Shows

Control and Chaos in “Burn | Overflow”

Takuma Nakahira

Burn | Overflow

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

Feb 6–Apr 7

The late 1960s—marked by the May Revolution in France, civil rights tensions in the United States, and the Vietnam War’s escalation—saw societal norms questioned as mass media became omnipresent. In addition to world events, Japan saw protests erupt in resistance to the continued operation of US military bases within its borders. In this context, Takuma Nakahira’s photography stood out as it probed the medium’s essence and sought a new communicative approach that escaped the dangers of media's commodification.

Curated by Rei Masuda, “Takuma Nakahira: Burn | Overflow” at The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo provided an expanded view of Nakahira’s influence on photography’s discourse (as a crucial figure in its intellectual landscape at a time when images were gaining new significance) and highlighted the relevance of Nakahira’s work as a response to today’s media oversaturation.

Nakahira (1938–2015) was an editor of the leftist magazine Gendai no Me (Contemporary Eye) in the mid-1960s, a role that exposed him to global discourse on visual culture and led him not only to make his own photography (at the prompting of the legendary photographer Shomei Tomatsu), but also to write about it. His editorial work blossomed and evolved in 1968, when, alongside Koji Taki, Yutaka Takanashi, Takahiko Okada, and, later, Daido Moriyama, he started the independent magazine Provoke, under the banner “Provocative Materials for Thought.” As Nakahira accelerated his activity as a photographer, his writing also developed as he became a regular magazine contributor. His highly influential photobook For a Language to Come (1970), for example, was comprised of his photographs and accompanying texts. At that time, Nakahira’s photography was labelled as are-bure-boke (grainy, blurry, and out-of-focus), an iconic look that was appropriated by others and stayed in photography discourse for decades to come.

For a photographer whose work is best understood as part of an interdisciplinary practice, this retrospective successfully synthesized a robust exploration of Nakahira’s work. Magazines shown in cases or mounted on walls were prominently displayed, highlighting the importance of Nakahira’s magazine work as an editor, writer, and photographer. The exhibition also made it clear that Nakahira did not stop being an editor after he started shooting images. Rather, he expanded the enterprise of an editor to include the functions of authorship, which was part of being an active agent in the dissemination of ideas. Japan’s vibrant media landscape made this possible. The printed page, given its ability to combine image and text in a format that could reach a wide audience quickly, was the ideal medium for Nakahira.

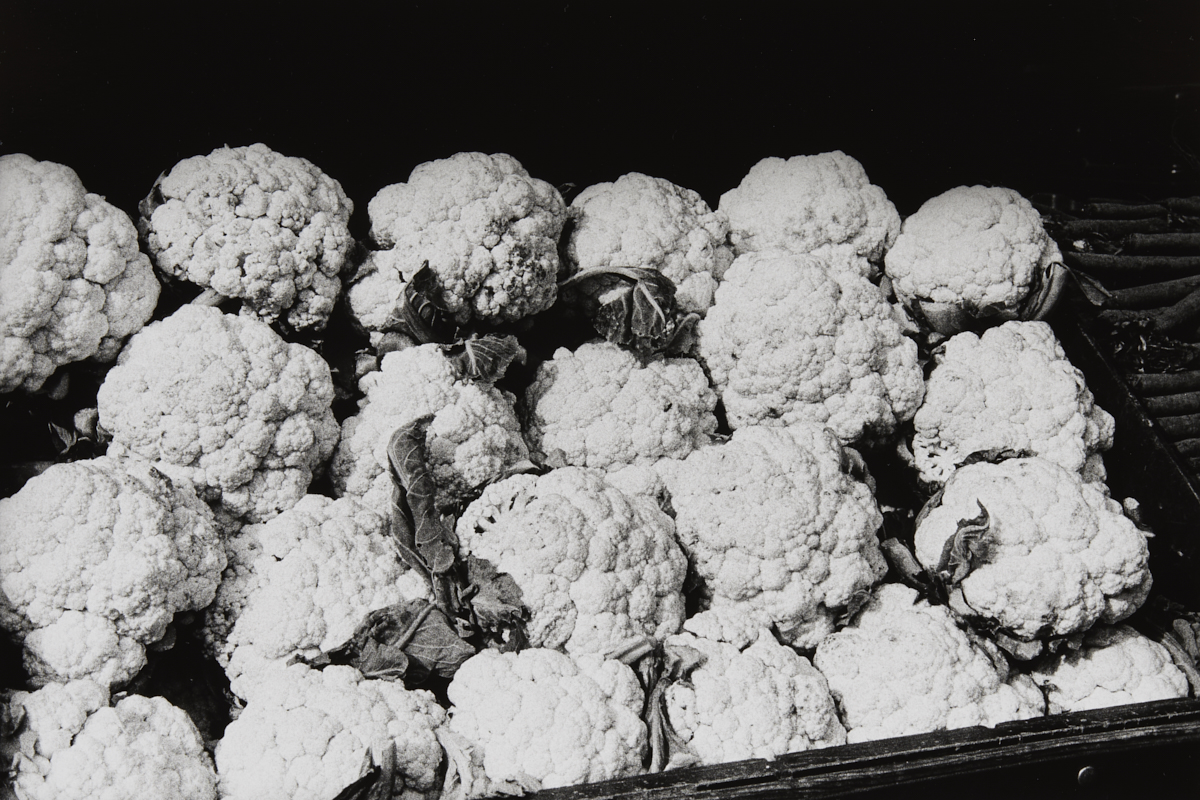

This is vividly demonstrated in his series La Nuit from 1969. That same year Nakahira was invited to participate in the sixth Paris Biennale, but instead of displaying darkroom prints enlarged from negatives he chose to show photogravures, a printing technique synonymous with the mass reproduction and distribution of images. Gravure was an extremely common reproduction technique for photography magazines and, when used as monochrome on matte paper, was a signature look for postwar Japanese photography: a rich, charcoal-like matte black that seems to absorb light. Nakahira’s choice of monochromatic gravure distinguished it from the shiny and vibrant techniques typical for color advertising pages in magazines.

Two years later, for the next Paris Biennale, Nakahira upped the ante to create a legendary installation of photographs, which was partially recreated for the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. In Circulation: Date, Place, Events (1971), he furthered this exploration, presenting a dynamic installation that was continuously updated with new images. Rather than framed, the prints were mounted on the wall as part of an amorphous tableau. The installation was continually updated while he was in Paris photographing, and then replacing, images. This embodied Nakahira’s aim to make the process of capturing and sharing images as immediate as possible. Nakahira’s shots feature some recurring gestures: people caught looking directly at the camera, showing reactions that could be interpreted as hysterical. There are sequences of images that show a progression of incremental and incidental change, such as a car pulling out of a parking stop as seen from above. Women appear as either printed reproductions or mannequins. Moreover, there is an unclear frame-by-frame progression that moves both horizontally and, at times, vertically in stack.

A key pivot point in Nakahira’s body of work can be seen in Overflow (1974). Shown in 1974 as part of the group exhibition “Fifteen Photographers Today” which was organized by The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, Overflow is comprised of 48 unframed vertical and horizontal chromogenic prints clustered together in an amorphous cloud formation. The images were shot between 1969 and 1974, the year Nakahira published a collection of essays titled Why an Illustrated Botanical Dictionary? In this book, he articulated a concept of photography that rejected the are-bure-boke approach espoused during the time when he worked on Provoke. Instead, in his search for a methodology that would answer the large question of what is photography, he described a different approach: images were to be shot outdoors in bright daylight, in color, and in a vertical format.

In 1977, Nakahira fell into a coma due to extreme alcohol consumption, resulting in permanent memory loss, an event that precipitated a major transformation of his work. This retrospective, which was divided into five chronological sections, dedicated the first four to his work leading up to 1977; the final section covered nearly four decades of his output after his recovery. Nakahira’s later work is characterized by vertical, color images captured in bright daylight, consistent with his ideas included in Why an Illustrated Botanical Dictionary? In contrast to his work up to this point, he presented his prints in pristine grids of large color prints.

The grit, chaos, and immediacy of his earlier work were gone. It is arguable whether his post-1977 work was conceptually driven or not, though the horizontal and vertical dynamics present in his earlier work are evident in kirikae (2005– ) (which translates to “switch” or “conversion” and can be interpreted in many ways). A motif in one print (sunlight casting a pattern on the arms of a figure asleep in the park, for example) switches to something else (the elongated seed parts of a conifer tree) in an adjacent image. There are similarities and discordances between the images that become visible as the eye (and body) move through the installation, producing a visual dynamic reminiscent of Piet Mondrian’s painting Broadway Boogie-Woogie (1942–43). But where Nakahira’s black-and-white works of the 1970s referenced mass media and the reader-as-consumer perspective, his installation of the 2010s placed the individual within the images, thereby serving as specific and local context for the photography. As such, the values of specificity in space and time connect with his 1970s work. Similarly, he used installation to challenge conventional notions surrounding the photographic print as commodity.