Shows

“Elsewhere and nowhere else” and “The house is full”

With artistic production by non-white New Zealanders too frequently framed by a politics of representation, it was a relief to see the two group exhibitions “Elsewhere and nowhere else” and “The house is full,” curated by Vera Mey and Dilohana Lekamge, respectively. Viewers were asked to side-step prevalent frameworks of national identity in Aotearoa New Zealand, and to set aside the sometimes hand-wringing concerns of identitarianism. Instead, the exhibitions helped to shift our conversations from an uncritical multiculturalism to a form of multi-contextualism.

“Elsewhere and nowhere else” took as its starting point the work of three New Zealand artists who live “elsewhere.” We were invited into the exhibition by Kah Bee Chow’s Portals (2022), a series of vinyl decals that borrow from the vernaculars of Straits architecture in Malaysia, accompanied by chandelier-like sculptures of materials from everyday objects—lurex and latex, wire and wrought steel, plastic and paper clips. Exquisite details carried through from one artist’s work to the next: The spiky cable ties looped to form makeshift handcuffs in Yuk King Tan’s Eternity Screen (2019) echoed the New York bird-perching prevention spikes in Li-Ming Hu’s installation Where is the art? (2022), and even the spiky pineapple on a mock altar in Chow’s Portals.

The artworks demonstrate a studied ambivalence for national identity. They require us to think beyond ideas that separate the local from the international, and to instead prioritize the mutuality of concerns across national borders. Consider Tan’s Eternity Screen as an example, which is anchored in a commitment to pro-democracy movements. The artwork makes reference to handcuffs as objects of arrest and control. Even as the installation responds to the 2019 protests in Hong Kong where Tan lives, the concern about the backsliding of democracy is not unique to her context; it is shared across the globe, from regions as diverse as the United States and India.

In Chow’s Portals, what is compelling about her reference to Straits architecture is the style’s syncretism. The hybrid form incorporates Chinese and Portuguese influences, as well as British and Malaysian, among others. In her artistic practice, Chow often works with forms of protective architecture, including mechanisms of enclosures and gates. So, what does it mean for a syncretic architecture to offer protection? In a time when national identities risk consolidation through essentialist and exclusionist means—that is, by doing away with whatever and whoever is otherized and rendered external, as seen in the ill-treatment of Muslim Indians in India, or the fear of the outsider that buoyed the Brexit vote—I read the syncretism in Portals as a poetic and powerful corrective.

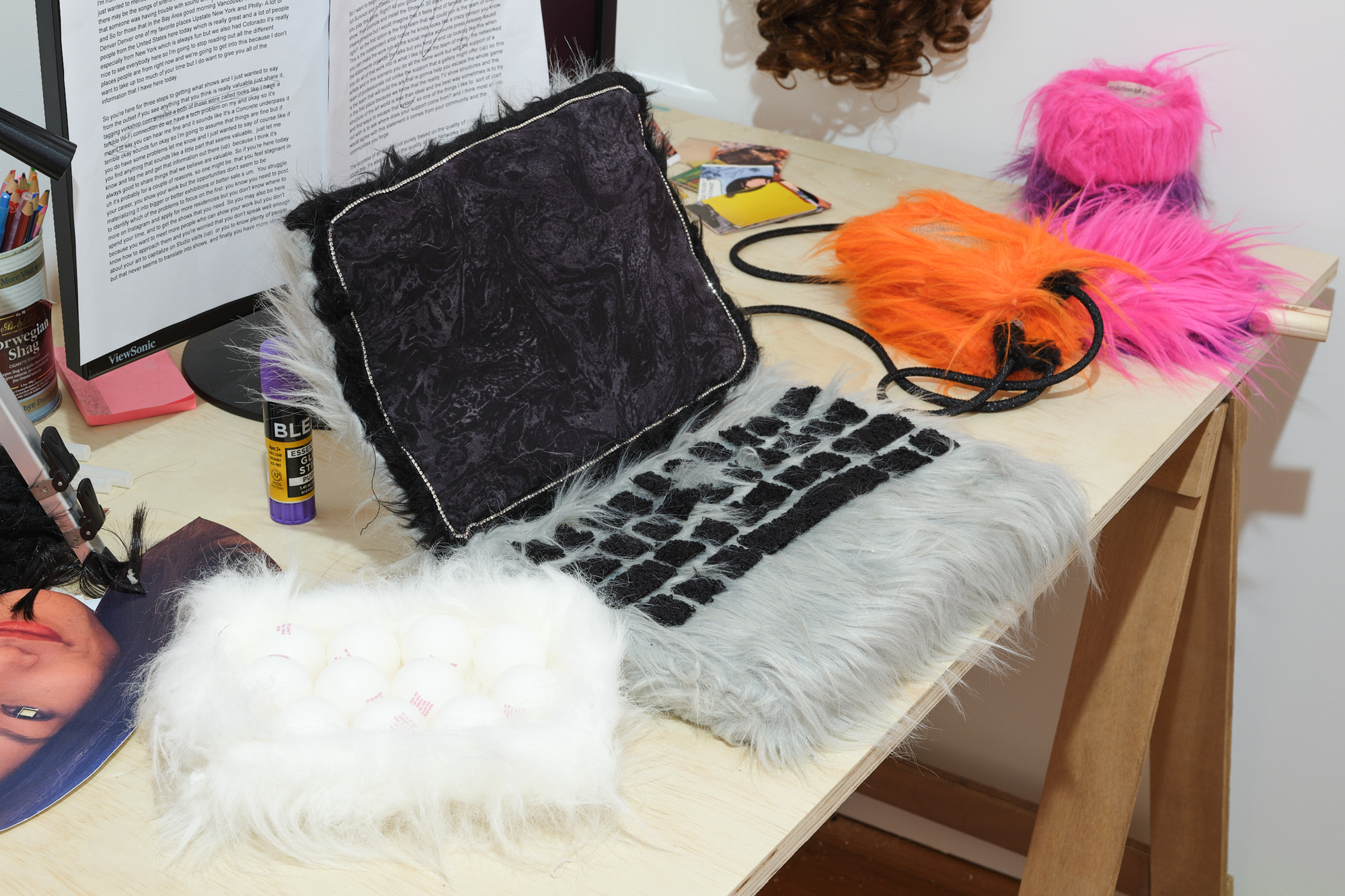

Of concern in Hu’s Where is the art? is the means to sustain life as an artist while socioeconomic precarity seeps across national borders. The recreation of an artist’s studio contains a busy assortment of materials: faux fur and foam, a cotton curtain printed with the artist’s visa applications and letters of support, and ping-pong balls with neoliberal dictums for mobility and marketability, such as: “Success as an artist is not based purely on the quality of your art,” “It is also based on the quality of your network.” Some of these objects reappear as props in the video shown on a TV monitor on the studio’s exterior, where Hu re-enacts the role of a puffed-up market strategist giving a workshop, as if artists might resolve material impasse with a better communication plan.

The curatorial note by Mey elaborates on the possibility of common concerns across the binaries of local and international, inside and outside: “Our entanglement with an ‘out there’ is much more complicated.” This is perhaps why Mey recalls the Mahabharata verse that gave the exhibition its name: “What is here is elsewhere. What is not here is nowhere else.”

If “Elsewhere and nowhere else” stepped us outside the topic of national identity, then “The house is full” stepped us right back in, asking: who is marginalized by prevalent frameworks of national identity and art history in Aotearoa New Zealand? Specifically, when artists in the 1970s questioned the notion of a singular national identity, who of those have not been recognized for their contributions?

We were invited into this question by Emily Karaka’s painting, where a medley of people emerges from richly hued shapes textured with brusque strokes and dashes. Aptly named In the Mixing Bowl (1977), this was Karaka’s first publicly exhibited work when it was shown 43 years ago in Ponsonby. However, Lekamge noted in the curator’s introduction the double standards placed on the Māori artist’s work when compared with her white colleagues working in the field of abstract expressionism: “[Karaka’s] artistic oeuvre has been considered politically driven protest art, whereas her significance as a figure that contributed greatly to the abstract expressionist movement in Aotearoa is downplayed in comparison. This is largely due to the fact that Māori art has been understood in a racialised and politicised way, in comparison to the apolitical lens that Pākehā men have historically been afforded.”

The interplay of national identity with narrative constructions of art history was furthered by the inclusion of Teuane Tibbo’s four paintings depicting Samoan village life, such as scenes of a wedding, and curious quadrupedal creatures. In these works, the forms of swimmers, paddlers on canoes, and even the ocean are simplified to single strokes and casual dabs in tertiary colors. Like Karaka, Tibbo’s work shows visual sympathies with the art movements of its time, and there was an asymmetry in its reception. In contrast to her white peers whose work was framed as primitivist, Tibbo’s work was categorized as primitive—or as Lekamge quoted in her curator’s note, as “‘genuine dyed-in-the-wool primitive,’ in a belittling manner.”

Shown alongside Tibbo’s paintings were 16 photographs from the 1970–80s by Parbhu Makan, who captured farming life and cricket-playing children during his travels to India, as well as the family functions of Indian New Zealanders, as in Chandu’s Wedding (1973–75) in Wellington, Amrat’s Wedding (1981) in Ponsonby, and Ramesh’s Wedding (1981) in Grey Lynn. The titles also made reference to an uncle Dullabh, aunty Hari, and father, suggesting that in these photographs were some of Makan’s relations. Recent scholarship, such as Jacqueline Leckie’s book Invisible: New Zealand’s history of excluding Kiwi-Indian (2021), has detailed the ways that Indian New Zealanders have been perpetually left out of mainstream narratives of the history of Aotearoa New Zealand. And so, it was gratifying to see Makan’s work from almost 50 years ago, not for a politics of representation but for recognition. Through this exhibition, Lekamge provided a context in which to recognize Makan’s contribution to narratives of national identity against the backdrop of Indian New Zealanders’ invisibility.

On the opposite wall to Makan’s works were John Miller’s photographs from that same decade. With crowds of deliberators at rural court houses and landscapes north of Matawaia Marae, Miller’s images show the 1970s Ngāti Hine land disputes. During this time, Miller photographed other important moments of activism, including the anti-Vietnam War movement and the Springbok Tour protests, but this series and the legal dispute it records is less well known. Significantly, Miller was also an active participant in the land dispute. Not only was the house full in the exhibition curated by Lekamge, but so were the protest sites, the playgrounds, the fields, and the fale.

The two exhibitions sat together in space as if a couplet on a page, and together probed at the notion of national identity. Whereas “The house is full” interrogated from the margins of the question, “Elsewhere and nowhere else” looked outside the frame. Anchored in the artistic practices of non-white New Zealanders, both exhibitions helped to reveal the limitations of national identity as a framework for making sense of contemporary art.

“Elsewhere and nowhere else” and “The house is full” were on view at Te Tuhi, Auckland, from June 12 to September 4, 2022.