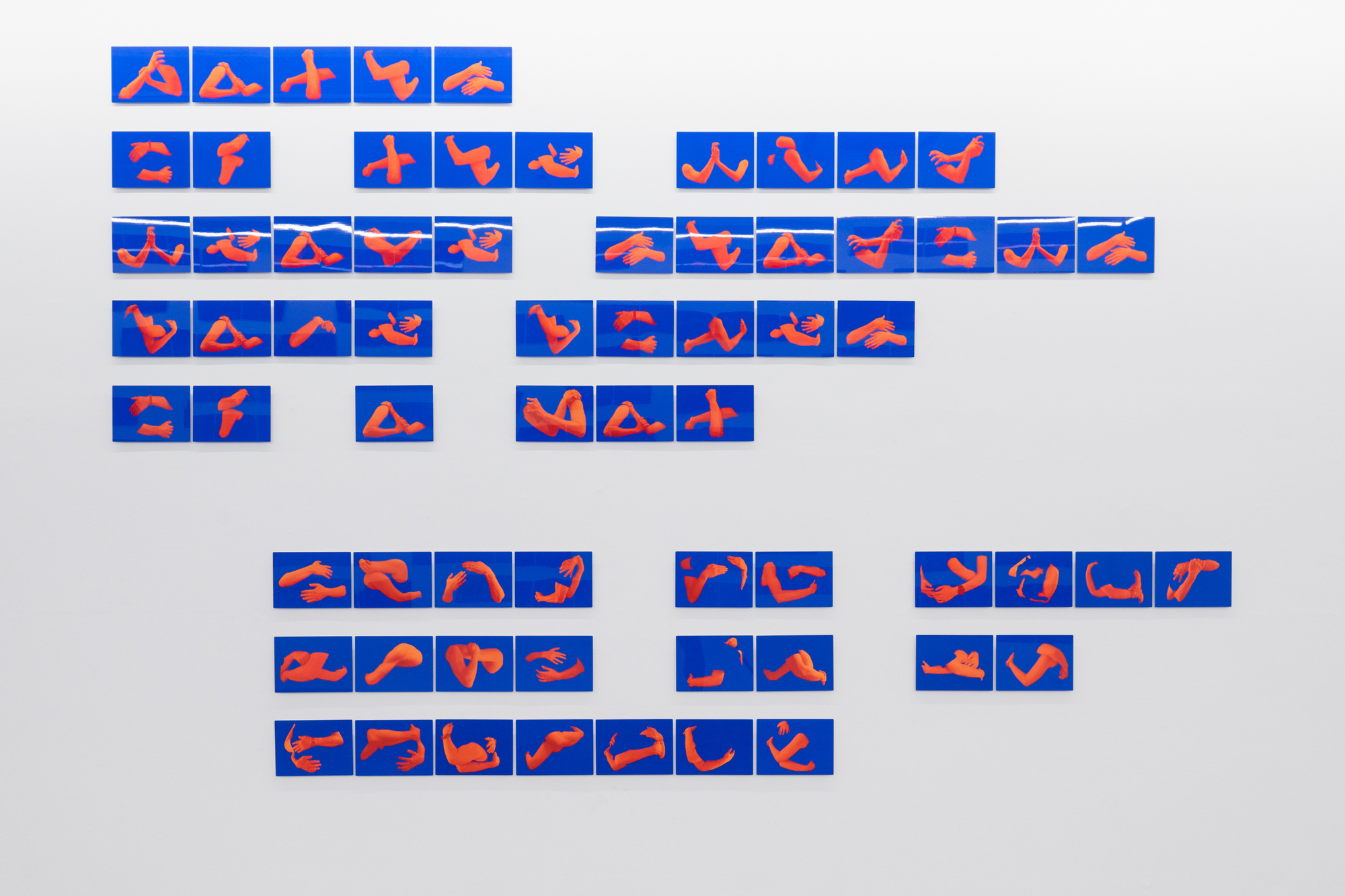

Aside from her deep engagement with collaborative projects, Yee is also known for her photomedia practice, where she attempts to access and depict the human condition on digital prints. At A+ Works of Art, a contemporary gallery braided into the Trade Center in Jalan Sentul, Yee again unleashes three photomedia essays that consumed the space. One of them was titled Rasa Sayang (2014–21) which consisted of dye-sublimation prints on navy-tinted aluminium that depict pairs of bodiless arms in various positions of affection and conflict. As the viewers tilt their head trying to decode these cryptic ciphers, the prints are revealed as love poems soaked with longing for intimacy.

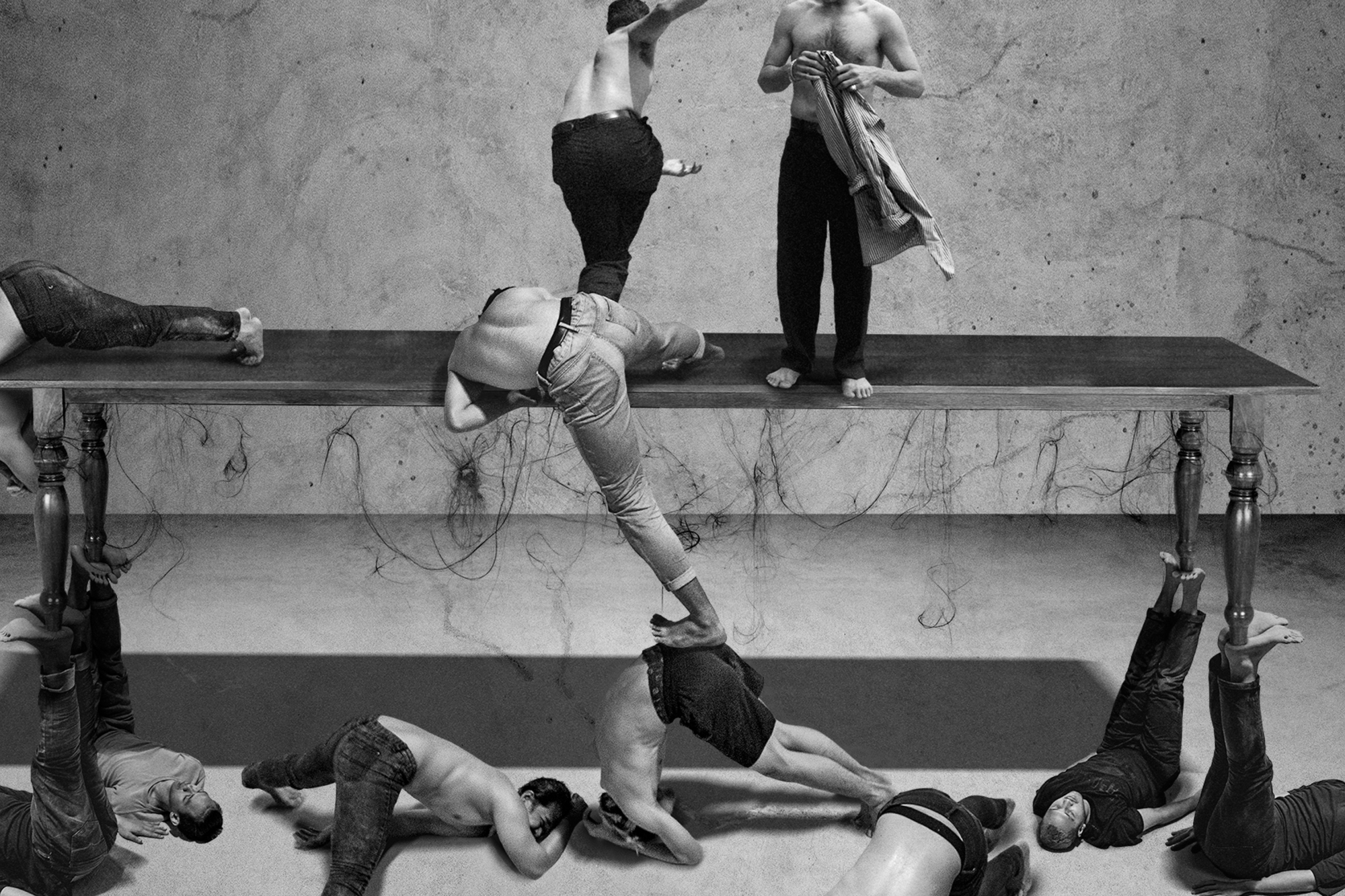

Rasa Sayang cracked open the portal that led us to the overarching title “Allom! Amatai! Allom!” inspired by when Yee asked the weavers how they measured their tikar and the chief weaver replied “Life! Death! Life!” as she measured the mat with her footstep. This visceral measurement resonated with Yee’s pondering on how to measure affection, perhaps through the length of an embrace. This musing on measurement-as-worlding echoed in the other photomedia essays. In Measuring Project: Chapters 1–7 (2021–22), different bodies are placed in contrasting degrees of relatedness in relation to either the egalitarian tikar or the regnant meja, a stark contrast between circular connectivity and disrupted proximity. Different methods of measurement belie different value systems, and Yee is swimming against tidal waves of colonial mentality to return to indigenous forms of relating, thinking, and collaborating. This self-decolonization is also expressed in Untitled Self-Portrait (2017), where she weaves a mnemonic montage that traces her homecoming to Borneo in 2018, a landmark in her return to more organic ways of being with(in) the world.

Yee’s journey to meet the tikar took multiple routes, and at Ilham Gallery viewers were graced with two of her video works shown side by side. While Tikar Reben (2020) is a drone-shot video that shows the Bajau Laut weavers crossing the ocean while carrying a rainbow, serpentine mat—a symbolic and ritualistic act for horizontal meeting, rebirth, and communal politics—the adjacent Pangkis (2021) presents a group of seven Bornean dancers sharing a seven-headed lalandau hat while performing in semi-synchronization and uttering calls for war—an expression of masculinity tied to indigenous rite of passage yet now struggles to find its footing in modern societies. Other large-scale tikars were also on display, detailing the diversity in lexicon, materiality, and functionality of tikar across different Bornean localities. Finally, one ended the whirlwind celebration at Rumah Lukis, an art space on the outskirts of Kuala Lumpur and the host for Balai Bikin (2021– ). A mat-covered platform, Balai Bikin invites people to sit down, rest, chat, and read about the process of conceptualizing “Borneo Heart,” highlighting the pivotal roles and labor of different indigenous creators who collaborated with Yee to birth the works. “Borneo Heart” ended on an optimistic note: looking forward to the future of alternative implementations of the celebration and of weaving across different visual languages, geographies, economics, and stories—all centered around the humble yet profound symbol of the tikar.