Shows

Comparing Silk, Bamboo, and Video at the Sigg Prize Exhibition

Back in early March, I visited the Sigg Prize exhibition at the M+ Pavilion in Hong Kong, wondering whom I would select if I were a member of the jury. I decided that there was just one artist, out of the six, whose work rises to the level of international importance that the prize seeks to highlight. I subsequently wrote an article explaining my choice, but it went unpublished because the M+ Pavilion closed down again during the second wave of Covid-19 infections in Hong Kong. And then while watching the rest of the world be transformed by the pandemic, I convinced myself there shouldn’t be a winner at all.

In a previous article, I wrote about the dubious logic and optical pitfalls of the art award, particularly in this time of crisis. I realize the Sigg Prize was set in motion in the BC (before Covid-19) era, having evolved from the Chinese Contemporary Art Award established in 1998 by collector Uli Sigg, who donated part of his holdings to M+ and sits on the organization’s board. But the opacity and at times arbitrariness of how art awards are judged is a problem irrespective of time and place, and one that I believe applies to the Sigg Prize. For one, the finalists are incomparable in terms of the works they presented and their careers to date, even though curator Pi Li attempted to frame their practices through the contested concept of “identity politics,” which has come to have alternately positive and reactionary connotations depending on who is discussing it. Indeed the shortlist is meant to emphasize “different generations and geographies,” as M+ director Suhanya Raffel writes. The six nominated artists were born between 1964 and 1990, effectively spanning three or even four cultural generations, with vastly different life experiences, educations, and conceptions of art—great to represent but impossible to compare. It was also noticeable and perplexing to me that that the three youngest artists in the exhibition all presented works that are now several years old—though their careers are fast evolving—while paradoxically, the three older artists were allowed to create new commissions in their more established, signature styles.

Shen Xin—the youngest finalist, born in 1990—displayed their 53-minute, four-channel video installation, Provocation of the Nightingale (2017), originally shown at the New Museum Triennial in 2018. The first chapter is a long sequence, in which two Korean actors playing a Buddhist nun and a “manager of a genetic testing company” recite a slow, at times tendentious, dialogue about spirituality in a capitalist context. The second, third, and fourth chapters of the installation, which are screened on three other walls, are similarly oblique and overly contrived—two actors breathing heavily; a recording of a television monitor screening charged documentary clips about eclectic topics ranging from Uighur musical traditions to the Japanese military’s forced enslavement of women during World War II; and then finally a vocal dialogue between two people reflecting on their ethnic identities after receiving the results of a genetic test. The work alludes to powerful subjects and is evidence of the artist experimenting with formats of presenting materials, but remains experientially unresolved.

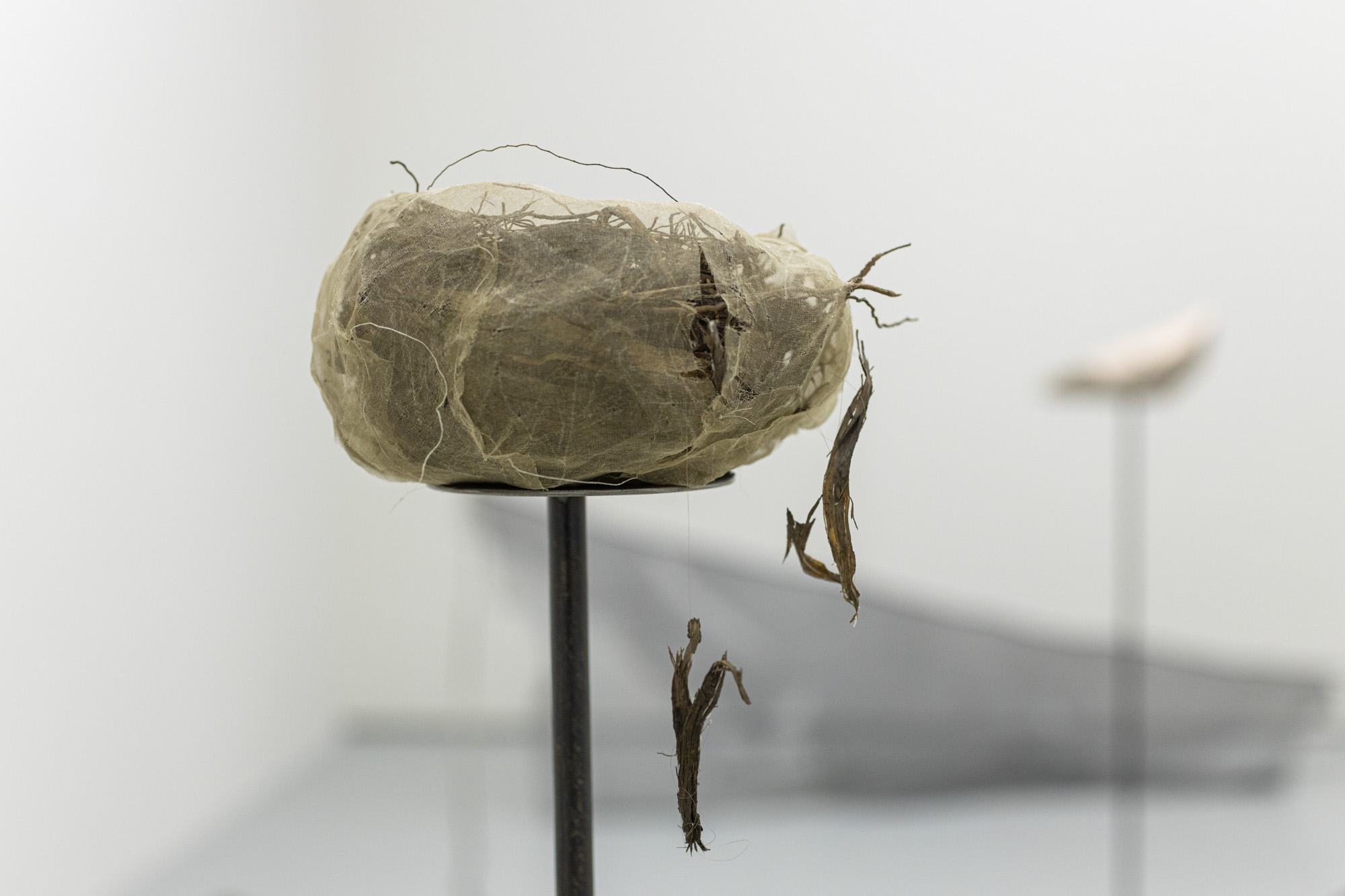

By contrast, Hu Xiaoyuan gets a small room of her own for a newly created installation, Spheres of Doubt (2019), which was commissioned by M+. Born in 1977, Hu Xiaoyuan was featured in Documenta 12 way back in 2007, and in the New Museum Triennial in 2012. The artist has a developed a signature practice involving xiao, a type of raw silk, which she uses to cover objects before painting their textures onto the fabric. In Spheres of Doubt, there are two bent rusted rods, presumably from a construction site, over which the artist has draped the xiao. Various other objects—a lemon, a bar of soap, a ceramic bowl, a glass, a piece of wood—had been similarly covered and their textures transferred to the silk. Some of these items are presented on small metal pedestals formed from metal poles on concrete bases, and in one corner there is a marble column with two clumps of human hair emerging like pigtails. With a strongly developed formal language, the installation is fundamentally formalist—about layering, concealment, exploring the line between found objects and Hu’s interventions—and has a strange kind of self-possessed elegance, even from these construction-lot substances. Made of materials from the world, the work also feels remote from it. It’s no one’s idea of beauty somehow beautifully presented.

The second youngest finalist is Tao Hui, born in 1987, who primarily works in video and has made some good short experimental films in recent years, often in overt homage to famous directors and Chinese television melodramas. Tao Hui’s installation Hello, Finale! (2017), shown at the 2017 Hugo Boss Asia Art award, resembles an airplane’s first-class cabin. On a low dais, there are nine single armchairs facing gray, headstone-like plinths embedded with monitors, and you can sit, one at a time, to watch each of the short videos. Shot in Japan with Japanese actors, the short films feature a single character talking on the phone; we can only hear their side of the conversation. In one, a boy walking home from school seems to think he exists in a video game; another depicts a man standing in a cemetery under a black umbrella, breaking up with the woman with whom he has been having an affair. They are well written and acted, with a light touch of camp. The format is accessible and engaging but they become a little repetitive and I questioned what they add up to collectively.

Lin Yilin’s trio of performance-videos are shown on video monitors embedded in freestanding walls facing the pavilion’s glass wall. Lin’s three-channel video of a performance in Rome, The Back (2019), shows the artist dressed like a Franciscan monk standing in front of the Pantheon reading the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China in Italian. He then winds the three versions of the constitution (in Chinese, English, and Italian) into a rope, which he coils around himself and later members of the public use it in a tug of war. According to the very first sentence of the wall label, the work was “inspired by the controversial amendment to the Chinese constitution in 2018”—and very conspicuously does not continue to say what that amendment is or why it was controversial. In Lin’s other two videos, we see him rolling on the floor of the Solomon R. Guggenheim for 45 minutes (The Second 1/3 Monad, 2018), a protest, in spirit, against the western canonization of art, and walking on stilts through the old arcades of Guangzhou (Typhoon, 2019) to mourn their disappearance by waves of development—performative acts that today feel dated. Born in 1964, Lin Yilin was a member of the seminal Guangzhou artist group Big Tail Elephant, and has made some iconic, art-historical-worthy performances, including Safely Maneuvering Across Linhe Road (1995), in which he moved a wall across a multi-lane road one concrete block at a time as it served as a barrier to oncoming traffic, but these works don’t have the same resonance today.

The third of the Beijing-based artists, Liang Shuo, was commissioned by M+ to create an installation made with bamboo scaffolding and plastic plants for the Pavilion’s interior courtyard. In the Peak (2019) is as unremarkable as its materials are common in Hong Kong. I realize that bamboo scaffolding is unique to Hong Kong, and I too was amazed the first time that I saw it covering the side of a city building. But here the M+ Pavilion just looks like it is being renovated and someone stuck some plastic flowers and plants in a vain attempt to make it look Instagrammable. Every 15 minutes, only six people (you have to put your name down on a list ahead of time) are allowed into the structure to walk up a few steps and look out a pair of “windows” (gaps in the scaffolding) at views of the The Peak and M+’s new building, which supposedly reference the way landscape is framed in Chinese paintings. In reality, you can see these views from just about anywhere in West Kowloon, in the same way that you can find plastic plants and bamboo scaffolding every time you go out on the street in Hong Kong. In terms of architectural riffs on bamboo scaffolding, Doug and Mike Starn’s Big Bambú projects, built on top of the Met in New York and above the trees in Setouchi and elsewhere, are far more free-form and complex explorations of the materials.

Samson Young’s work, Muted Situation #22: Muted Tchaikovsky’s 5th (2018), which debuted at the Biennale of Sydney in 2018, was shown in the Shanghai Biennale later that year, at Hong Kong’s Visual Arts Centre in March 2019, and won the Prix Ars Electronica in September 2019. It’s a rightfully acclaimed work that is both conceptually and formally powerful; the work is sophisticated but also accessible. To see this orchestra, in complete sincerity, submitting to the physical blockage of their instruments yet nonetheless playing away; to contemplate this gesture’s potential metaphorical meanings in a variety of contexts—from the suppression of marginal communities’ voices, including the denial of LGBTQ rights, to the increasingly normalized repression of free political speech in many contexts, in Hong Kong and elsewhere in the world. We still hear the music despite not hearing the notes, which suggests the paradox inherent in all forms of repression. This is an artwork that in the future people will see as emblematic of this moment, in Hong Kong and the world. Its metaphorical weight shines through because of the clarity of its unifying concept and its precise, powerful realization.

Back in March, I convinced myself that I would have picked Young for the Sigg Prize. But looking at the numbers, I thought again. The winner gets HKD 500,000 (USD 64,500) and the five other shortlisted artists receive HKD 100,000 (USD 12,900). The total prize money is HKD 1 million (USD 129,000). One artist gets half, the others just ten percent. Is Young’s work five times better? Or is Young as an artist five times more deserving, now or in future? Maybe the winners among us, no matter how deserving, don’t need to receive so much more than the rest.

HG Masters is ArtAsiaPacific’s deputy editor and deputy publisher.

The inaugural Sigg Prize exhibition is on view at the M+ Pavilion, Hong Kong, until May 17, 2020.