Shows

Anoli Perera’s “The City, Janus-Faced”

According to the Bible, the Tower of Babel is the reason for the world’s many languages. As the story goes, God decided to wreak havoc on humanity’s attempts at building a structure high enough to reach the heavens by introducing multiple tongues, estranging the tribes working collectively toward this goal. The allegory signifies a censure of humanity’s hubristic urban enterprises, but in a perverse way can also be taken as positive avowal of ethnic and linguistic differences. Babel thus also serves as an apt lens for examining Delhi-based Sri Lankan artist Anoli Perera’s solo exhibition “The City, Janus-Faced,” which commented on modern metropolises and the multiple, often-contradictory voices that are contained within.

The fabled ziggurat traverses across several myths and geo-temporalities—Mesopotamian, Judeo-Christian and the European Renaissance—to surface in the volatile present in Perera’s works, such as Dream 1, 2 and 3 (all 2017). The three paintings feature loose renditions of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s The Tower of Babel (c. 1563)—a fantastical cluster of windows and doors, which, in Perera’s work appear to act as buoys for anonymous figures. In Perera’s last panel, the tower seems to be bursting at the seams. Ruptures in the fabric of urbanity and the failures of modernity are further embodied in The Fall I and II (both 2017), as well as Spill 1, 2 and 3 (all 2017), which offer vignettes of humanity’s scamper for space, security and better living conditions. An installation titled Witness (2018), on the other hand, simultaneously evokes an experience of compression and distance by forcing viewers to engage with a CCTV feed of a robbery, narrated by the artist, via a peephole, in turns implicating the visitor in the inhabited reality and then estranging them from it.

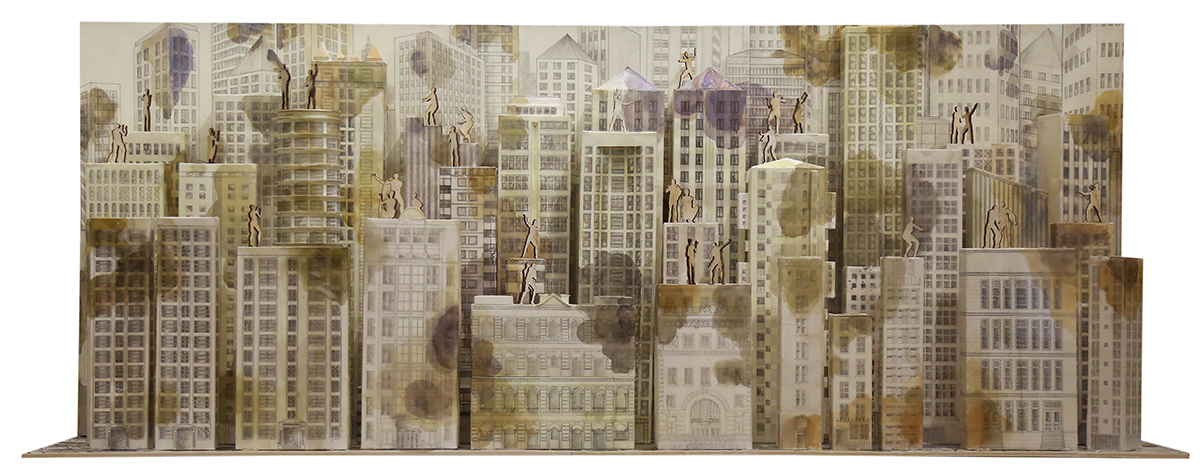

Other works in the exhibition took as their focus the annual October smokescreen that spreads its pall over the sprawling metropolis of Delhi—a phenomenon facilitated by laws established in the interest of multinational industrial giants. In the triptych Masked Series (2017), figures in gas masks are doubled over as shantytowns, rendered in an ominous grey, threaten to subsume them. The hyper-dense materiality of the city, including its amassed archaeology of refuse, is foregrounded in the sculptural works The City Series I (2018) and Elevated Utopias III (2017). With figures dangling in mid-air or dwarfed by skyscrapers, the surreal cityscapes bring to mind rapidly shifting cartographies and the vertical development of cities, often executed at the cost of rampant disenfranchisement and misery at the grassroots level. Both the flat and sculptural works paint the metropolis as a palimpsest of different and sometimes antagonistic visions of utopia, urban planning, economic and political interests.

The strange mixture of precarity and resilience that constitutes the matrix of the metropolis is indexed not only in the subject matter of the works but also in the artist’s sensitivity with regards to material. For instance, waxed and red-hued paper, commonly used for architectural modelling, is utilized in the sculptural installation The City Series III: Red Rain (2018). The work is reminiscent of a melting utopian dream, drenched in the uncanny “red rains” of Colombo, which, according to some locals, are the meteorological portents of the country's bloody political history. Similarly, the use of linked elastic bands composing the dark expanse of the installation The Shroud (2018) are evocative of both the clouds of war and the camouflage netting used in the army.

Shifting the focus to armed conflict was the last section of the exhibition. Perera attempts to situate the causality of some of the most major episodes of political discontent and human rights violations of our times—including the 30-year civil war in Sri Lanka between the Sinhalese majority and Tamil minority; the Karen conflict in Myanmar, hailed as the world’s “longest-running civil war”; and the Syrian Civil War that led to the ravaging of one of the world’s oldest cities, Aleppo—in the enclaving and structuring of their respective metropolises. The ambivalent nature of conflict is coded through the combination of warring elements such as cupids riding missiles and wrecking balls in The Play I and II (2017).

Finally, the show harkens back to the artist’s signature use of textiles as a medium. Forming the heart of the exhibition, The Long Walk (2018) comprises a cascading tapestry of rags. Embedded within sections of the fabrics were photographs documenting the pervasive tribe of the dispossessed, endlessly prospecting between cities, dreams and utopias.

Anoli Perera’s “The City, Janus-faced” is on view at Shrine Empire, New Delhi, until March 1, 2018.