Shows

Cinema of Subversion: Asian Avant-Garde Film Festival

Asian Avant-Garde Film Festival

M+

Hong Kong

May 30–June 2

The French poet and avant-garde filmmaker Jean Cocteau once remarked that “a work of art should be an object difficult to pick up . . . It should be made of such a shape that people don’t know which way to hold it, which embarrasses and irritates the critics, incites them to be rude, but keeps it fresh.” Cocteau was a provocateur who was wary of intellectuals and preferred to be classed as an amateur craftsman. Like his surrealist counterparts, Buñuel and Dali, Cocteau was drawn to dark spaces, passageways, reflective objects, and body parts. In his oneiric first film, The Blood of a Poet (1932), a man creeps down the corridor of a hotel and peeps through the keyholes of various doors (an apt metaphor for cinema and the cinema-goer as voyeur) only to discover what Cocteau later described as “documentary scenes of another kingdom.”

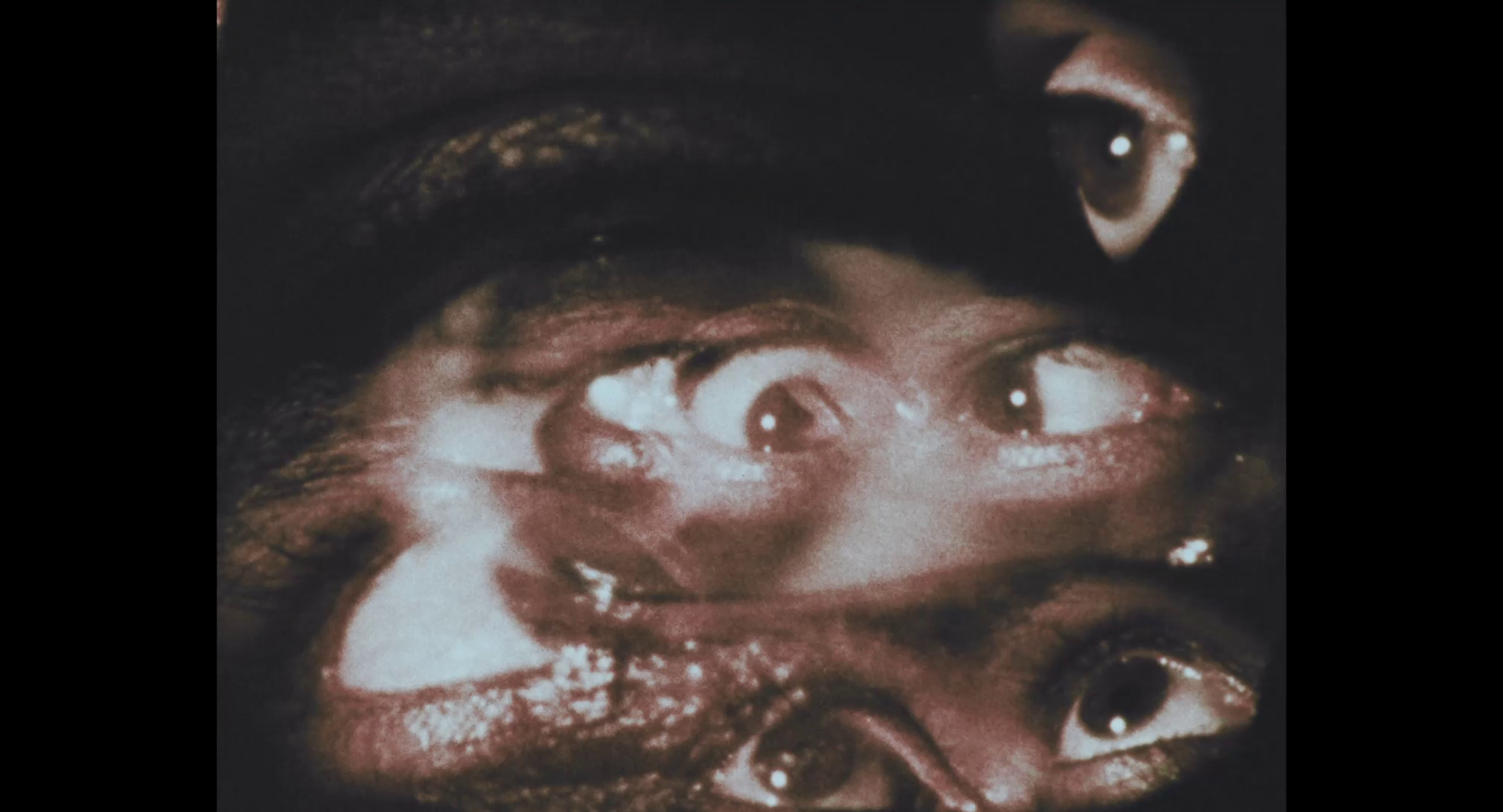

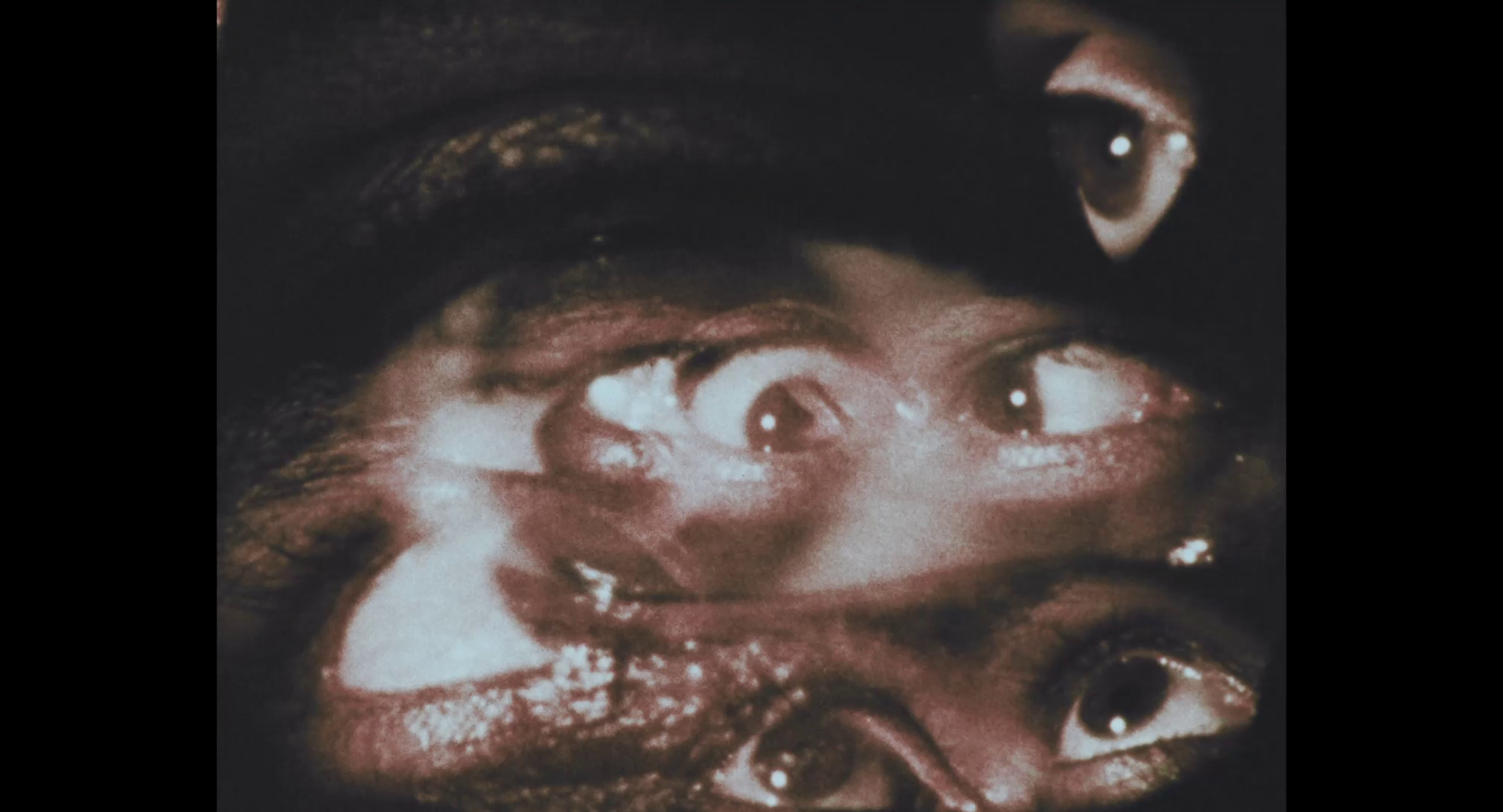

At this year’s inaugural Asian Avant-Garde Film Festival at M+ in Hong Kong more than 60 films spanning six decades were screened over four days. One of the first programs, “Self x Society,” included an early work, Eyes (1968), by one of Singapore’s pioneering experimental filmmakers, Rajendra Gour. Shot on 16mm, Eyes is an exploration of mankind’s capacity for violence and our immunity toward images of suffering. By juxtaposing archival footage of unidentified wars and conflicts with kaleidoscopic images of eyes staring into the lens (reminiscent of the eye staring back at the camera in Cocteau’s The Blood of a Poet), Gour implicates the viewer, turning them into an active participant.

From images of dead, wounded, and starving bodies to five men in red hoods, black blindfolds, and bandaged feet, accompanied by the sound of a steady drumbeat. In 1983, Chen Chieh-jen took to the streets with a group of friends in an act of defiance against the authoritarian Kuomintang-led regime in Taiwan. Chen first conceived of Dysfunction No.3 (1983) during his time in the military as a way of regaining autonomy over his body, which he felt he was beginning to lose possession of under the powers of state control. A decade earlier, in South Korea, a group of radical young feminists from the prestigious Ewha Womans University formed the Kaidu Club, an experimental filmmaking collective led by Han Ok-hee determined to defy conventions in an industry dominated by men. One of Han’s first films to break the mold was The Hole (1974). Shot on stark black-and-white 8mm film, it opens with fragments of paintings by Kaidu’s co-founding member, Kim Jeomson, followed by a hand reaching out of an opening in the ground. With its dynamic camerawork and eclectic style, Han’s early foray into experimental filmmaking is an emphatic expression of the desire for freedom and escape in a repressive, patriarchal society.

In a 1968 article in the French film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma, Jacques Rivette wrote that some films he had seen were depressingly comfortable: not only did they change nothing, but they made the audience who saw them happy with themselves. He believed that the role of cinema was to disturb, contradict ready-made ideas, and to provoke discomfort. In the Philippines, a 14-year period of one-man rule by Ferdinand Marcos, beginning in 1972, spurred a creative force of oppositional cinema that took on many of Rivette’s ideas, with filmmaker and historian Nick Deocampo part of what is considered to be the Second Golden Age of Philippine cinema. “Slivers of Desire,” co-curated by Deocampo, featured three short films made in and around the time of the Marcos dictatorship. Deocampo’s Oliver (1983) documents the daily life of Reynaldo Villarama, a 24-year-old entertainer who performs in the gay nightclubs of Manila to support his family. The film begins with an unadorned Villarama applying make-up and putting on a golden leotard before performing a version of Liza Minnelli’s Cabaret on stage. Throughout the film, Villarama gives candid accounts of his life both through voice-over and by talking directly to the camera. He details the sudden death of his mother, the disappearance of his father, his upbringing in an orphanage, and a subsequent experience of receiving 500 pesos to appear in “a movie shot in a hotel room” at the age of 15. Halfway into the film, Deocampo follows Villarama through the streets of Manila: “this is where we used to live,” Villarama says, looking at an empty vista full of rubble. “I am thinking . . . I am watching my own city, thinking about my life and asking myself, what is my future?” Oliver is as much a portrait of one person as it is a portrait of a place in an era marked by oppression and socio-political upheaval. The film ends with one of Villarama’s shows, which he proudly calls Spiderman. In it, Villarama pulls close to 100 meters of thread out of his anus as he meticulously builds a web on stage, bringing to mind Carolee Schneemann’s subversive performance piece Interior Scroll (1975).

.jpg)

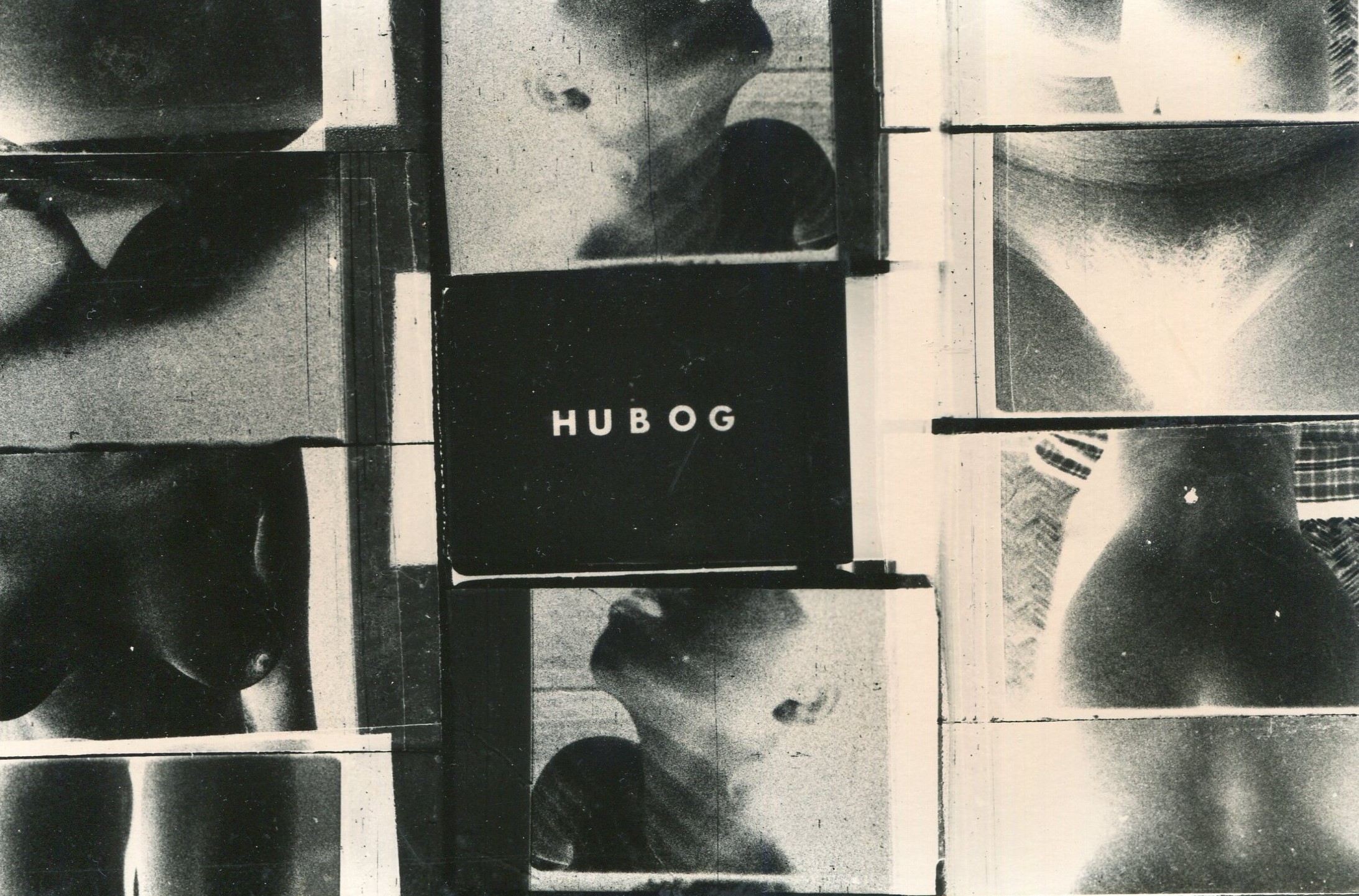

The second film to screen in Deocampo’s program was made during the height of the People Power Revolution in the Philippines. Juan Gapang (Johnny Crawl) (1987) by Roxlee features a cartoonish man with long black hair covered in white paint crawling through the streets of Manila at a jittery pace in an act of civil disobedience. The People Power Revolution only lasted three days but, remarkably, it led to the departure of Ferdinand Marcos and paved the way for the restitution of democracy in the country. The final film, Victoria Donato’s Hubog (1989), was made in the wake of Marcos’s disposal. Juxtaposing images of Catholic iconography with found footage of bare breasts, butt cheeks, and vaginas, followed by a woman beckoning a man with her carefully manicured finger and, finally, in pornographic detail, a close-up of a man penetrating a woman, Hubog challenges what feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey termed “the male gaze,” and places the female body in a position of power. Mulvey’s term echoes the late experimental filmmaker Maya Deren, who insisted in a seminal essay on amateurism that “the most important part of your equipment is yourself: your mobile body, your imaginative mind, and your freedom to use both.”

Meanwhile, the program “Yam & Yang: Experimentations in 16mm” was less concerned with the erotics of the body and more interested in bodies in various states of neglect. Hong Kong-born American filmmaker Ruby Yang and her husband Lambert Yam first met at a film screening during their time at the San Francisco Art Institute in the 1970s. Ruby was studying painting, but Lambert convinced her to start making films. The program presented five of their films, starting with I Am the Master of My Boat (1976) by Lambert Yam, an impressionistic essay film documenting San Francisco’s bachelor society in Chinatown. Yam went to the United States in search of a better life, but soon after arriving he was surprised to find so many lonely, old men and expressed the need to make the film in order to control his own destiny. “They looked like they were just . . . waiting to die,” Yam told the audience in a post-screening talk. Beautifully shot on 16mm film, I Am the Master of My Boat cross-cuts figures of solitary men with the image of a row boat in motion. Ruby Yang’s Mirror Points (1982), meanwhile, was made during her final year at the San Francisco Art Institute by a crew of just two, with Yang acting and Yam serving as cinematographer. Mirror Points is an expressionistic exploration of a young woman overcome by fear and angst. After seeing the film again after so many years Yang recoiled, admitting, “it seems so dated.” But on the contrary, the films of Yam and Yang, especially screened in their original 16mm format, appear timeless.

The eclectic array of films shown during the AAGFF exemplified the avant-garde spirit and the festival was able to showcase lesser-known moving-image works from across the region, many of which have not been widely screened in Hong Kong before. But with over 60 films (plus additional side events including tarot readings, live performances, and screen-printing workshops) it was, at times, too wide-ranging, lacking a cohesive vision and intent. In an interview with Vogue HK, lead curator of moving image at M+, Silke Schmickl, even admitted that one of the incentives behind the festival was not only to share works from their existing collection but to acquire new ones, begging the question: who was the festival really for? Besides, doesn’t the notion of the art museum as a public institution contradict everything the avant-garde stands for? Whether it was the Dadaist movement known as Cinéma Pur, the Blue Group (Ao no Kai) in Japan, or the Kaidu Club in South Korea, avant-garde filmmakers have never ceased to break convention. Existing on the periphery, along with their films, they refuse to conform to industry standards, whether institutional or commercial. They are inherently anti-establishment, unconcerned with box office success or public taste. So how can a museum like M+ push their own boundaries rather than simply showcase the works of others who dared to? And how might the museum play a more proactive, central role in generating rigorous discourse on the state of independent cinema and help foster a new generation of avant-garde filmmakers in Hong Kong?

Frances James is an independent filmmaker and writer based in Hong Kong.