Shows

Caraballo-Farman’s “Overcoming Pink Fatigue”

For their first solo exhibition at Ramis Barquet Gallery, the artist duo caraballo-farman presented works from their project “Object Breast Cancer,” begun during a 2010 Guggenheim Fellowship and Eyebeam Residency. This exhibition arises from Leonor Caraballo’s personal battle with breast cancer. After undergoing surgery to remove the cancer, Caraballo and her partner Abou Farman decided to demystify this disease, which is typically represented in breast cancer awareness campaigns only by a pink ribbon. Moreover, the overuse of this ribbon has arguably caused “pink fatigue,” leaving people desensitized to its symbolic content.

On opening night, a 14-year-old girl sat at a wooden table responding to guests in Latin while making stencil rubbings with lead pencil on paper, through which appeared the words “life time risk,” back to front. The girl’s identical twin eventually appeared from a backroom to exchange roles, creating an uncanny moment in which to contemplate youth, life and death. This performance, The Chances of This Happening (2011), contrasted life’s unpredictability with the persistent human desire to know its outcome, including attempts to prognosticate the health risks of modern lifestyles.

Such issues set the tone of the exhibition, which was divided among the three rooms of the gallery. The back room focused on “resonance” as the first act by which images of the internal body are created, either by medical MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scans, or by shaman “extractions”—the removal from the body of energies that do not belong. All images in the show relate to these techniques, both of which Caraballo utilized in her own treatment. At first, the duo referenced Caraballo’s own MRI scans, but later included those of friends and fellow patients. The nearly identical installations, Resonance (Light 1) and Resonance (Light 2) (both 2011) feature glowing cancerous forms mounted on the wall with accompanying headsets playing sounds of either the magnetic resonance of MRI scans or the acoustic resonance of shaman chants, emphasizing their unlikely similarities. Though created by different techniques, these audio frequencies were used to produce images in a similar way, either as objects printed by rapid prototyping machines or anthropomorphic depictions.

Caraballo-farman’s visual investigation of tumors continued in the middle room, which examined the growth of self-replicating malignant cells. According to the artists, these unseen malignancies in fact conjure no particular image for most people, further explaining their motivation to accurately and metaphorically visualize such diseases. For Extractions (No Shrink Silicon Mold Terrain) (2011), the duo created 36 pink silicone molds from one cancerous shape, mimicking the multiplication of cancer cells. This also questions the reproduction of art, as the mold becomes the copy while the figure is the original object. The pink casts are then slashed, referencing the cuts of a surgical knife in the skin. In this way, the inner room is comparable to the internal space of the body where the alien matter is first discovered; the middle room is the intermediate space, functioning like skin to the body; while the main room is the space outside the body, where the cancerous forms are freestanding, as in the “Extractions” series (2011).

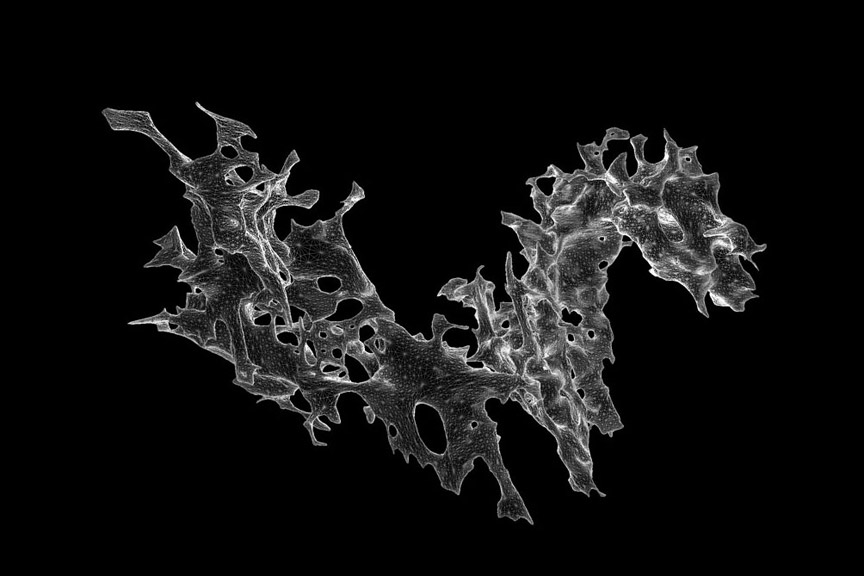

Consisting of eight different cancers cast in bronze, using the traditional lost-wax technique, “Extractions” reproduces exact details of the erratic forms that have been removed from the body. By refusing to identify the “owner” of each tumor, Caraballo detaches their personal stories, instead focusing on their abstract form. Nearby, these same shapes are digitally rendered using 3D computer imaging software, as topographical wire mesh shapes, printed on thick vinyl in the “Cacinodaimons” series (2011). Here, the artists connect the anthropomorphic constructions captured by MRI with the energies that a shaman is said to locate and remove during the extraction procedure. The resulting prints are named after animals the shapes resemble, such as the dragon in Carconodaimon Dracon (2011).

Caraballo-farman’s investigation of cancer’s image and subsequent reworking of its form, using a variety of representational techniques, functions as a kind of treatment, allowing the artists to deal with the experience of cancer both physically and emotionally. These images and sculptures are intended to heal others by allowing viewers to confront the usually unseen forms directly, rather than losing sight of what cancer actually constitutes through such readily consumable images as the popular pink ribbon.