Shows

Come Inside’s “Baby Shower”

Baby bottles filled with booze welcomed visitors at the opening of artist duo Come Inside’s “Baby Shower” exhibition. An intense glow of pink fluorescent light seeped across the concrete floors of Gallery Exit, concentrated at the far corner of the art space, while music blasted from a single speaker. Mak Ying Tung and Wong Ka Ying, the pair behind Come Inside, eagerly prompted the audience to join in and limbo over a pool of glitter in a carnivalesque performance, which Mak and Wong live-streamed on Facebook.

Together, Mak and Wong use their pseudo “Come Inside” brand and fake pop group personas to critique social norms and gender constructs in Hong Kong, as well as consumer culture’s influence on gender-based merchandise. The pair uses adolescent visuals to parody hyper feminine culture, while appropriating stereotypes to turn them into strengths. Two overlapping hearts with the group’s logo in the middle were emblazoned on various items throughout the exhibition. The symbol was first seen on glass bead curtains—Warm Welcome (2017)—a reference to the decorative partition hung in teen girls’ bedrooms, or even a provocative reference to the entrances of brothels and strip clubs. In the same vein, fluorescent pink lighting reminded viewers of “one-woman brothels” that are prevalent in Hong Kong, marked by pink neon lights above doorways or outside windows.

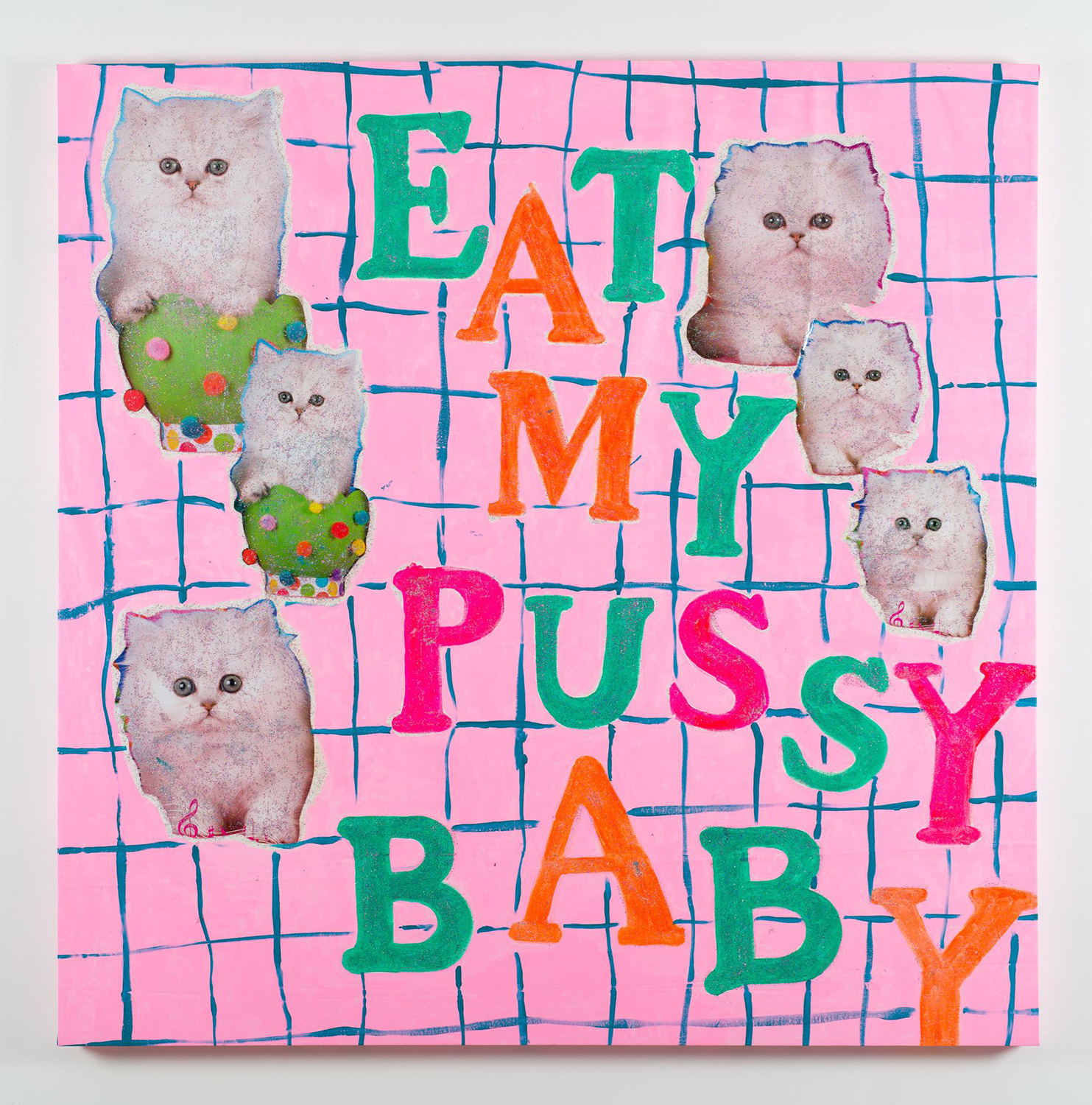

Sexually suggestive slogans mocked traditional feminine ideals and disarmed viewers with crude references portrayed through innocent visuals. Eat My Pussy (2017) is a collage of fluffy white kittens on a pink background, with the message “Eat My Pussy Baby” painted across the canvas in blocky, childish letters. The repetitive combination of imagery reminds us of the prevalence of felines on social media and the ease of sharing multimedia, whether it’s cats or women. The title’s bold language also evokes strong feminist movements of recent times. “Pussy” is a word that is used in rejection of female objectification, and the term has been appropriated by activists for empowerment, including Russian feminist punk band Pussy Riot’s own naming, and in the unmissable presence of “pussyhats”—pink beanies with cat ears knitted or sewed together by protestors—at the global Women’s March protests in January 2017.

The objectification of women is again seen in the video work Snap Like Snow (2017) and an accompanying installation Snap Like Snow Wallpaper (2017). Two flat screen televisions were hung from the ceiling to face each other, as if in conversation via a social media platform. Mak and Wong each appeared on one screen, which looped short clips of them posing with “filters” that transformed the artists into cartoon animals, statues and flowers. Such filters on social media phone apps have come under fire; in 2016, Snapchat was accused of whitewashing, facial slimming and eye enlargement, reinforcing unrealistic beauty ideals consistent with the popularity across Asia of whitening cream, facial slimming gadgets and contact lenses that give the illusion of wider eyes. Come Inside’s installation behind the videos—their “wallpaper”—was a collection of 800 A4-sized printouts of the various images with digital alterations. These particular social media images, by design, are meant to disappear after the first viewing. The pair’s physical documentation comments on the misuse of apps like Snow and Snapchat. These apps have been used for “sexting,” but some recipients of explicit images through such channels have taken screenshots in breach of the senders’ trust. Certain cases even involved underage teenagers and child pornography charges. The haphazard way in which Come Inside adhered printouts to the wall drove home their message that we misuse the tools we acquire, like Snapchat and Snow, while reminding viewers of the idolization of pop stars and celebrities—figures whom we also see through carefully polished “filters” created by image consultants or marketing experts.

The strong visual thread of glitter and the pink color tied together the show, with strong feminist and anti-consumerism messages. Many works were easily dissected with leading titles, with no mysteries for the viewer to divine. And yet, there was a social consciousness embedded in the creations of Come Inside, as seen in their use of branding techniques and appropriated visual vocabulary. Loud but subversive, Come Inside playfully bring to light an awareness of a deeper issue rarely discussed with such openness in conservative Hong Kong.

Come Inside’s “Baby Shower” is on view at Gallery Exit, Hong Kong, until March 15, 2017.

Katherine Volk is assistant editor at ArtAsiaPacific.