Shows

Channeling the Grotesque in Mire Lee’s “Open Wound”

Mire Lee

Open Wound

Tate Modern

London

Oct 8–Mar 16, 2025

To coincide with Frieze London, Tate Modern unveiled its ninth Hyundai Commission, titled Open Wound, a visceral, large-scale, site-specific installation that filled Tate Modern’s 3,400-square-meter Turbine Hall. And of course it didn’t take long for the critics to descend, many of whom had at least something to say about South Korean artist Mire Lee’s “grotesque” reflection of the building’s original function as an oil-fueled power station.

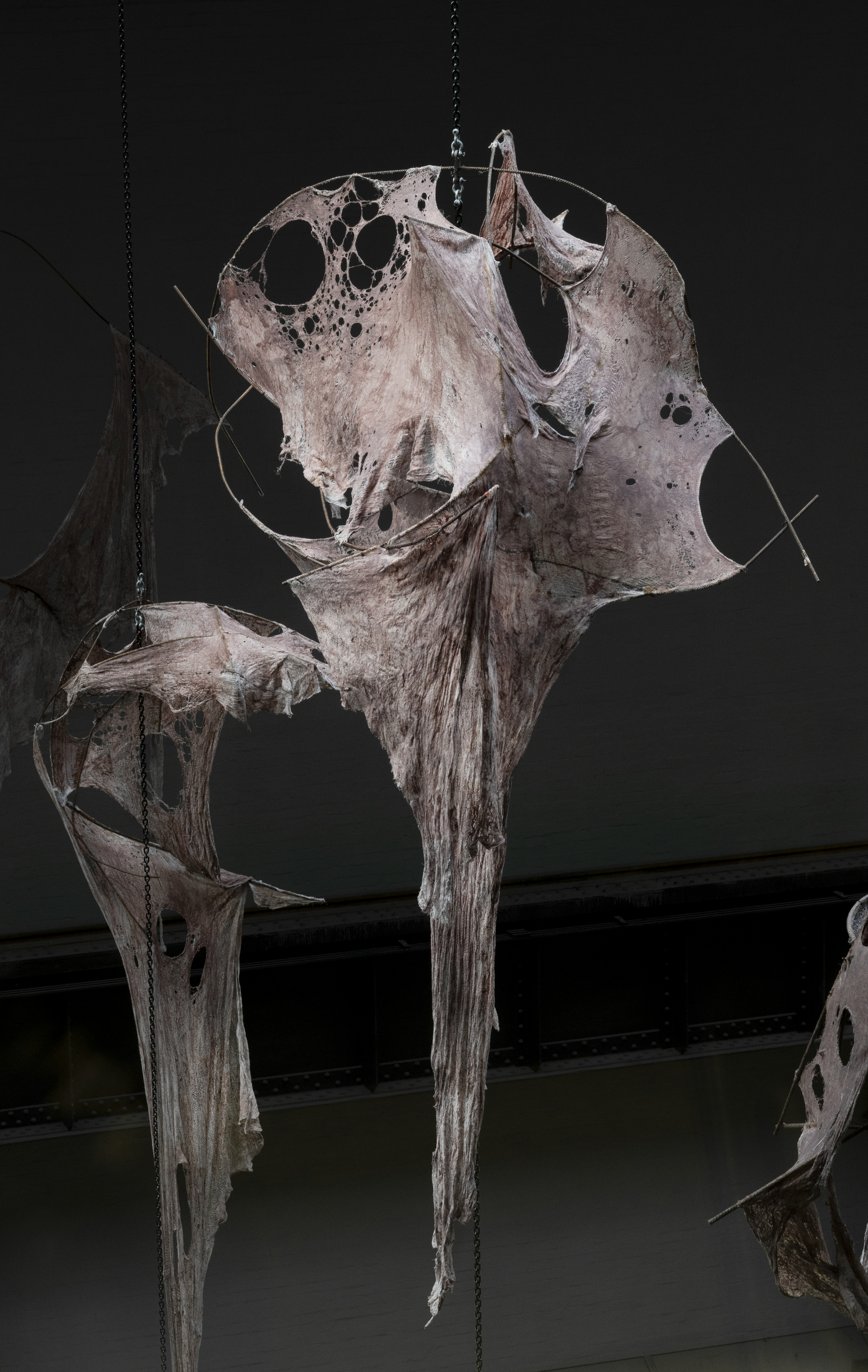

Regarding the cavernous space as an analog for the inside of the human body, Open Wound was Lee’s personal reflection on the relationship between humans and machines by way of her signature aesthetic of juxtaposing the hardness and coldness of industrial components with the softness of fabric. Utilizing over 50 metal chains, Lee created a steampunk environment filled with hanging membranous sculptures she calls “skins.” The nucleus of the constantly evolving installation was situated toward the far east end of the space, where a refurbished turbine had been set in motion, slowly spinning, pumping dark viscous pink liquid through vein-like silicone tubes, before the liquid collected in a large tray underneath. This liquid was then used to dye the skins, which were finally hung together in a structure reminiscent of a large, industrial construction site. The dye gave them a peculiar flesh-like visage, and, once ready, the fabrics were periodically suspended, gradually filling up the grand exhibition venue.

%202.jpg)

Installation view of MIRE LEE’s Open Wound, 2024, seven-meter-long motorized turbine, steel, cement, silicone, oil, clay, dimensions variable, at Tate Modern, London. Photo by Oliver Cowling with Lucy Green. Courtesy Tate Modern.

%20(1).jpeg)

Installation view of MIRE LEE’s Open Wound, 2024, seven-meter-long motorized turbine, steel, cement, silicone, oil, clay, dimensions variable, at the Tate Modern, London. Photo by Oliver Cowling with Lucy Green. Courtesy Tate Modern.

At first glance, Lee’s work was frightening, and reminiscent of dystopian fiction that speculates on a future in which the organic and the machine fuse—symptoms of a certain decay in our society, of Promethean dreams being ignited by too much hubris. This creeping feeling was emphasized by the sound of the rotating turbine, and the drops of liquid amassing in flesh-like pond. Fear and disorientation are nevertheless part of the various degrees of emotional responses that Lee constantly aims to evoke in her audience. According to the press release, Open Wound is “intended to have an unsettling effect on the viewer, evoking a range of contradictory emotions including feelings of tenderness and empathy, as well as melancholy, awe, and disgust.”

Setting aside one’s own immediate response and reaction, there was arguably a deeper reflection to be made on the relationship between this site, its resonances, and the intriguing ability of contemporary art to connect historical perspectives to the speculative possibilities of wider narratives concerning our present and our future. At the time of construction, the Turbine Hall was the heart of what was then known as Bankside Power Station, designed in 1947 by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott as a response to the increasing demand for electricity in the city. With a monumental style mimicking a “cathedral of power,” the building embodied the ethos (whether real or imagined) of modernity, and represented forward-thinking values that at that time were informing and reshaping urban life, as well as, more specifically, the architectural development of the city following the second Industrial Revolution. In Charles Dickens’s novel Hard Times (1854), the British author describes industrialization as a process that turns individuals into machines, hinting not only at conditions of labor, but at the rise of capitalism as the de facto socioeconomic framework. Contemplating the chain of production in Lee’s visceral and mechanical installation—which is open and festering, like a wound—created a connection between a difficult past and an uncertain future. The question is: are we still at a threshold, or are we facing a point of no return?