Shows

China, Four Ways: Pretense and Propaganda in Venice

While many fret over China’s tightening grip on Hong Kong and its clear intention to one day reclaim Taiwan, the Venice Biennale has long operated on a “divide and placate” policy by hosting four pavilions. There is one official China Pavilion in the Arsenale and three collateral exhibitions mounted by art museums in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macao. This year, given that the Biennale’s overall theme is how to define and relate to “foreigners,” the differences between these Chinese subdivisions are revelatory, ranging from officious nationalism projected by the leviathan PRC to escapist reverie from the tiny peninsula of Macao.

PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA: “ATLAS: HARMONY IN DIVERSITY”

“Atlas: Harmony in Diversity,” the title of the official China Pavilion organized by the China Arts and Entertainment Group, sounds very much on trend for this ultra-politically-correct Biennale, wherein Indigenous groups and factions of the LGBTQ+ community unite to rewrite history through art. The locution is even surprisingly democratic in tenor. (Where have we heard e pluribus unum before?) The organizing concept, we’re told in a tabloid accompanying the show, is—like everything else in the PRC pavilion—steeped in Chinese tradition. The ancient Chinese character for “atlas” evokes three birds in a tree and can be used not only as a noun but also as a verb meaning “gather.” Meanwhile “harmony” is a long-established principle in China and throughout East Asia, designating cosmological, social, and individual orderliness and well-being. The fact that this venerable term has now been repurposed to serve absolute one-party rule goes unmentioned.

Such theorizing doesn’t matter much anyway, since the lynchpin of the purported curatorial agenda, “diversity,” is notably missing. If any of the seven artists hail from one of China’s 55 ethnic minority groups, they remain unidentified. And forget any hint of passionate personal expression. (For that, one might check out the emotive painterliness in a rambling satellite solo by market darling Zeng Fanzhi.) In the national pavilion, none of the works have even a strong regional character; instead, they all reinforce a highly idealized vision of “Eternal China,” a mythic land of happy villagers, prosperous merchants, esteemed poets and painters, and benevolent emperors. It’s a Golden Age fable proselytized through a very current, very active ideological apparatus. Like the pavilion’s two curators, professors Wang Xiaosong and Jiang Jun, six out of the seven “Atlas” artists are full-time academics who also hold supervising positions in the cultural bureaucracy. Chinese universities and arts agencies are, Western readers should be advised, anything but hotbeds of social critique. Indeed, one of their main administrative directives these days is to intellectually enhance the patriotic legend of Eternal China.

This exhibition’s tone of proud, though wounded, nativism (weirdly in keeping with artistic director Adriano Pedrosa’s postcolonial Biennale mandate) is set by an expansive array of vitrines containing pictures of 100 classic Chinese paintings currently held abroad. This is the case, the tabloid tells us, with one-fourth of the 12,405 works listed in the Comprehensive Collection of Ancient Chinese Paintings, a digital project by Zhejiang University (where, not coincidentally, curator Wang Xiaosong is dean) and the Zhejiang Provincial Administration of Cultural Heritage. Hanging in the air, unacknowledged, is the implication that these historical treasures should never have left China—presumably they were either plundered militarily or else extracted through unfair bargains when Chinese sellers were under financial duress—and ought now to be repatriated, whether through diplomacy, shaming, or targeted repurchase. Or maybe world conquest.

The animating spirit of a misty once-and-future China pervades all the contemporary elements of the exhibition. Zhu Jinshi, the only non-professor in the group, contributes Rice Paper Pagoda (2024), a rectilinear tower of rice paper sheets meant to evoke a pagoda, although—illuminated from within—it looks more like a modern apartment block. Meanwhile there is Jiao Xingtao’s flexible copper statues portraying warriors, dancers, sages, and other stereotypical characters from the past, titled Soul Rhyme (2022). And Shi Hui presents Writing Non-Writing (2021–24), a huge panel of knots resembling Chinese characters, along with blocky forms festooned with markings that imitate writing without in fact being writing (a device that Korea’s late Park Seo-Bo explored for decades in his Écriture series). The inscriptions illustrate instead eight brushwork techniques common to both calligraphy and ink painting.

.jpg)

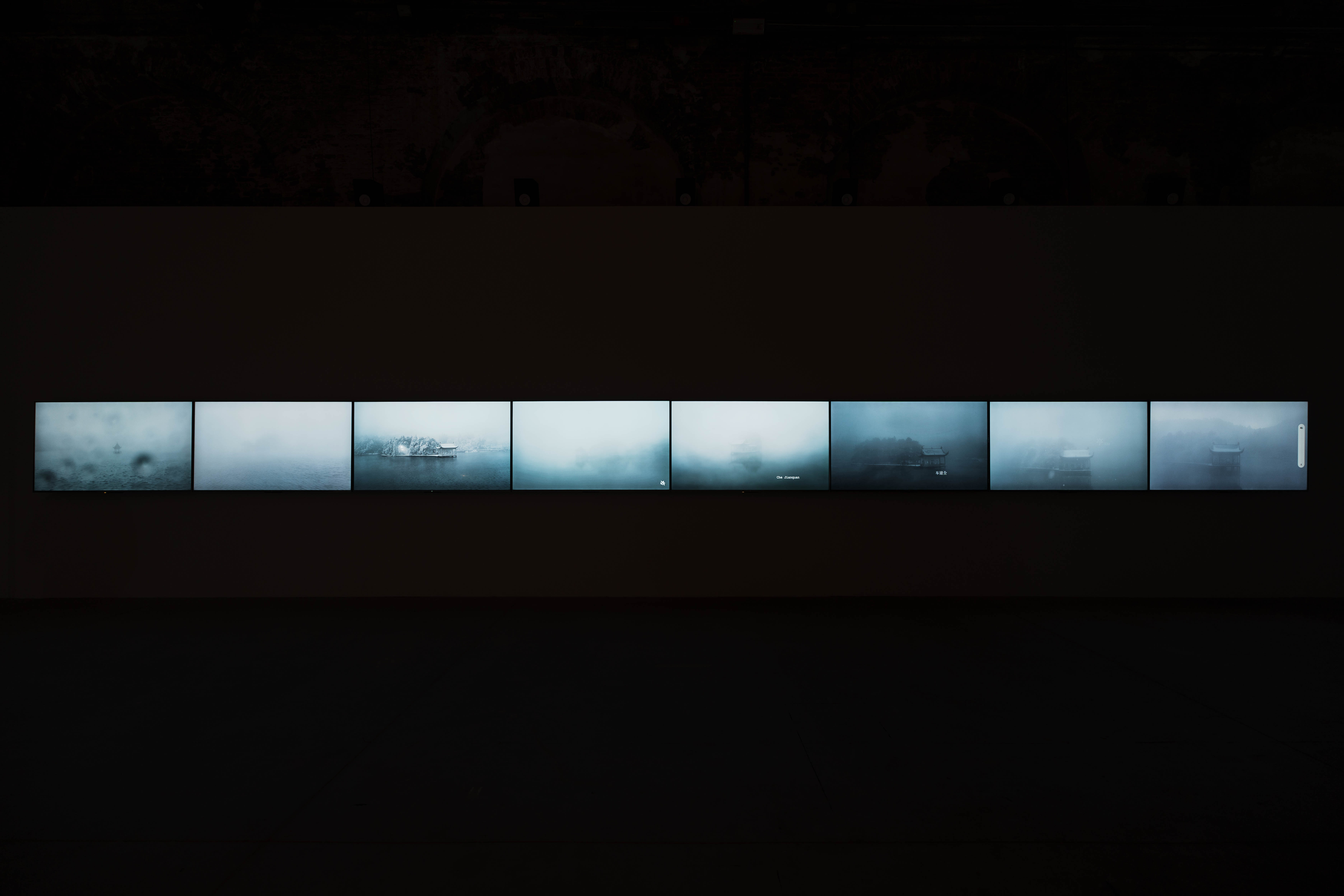

Fading sequentially in and out on a row of wall-mounted video monitors are 20 shots of the same ancient lakeside pavilion (hence the work’s title, Pavilions), viewed in various weather and lighting conditions from 2002 to 2023 by photographer Che Jianquan. (Monet’s cathedrals, haystacks, and rock formations, anyone?) Wang Shaoqiang’s Heritage Reimagined (2024) is a massive grid of 105 paintings purportedly demonstrating formal resonances between many modern Western painting methods and those of the Song Dynasty. Outdoors, Qiu Zhenzhong offers two large openwork sculptures from the Status series (2024) that visualize calligraphic strokes in three dimensions, while encouraging an in-and-out rapport with the surrounding garden—another longstanding Chinese conceit. Wang Zhenghong’s Symphony of Birds (2023) not only sends performers wearing bird ornaments through the pavilion from time to time, but also gives visitors the chance to take away a stylized bird-shape lapel pin for free—or rather, as “free” is routinely understood in the age of data harvesting, in exchange for one’s name, age, nationality, email address, and phone number.

Overall, the viewing experience of “Atlas: Harmony in Diversity,” leaves one mildly agog, yet again, at the irony of the Chinese Communist Party, which previously spent three decades systematically trying to destroy China’s “feudal” heritage, and is now championing that same refined cultural legacy as a soft-power way to win hearts and minds within China and across the globe. Such a major “course correction” (as the cadres call life-and-death policy shifts affecting millions), might be truly commendable, if its underlying purpose were not culture-washing.

YUAN GOANG-MING: EVERYDAY WAR

TAIPEI FINE ARTS MUSEUM

No place on Earth has greater concern about China’s future plans than Taiwan. The island’s status has been in dispute ever since Chiang Kai-shek and two million defeated Nationalists fled there in 1949, bringing along much of China’s national treasury and an enormous hoard of its most valuable cultural artifacts. For four generations now, residents of Taiwan have conducted their daily lives under continuous threat of invasion. So it’s little wonder that an anxious atmosphere pervades the Taiwan collateral exhibition this year. “Everyday War,” naming an all-too-familiar condition, features videos and installations by midcareer artist Yuan Goang-Ming, cannily selected and displayed by US-based curator Abby Chen.

In a space that reflects the stone building’s past history as a prison, the Palazzo delle Prigionione, a large, centrally located screen is filled with drone-flyover shots of Taipei streets, eerily devoid of both pedestrians and moving vehicles during the city’s annual Wanan Air Defense Drill. A neighboring screen shows members of the Sunflower Student Movement occupying the legislature in 2014 in order to block passage of the Cross-Straight Service Trade Agreement, which would have liberalized commerce between Taiwan and the mainland. In two alcoves, visitors can sit facing videos of rooms in comfortable middle-class apartments. The views linger like subliminal real-estate ads until the rooms are suddenly torn apart by heavy gunfire or a missile-strike explosion, bringing war home wherever you live. A real table elaborately set for dinner is presided over by a video that merges street views from all over the world into a seamless loop. From time to time, the table shakes as though from the rumble of approaching tanks.

The “Everyday War” experience is at once timeless and topical. From Priam’s household anticipating utter destruction at the hands of marauding Greeks in the Iliad to the Cold War’s thermonuclear “age of anxiety” to the latest fear and loathing in Gaza and Ukraine, the world has never lacked for apocalyptic terror. Yuan’s deft move is to make that dread as intimate as the breath of a stealthy intruder on the back of one’s neck.

TREVOR YEUNG: COURTYARD OF ATTACHMENTS

M+, HONG KONG ARTS DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL

Does looking at an empty fish tank make you think of love? If not, you’re the wrong kind of viewer for Trevor Yeung’s “Courtyard of Attachments: Hong Kong in Venice,” an exhibition that requires viewers to make conceptual connections that the artist is unwilling to realize formally—in other words, it’s a very typical 21st-century art show.

The indoor portion occupying several rooms is fish tanks all the way through. The entryway sets the motif with two fully tricked-out aquariums, sporting rocks, plants, gravel, purifiers, and even algae—everything except fish. This absence is undoubtedly meant to make us think. But about what, there is no clue. The future of our polluted, over-fished oceans, perhaps? If so, what are we to make of the nearby set of five colored spheres in a vitrine? The room’s deadpan arrangement of objects could signify just about anything.

.jpg)

Since the same is true in every room that follows. The artist’s father owned a seafood restaurant, and small floating decorations “are considered auspicious and are common decorative elements in Chinese businesses,” according to the brochure text written by curator Olivia Chow. In subsequent chambers we encounter hanging plastic bags of the sort that pet-store fish are displayed in. One of them appears broken in a large-printed photograph and supposedly alludes to “the consequences that arise when our innermost desires override thoughtful consideration.” Was the plastic bag dropped by someone with an inner compulsion to see a goldfish flounder on the sidewalk? Confronting a couple of stacked wooden plant stools holding up a fish tank whose water is whipped into a whirlpool (mislabeled a “tornado” in the work’s title, Little Comfy Tornado [2024]), we are told that “the seemingly excessive support mechanism evokes a sense of unease and invites consideration of the bureaucratic heaviness that often undergirds the simplest actions in a social system.” A social system in a swirling vat of water? Is that what comes to mind when one looks at these things? Why should those particular socially conscious associations arise from the dark lagoon of the human psyche?

.jpg)

The installation in the final room, titled Cave of Avoidance (Not Yours) (2024), fills the space with rack after rack of fully equipped aquariums under purple fluorescent lights—and might induce some disconcertingly undoctrinaire, even purely aesthetic, thoughts. Initially, it can be hard to see how in the solipsistic game of “guess what x means to me [the artist or curator]” this installation is really all about social conscientiousness and “care.” Shouldn’t we expect “care” to yield aquariums full of diverse, healthy creatures? Or an exhibition that intrigues and enlightens rather than willfully baffles viewers? Fortunately, though, not all hope is lost. Set in a fish-breeding pool in the courtyard is a fountain Yeung designed to purify Venetian canal water and return it to the system. For once, the physical artwork bears a plausible connection to its message: “the possibility of rebirth in spite of the ceaseless exhaustion of resources.”

My first thoughts upon exiting the Hong Kong pavilion: Imagine living in a world where the significance of a pietà depends not on the worldview embodied in the figures, and not on the passion, intelligence, and skill of the artist, but instead on knowing the vocation of the sculptor’s father. (Never mind; you already live in such a world.) My second thought: Why are Hong Kong’s shows at Venice—think of those by Lee Kit, Samson Young, Shirley Tse—so often oblique and understated? It could be a signature M+ style, since the museum has coordinated the city’s last six presentations at the Biennale. Or it could be a deliberate riposte to the mainland’s cultural bluster. In some ways it also feels like denial of coming to terms with the fate looming daily closer for Hong Kong. A decade after the Umbrella Movement, the arrest of booksellers and independent publishers, and the travel restrictions imposed during the Covid-19 pandemic, there are artists in the city whose practice responds vividly to the political climate change, but can the selection committee for the Hong Kong pavilion nominate artists who overtly discuss these inconvenient truths?

WONG WENG CHEONG: ABOVE ZOBEIDE

MACAO MUSEUM OF ART

People are also absent from the mythic landscape evoked by Wong Weng Cheong in “Above Zobeide,” the exhibition organized by the Macao Museum of Art for the Venice Biennale. The title refers to one of Italo Calvino’s “invisible cities,” designed by men who shared the dream of pursuing a beautiful naked woman through the streets. One might assume then that the exhibition surveils, from an aerial viewpoint, the glories and horrors of human sexual desire. One would be wrong.

Instead, continuing a project he has worked on for six years now, Wong has constructed an immersive diorama inhabited by what curator Chang Chan calls “mutant herbivores”—sculptural creatures resembling sheep, rabbits, and deer with radically elongated legs. Given that most of the vegetation in their craggy landscape is at grass or shrub level, it is hard to imagine how these stilt-like appendages convey an evolutionary advantage. But then again, logic is not the determining principle here. In the realm of contemporary art-thought and curator-speak, as we saw in the Hong Kong collateral pavilions, “free” associations reign supreme (bordering on the point of the arbitrary). Thus Wong’s fantasy land supposedly exemplifies “the tight bond between civilization and mutation,” even though only a few incidental vestiges of civil society—an abandoned tower, for example—are anywhere to be seen. Fortunately, the artist himself was a bit more grounded in his April 16 online comments for Macao Magazine. Wong explained the animals ingest grassy nourishment that makes their legs grow to the point where they can no longer reach the grass—a metaphor for rampant consumerism. Given that Macao’s real-life economy is built on casino gambling, the mutants are a fair—or at least understandable—satiric trope. One waits for Wong to link obsessive consumption to dreamy lust, but he never does.

The other major part of the exhibition, a wall of video screens showing visitors as they wander through the installation, clues us into the critical paradigm implicit Wong’s project. “Above Zobeide” reflects a current “progressive” belief that—given human beings’ ecological depredations and their inability to attain social justice, let alone personal moral perfection—the Earth would be better off without us. Somehow, that judgment always seem to allow for one exception: the artist’s own blameless consciousness hovering magically “above” the karmic posthuman spectacle.

Richard Vine is the former managing editor of Art in America.