Shows

Asia’s Migratory Histories Explored in “Nomadic”

March 21–June 2

Nomadic

Jim Thompson Art Center

Bangkok

Historian Iris Chang proposed what she called “the power of one”: that “one person—actually, one idea—can start a war, or end one, or subvert an entire power structure.” Curated by Vennes Cheng, “Nomadic” at the Jim Thompson Art Center (JTAC) featured eight artists from Thailand, Singapore, Indonesia, Japan, Taiwan, and Hong Kong whose works form a constellation of Asia reimagined through stories of diaspora and human displacement. “This exhibition is about history but it is not a historical exhibition. History is about people moving,” said Cheng. “Nomadic” was a reminder of the many people whose power—and lives—are, far from Chang’s conception, consolidated within one piece of luggage, one sea-crossing, one train, one map, or one journey.

Across two gallery spaces and the building’s exterior, the exhibition facilitated meditations on the movement of the region’s people. The main gallery looks at Southeast Asia and its connection to Hong Kong. The centerpiece was Tintin Wulia’s (Re)Collection of Togetherness (2007– ), with the vibrant replica passports hanging mid-air like birds flocking together, with shared uncertainties of citizenship and communities for members of the Chinese-Indonesian diaspora.

The piercing sound coming from Law Yuk Mui’s video installation Song of the Exile: Rust Chipping (2022), recalls the process of hammering off encrusted parts of ships before new paint was applied. Law’s video centers around Damon Lee’s reenactment of a historical figure, an artist from Guangdong named Kwok Bing who became a career seaman and whose works recurrently appeared in the monthly staff magazine of the Royal Interocean Line. The retelling of Bing’s story in Song of the Exile and Law’s other archival-rooted projects about the Hong Kong-based ship company, afforded viewers a look into the semantic disintegration of fragile memories among populations adrift.

Placed directly opposite to Law’s works was Lin Yi-chi’s installation Transoceanic Practice (2021/24). Comprising a metal anchor standing on concrete floor and surrounded by the neon-lit words “Forever is (not) Eternity,” perishable in just a flicker of light. The anchor’s point of reference shifts according to one’s position, suggesting the many directions of travel taken by migrants.

Although many circumstances of movement posed in “Nomadic” were heavy, historical narratives, Cheng elaborated that struggles attached to moving may also be lighthearted—akin to the floating soft object as part of the collective Jiandyin (Pornpilai Meemalai and Jiradej Meemalai)’s On Adaptation (2009–24) series. Regardless of the location and weather, the soft object remains afloat, as new realities are invariably grappled with through the occasional, sometimes even humorous, lightness of transition.

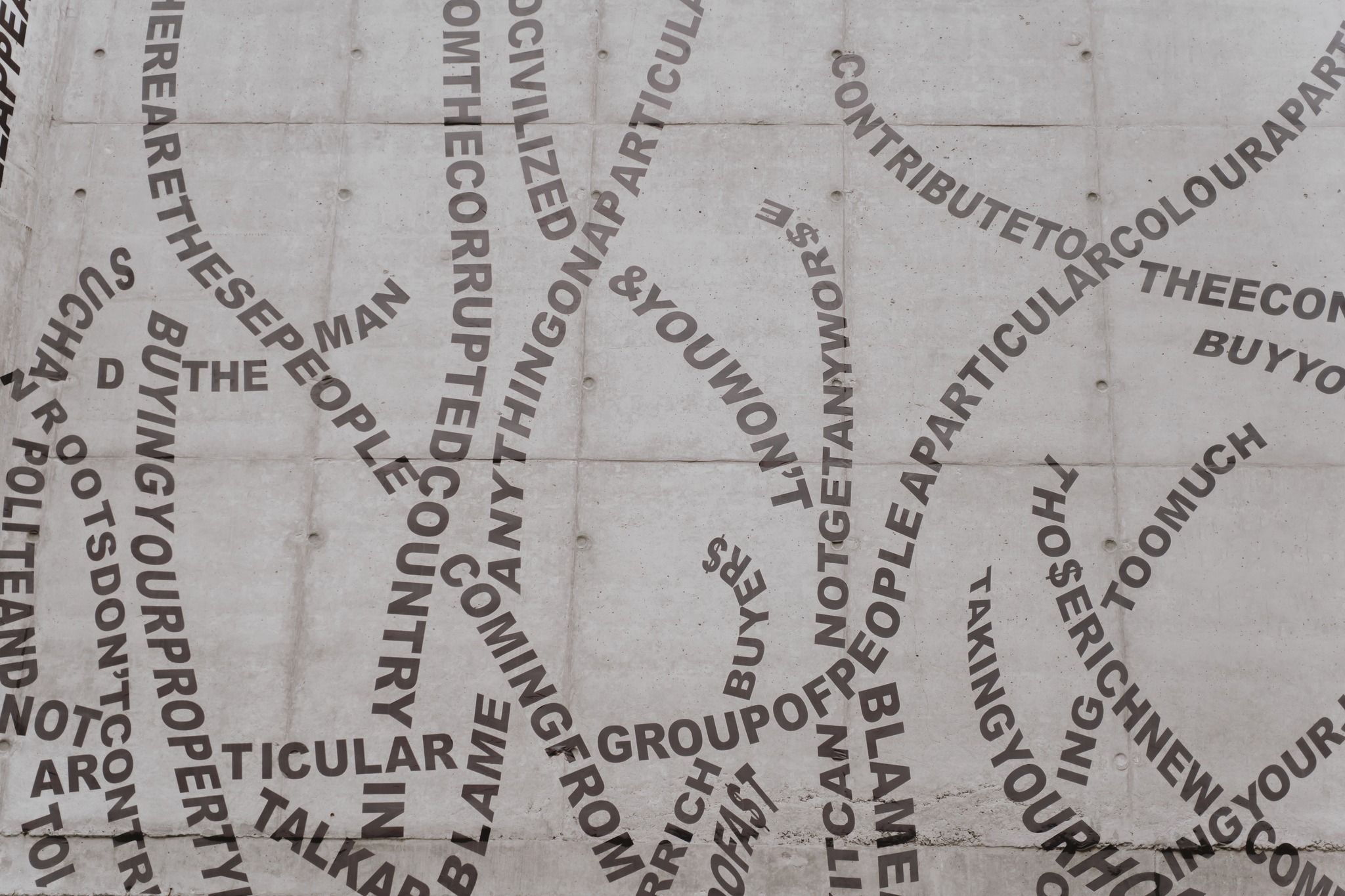

The marginal positioning of the soft object also posited the geographical fragility of minority ethnic communities. While On Adaptation is hopeful, persistent, and gentle, it rendered viewing Tsang Kin Wah’s Either / Or (2017/24) through the nearby glass panel more melancholic. Originally commissioned by the Vancouver Art Gallery in 2017, Tsang’s text installation was extracted from online forums where commentators discussed matters that often evoked racist sentiments, such as increased immigration of Hong Kong residents to Vancouver during the 1980s and 1990s in the lead-up to Hong Kong’s handover in 1997. The melancholia that stems from the crawling, parasitic misapprehensions, embedded the structure of the JTAC, suggested the literal institutionalization of these misapprehensions in many such institutional spaces.

The artworks that expanded the exhibition’s intergenerational retelling of identity were three prints from Sim Chi Yin’s The Suitcase is a Little Bit Rotten (2022), Climb, Crowd, Harbour, and a two-channel video, The Mountain that Hid (2022). The images of colonial archives from The Suitcase are interposed with those Sim’s intergenerational family. When the colonial gaze is juxtaposed with an intimate one, the archive is contested with competing historical narratives.

The second gallery focused on histories of East Asia. Tsao Liang-Pin’s Becoming Taiwanese: As Ritual (2018/24) is a reckoning of Japanese colonial Taiwan through images of people commemorating Chinese martyrs. The subversion of power dynamics in remembrance is palpably in conversation with Hikaru Fujii’s Mujō (The Heartless) (2019), a three-channel video of live performances by immigrants in Japan choreographed around archival footage at Civilian Training Centers—where Taiwanese people were trained as Japanese imperial subjects during the occupation era—with the archival footage and reenactment displayed side by side. Mujō is jarring as much as it is gnawing, discarding the formalities and prudence of current diasporic, colonial discourse, and, allowing confrontations with guilt, shame, and grief of historical wrongdoings to resurface. Mujō is a rude awakening of the suffocation imposed by systemic oppressors seeking to ossify the hegemony of a single national identity.

Reflecting on her exhibition in conjunction with ones at the Venice Biennale, Cheng remarked: “Conflict situations nowadays are more complicated; it used to be about whether you’re a foreigner or an alien, but nowadays you’ll probably be alienated in your own homeland.” With the Venice Biennale’s conceptualization of “Foreigners Everywhere,” and Frieze New York’s take on “Land Politics,” the art world is meditating on humanitarian crises, human displacement, mass movements, and relations beyond bloodlines. In “Nomadic,” generational estrangements, whether forcible or unwitting, were challenged by inert passports, archival research, and interposing into the colonial archive. Novelist Min Jin Lee’s multigenerational epic Pachinko (2017), which similarly delves into Japanese colonialism and migration, posited: “Living everyday in the presence of those who refuse to acknowledge your humanity takes great courage.” “Nomadic” was an amalgamation of the irrefutable presence of humans in transit between, across, and beyond borders and bloodlines.

Kamori Osthananda is a Bangkok-based art writer.