Shows

“Avant-Garde Shanghai”

The group show “Avant-Garde Shanghai” revealed the glut of activity taking place in Shanghai post-Cultural Revolution. Two sections contrasted individual practices with information about the genesis of events and presentations. These revealed two factions: those in conformity with the dominant narrative around the ’85 New Wave movement and Beijing’s seminal “China/Avant-Garde” exhibition in 1989, eager to blur Chinese and Western styles and ideologies; and artists who privileged the autonomous development of contemporary Chinese art as an instrument of socialism.

Painted works showed an enthusiastic mix of China’s traditions with new, foreign idioms. Several artists, such as Chen Xinmao, straightforwardly combined traditional ink painting with global influences, as in Portrait as a Landscape (1987), which features tangled fibrous materials and blobs of gesso redolent of Marcos Grigorian or Alberto Burri’s style, over gestures in ink. Some artists used traditional materials and mediums—xuan paper and Hui ink—to render abstract expressionist marks, while others, such as Mao Xuhui and Yuan Shun, referenced Pop Art, layering ink painting with pasted-on photocopies and printed forms. The impact of European art was also apparent in oil paintings, such as the stylized portraits of Lin Lin and in Gong Jianqing’s abstractions, thickly painted in fiery colors. These recalled the aesthetics of contemporaneous neo-expressionists, such as the German Mülheimer Freiheit Group.

The opposing tendency, to critique modern art as a perverse influence—seen as corrupting the young and attacking the natural—was suggested by Apple Interpretation (1991), a performance-video-installation by Zhang Long, Zhu Dake, Zhang Xian, Zhou Hua and Chen Liwei. In the video, a succession of artists take fruit from a rectangular arrangement, sculpting them with basic tools and daubing them with paint, before replacing them in their original position. In the show, the monitor screening this sequence was installed above a vitrine containing real apples. These fruits were red and flawless, but the fruits in the video are green and blemished—in Chinese, the character qing designates nature’s green colour and youth, while hong, meaning red, also means revolutionary. The juxtaposition suggests many readings, one being that the making of “modern” abstract sculpture from apples in the video is antithetical to nature. A second interpretation directly references the liberation of society at the time: peace is a homonym for the Chinese word for apple, and thus the unaffected red apples connote a certain harmony.

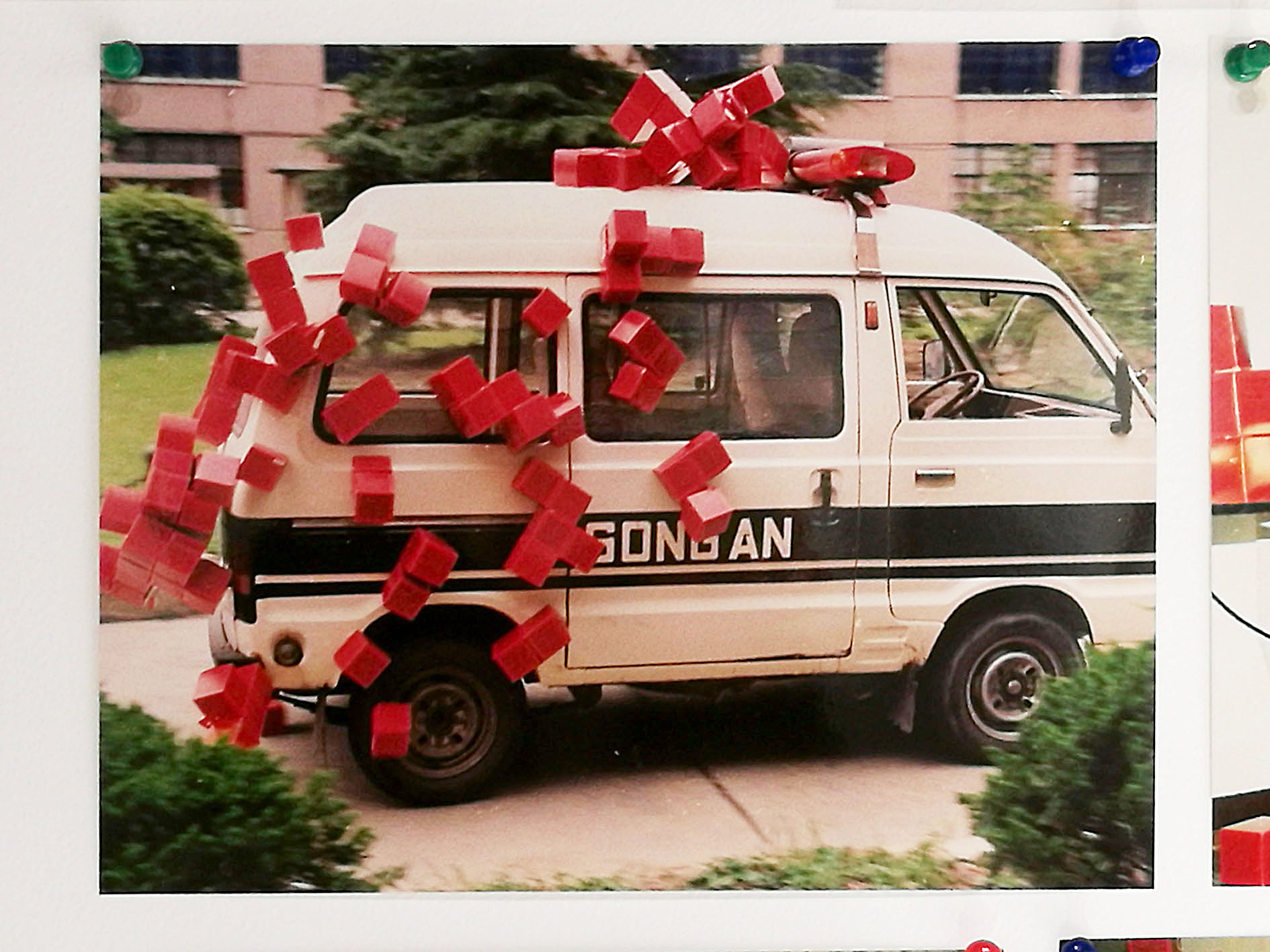

Another video offered a glimpse of Shanghai in 1990. Ni Weihua and Wang Nanming’s Continuously Spreading Event (1992) showed the distribution of red cardboard cubes to diverse urban locations, which were left out in the public for curious passers-by to interact with. In one scene, we watch as cubes are attached to a police van; then we see the driver, a policeman, waving at the camera before driving off. The scene is a world away from the monitored public spaces in Shanghai today. Now, legions of private security guards and several divisions of civil police, armed with whistles, hold vigil over incursions and unregulated activity.

The Chinese term for avant-garde—qianwei—is not a literal translation. The term implies the defense of new conditions. The exhibition constructed a history of the period where artists interpreted expressions of freedom in different ways. The freedom to accept foreign styles in both making and disseminating art, conflicted with the collective freedom associated with socialism and with national traditions. In 2018, when viewing this exhibition after another 25 years of precipitous change in China, the consequences of such tensions remains inconclusive.

“Avant-Garde Shanghai” is on view at Ming Yuan Art Museum, Shanghai, until March 25, 2018.