Shows

An edict to forget: Vernon Ah Kee’s “Nothing important happened today”

“Nothing important happened today” is what King George III noted in his diary on the day that America declared its independence, at least according to the scriptwriters of The X-Files. For Vernon Ah Kee this apocryphal announcement stands in for the state’s long denial of violence, both in Australia and elsewhere, which he describes as its “edict of wilful forgetting.”

Ah Kee’s solo show was located within the old Spring Hill Reservoir, which sits adjacent to the windmill on Wickham Terrace, in Meanjin (Brisbane). What few of the city’s inhabitants know is that this was the site of Brisbane’s first public execution of two Aboriginal men, Mullan and Ningavil, who were hanged from the windmill in 1841. This grim history permeated the subterranean site of Ah Kee’s exhibition. The building was in effect the first of Ah Kee’s works in the exhibition, connecting the dots between the frontier wars and contemporary Australia.

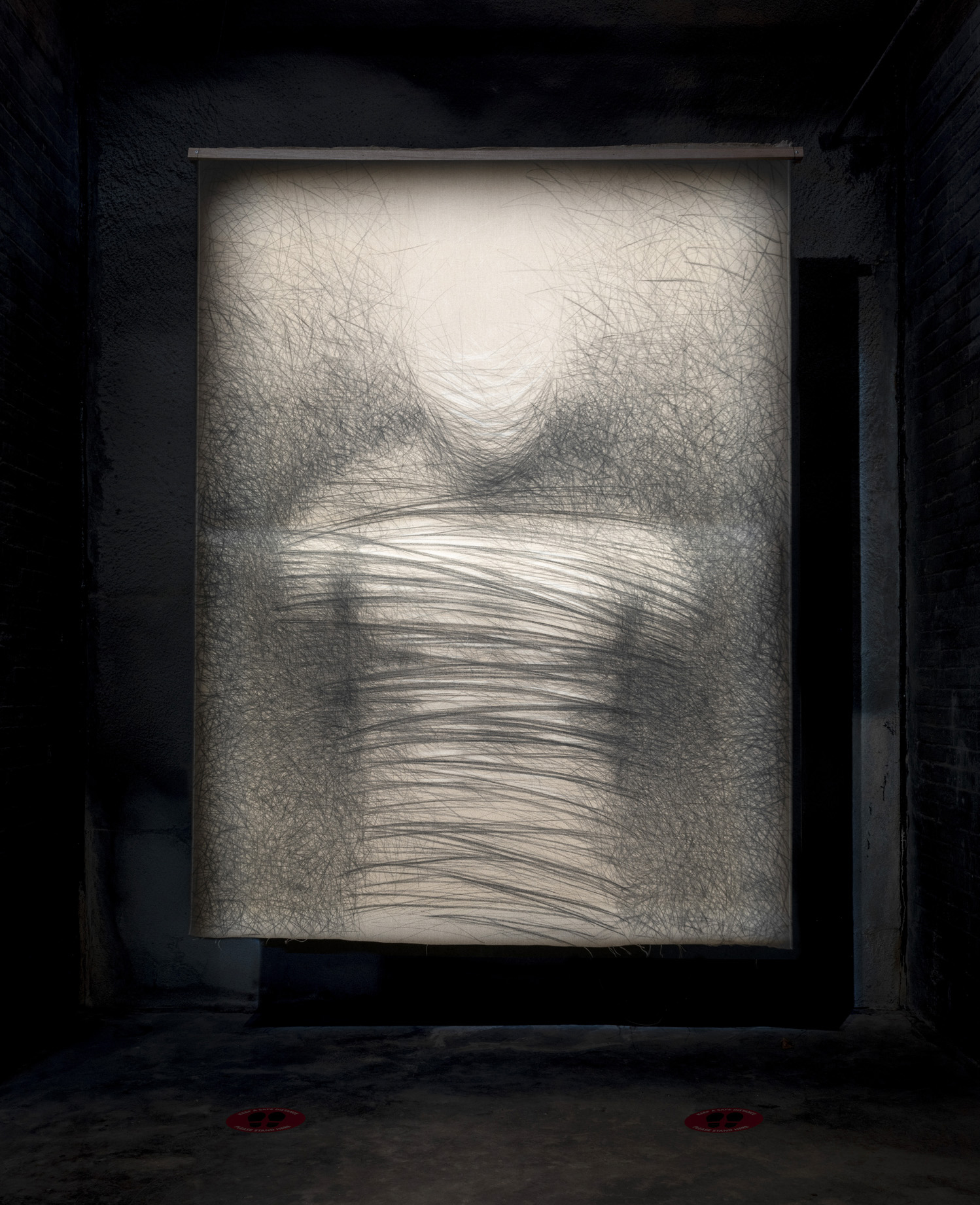

It’s worth saying that this was an extremely beautiful show: each work floated in the cavernous space, perfectly lit and glowing. Walking down into the reservoir, one first encountered two ghostly bodies seemingly constrained by the very charcoal lines that defined them. These massive drawings, lynching I and II (both 2015), were rendered in Ah Kee’s recognizable cross-hatching. Straight black lines mark the linen surface, with small sections of creamy-white hatched on each figure’s chest. These scores conjure traditional practices of scarification (as an initiation into adulthood) but equally the scars left by abuse. Ah Kee keeps these ambiguities in play: the Aboriginal person is initiated through scars both intentional and unwanted; they are perceived as featureless, ghostly, and unable to emerge fully in the national consciousness.

The charcoal hatching of the lynching drawings reappear on the surface of plastic police shields that hung from the ceiling in the reservoir’s central atrium. Here, the second subject of the artist’s critique became clear: police brutality. Scratch the Surface is the title given to this 2020 sculptural installation, while a three-channel video made in the year prior, which the artist projected among the arched nooks on the reservoir’s far wall, is named Kick the Dust (2019). The video shows three police shields dragged across a dusty road and then beaten against a rock, until they finally break into plastic shards. The grazing, wobbling, and cracking of the shields echoed throughout the underground space.

The works reference two examples of extreme violence committed against Black men in the United States and Australia: the 1998 murder of James Byrd Jr.—who was chained to the back of a pickup truck by three Texan White supremacists and dragged across a concrete road for five kilometres—and the killing of Kwementyaye Ryder in Alice Springs, who was kicked to death by five drunken White men in 2010. Although the court determined that Ryder’s death was racially motivated, the crime was categorized as manslaughter, for which the perpetrators received jail periods of between 12 months and four years.

The artist dragged and beat the police shields in an attempt to reverse the brutality and negligence of justice systems across the world. Yet, just as the charcoal hatching refers to two forms of scarring, the shield is a mutable metaphor in which the signifier points to both the tools of state oppression and the Black body that bears its brunt. Indeed, the plastic surface, once etched with charcoal or grazed by gravel, starts to look like wounded skin.

What does it mean, then, to endow a skin-like quality to the weapon that allows the police to inflict harm without even touching its victims? Ah Kee’s most important contribution is just this, as he re-inscribes tactility to a mode of violence that is so often sterilized through lagging bureaucratic systems and judicial loopholes. It would be a mistake to reduce the suggestive and complex materiality of these works to an assured punchline on the nature of racism. “Nothing important happened today” allowed for objects to take on multiple meanings, creating an affecting, yet not entirely obvious, tale of race, state, and memory.

Vernon Ah Kee’s “Nothing important happened today” was on view at Spring Hill Reservoir from September 22 to October 2, 2021.