Shows

Ala Younis’s “Plan for Feminist Greater Baghdad”

Simultaneously presented in London and Dubai, Ala Younis’s exhibition “Plan for Feminist Greater Baghdad” comprised a single, new installation. At London’s Delfina Foundation, the work, Plan (fem.) for Greater Baghdad (2018), was splayed across the gallery space. Stemming from Younis’s project for the 56th Venice Biennale, Plan for Greater Baghdad (2015), the piece constructs a multi-layered and overlapping timeline with multiple components that trace the planning, construction and activation of Baghdad’s gymnasium. The structure was designed by Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier during a shift in Iraq’s politics in the 1950s and was named from its inception as Saddam Hussein Gymnasium. Younis used this architectural project akin to a source text, treating the building as a site of analysis and interrogation to uncover overlooked aspects of Baghdad’s history and expressions of power.

Two digitally sculpted and 3D printed models formed the focal point of the installation. These renderings of the gymnasium are accompanied by a collection of characters frozen in various activities, signifying moments from Baghdad’s history. For example, one of the sculptures uses the building as a backdrop for the staging of six female figures, each one integral to the project and other Baghdad monuments, and yet who are under-acknowledged. Balkis Sharara is one of the represented protagonists, shown carrying a bundle of books and paperwork. This recounts the way she facilitated her husband Rifat Chadirji’s architectural practice, bringing documents to his cell while he was incarcerated in Abu Ghraib Prison during the 1970s for opposing then-president Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr’s demands to use his offices for the state’s secret intelligence services. Standing close by to Sharara is revered Iraqi-born architect Zaha Hadid and artist Nuha al-Radi, whose 1998 book Baghdad Diaries offers insights into life in Baghdad during the Gulf War. Each stands poised, almost defiant, with their backs to the building. Conceived through reading written accounts and oral histories, the installation brings to the fore the female influence on the city.

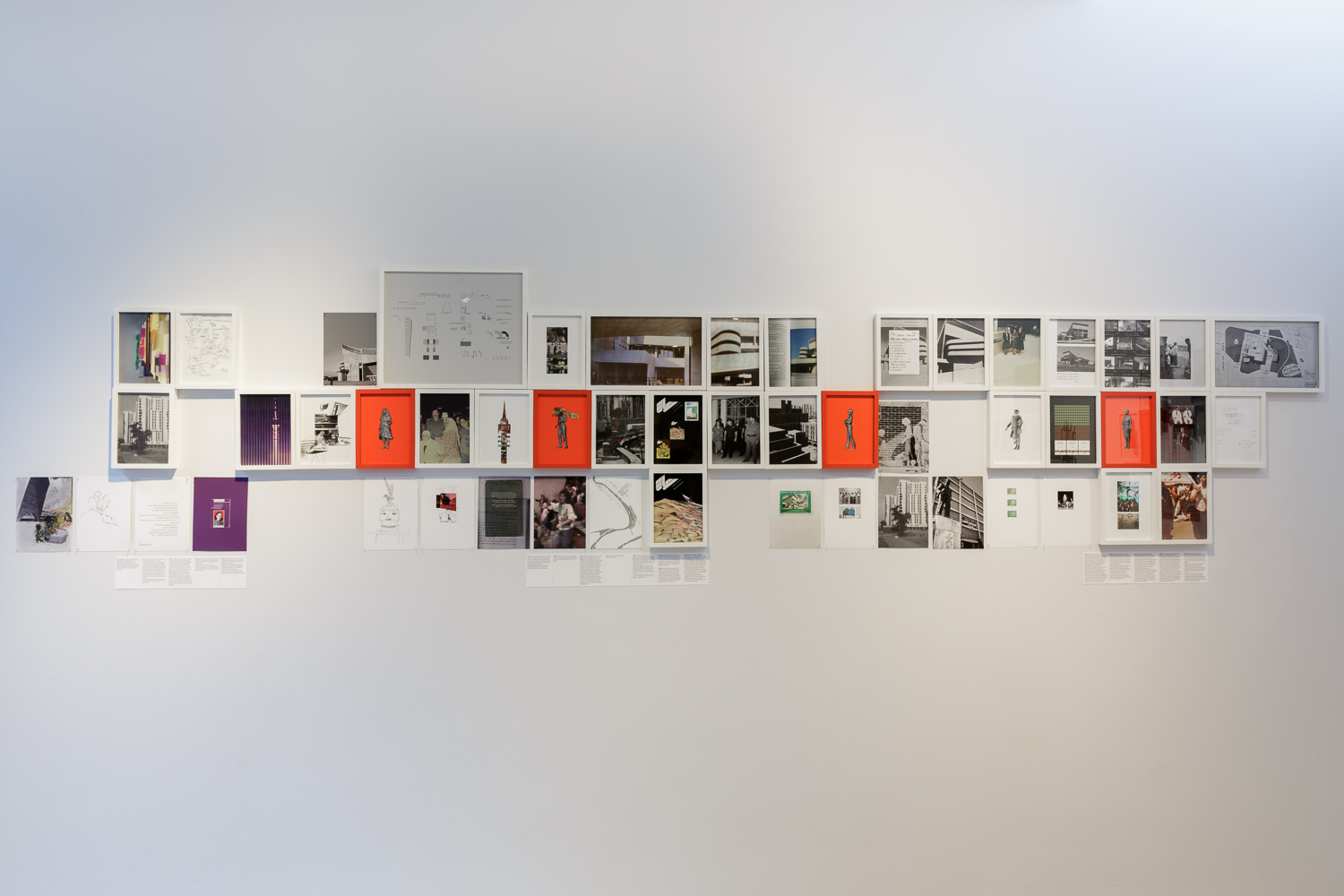

The surrounding timeline contextualized the model. An abundance of materials including archival photographs, architectural plans, postage stamps, digital images, letters and sketches were arranged in three rows, collating a range of narratives and situating the work in a wider political climate. The timeline references patriarchal rule, the country’s inauguration as a republic in 1958, as well as Saddam Hussein’s presidential take over in 1979 and subsequent modernization of the city. In one of the photographs, depicting students of Baghdad’s first female university, there were red flecks of paint, added by the artist to allude to a time when children were asked to dress in the colors of political parties: red or green, according to the influence of their schools. However, as Younis told me, this intervention in the material was not an attempt to offer an opinion or assessment, but rather “an attempt to merge and collapse several stories together, and [. . .] to understand, if possible, the history from its making.” Through both the archive and sculptures, Younis adds new dimensions to our understandings of the city’s multitude of characters and the waves of political changes that led Iraq from being fractional to consolidated via nationalization—all of which contributed to the city’s infrastructure and built environment.

Albeit subtle and latent, other seemingly fictional elements were woven into the work. A suited figure masked in a disproportionately bulbous Mickey Mouse head made appearances throughout the timeline, in addition to being rendered in one of the sculptures. This figure appeared imaginary but was actually pulled from the documentation of a new year performance inside the gymnasium in 1990. Younis stated that the importance of this lies not only in the events that unraveled later in that year, namely the Gulf War, but also that this event was the first footage she found of the gymnasium’s interior. It is this commitment to rigorous research, saturated with the possibility of an imaginary narrative, which makes the enigmatic work appealing. Offering a proliferation of documents and images, Younis makes demands on her audience and expects them to excavate their own storylines. As she told me, “There are the histories of Iraqi architects and artists in transit in other cities like Amman and London that I am currently exploring, among other issues related to the women architects”—the possibilities are infinite.

Ala Younis’s “Plan for Feminist Greater Baghdad” is on view at the Delfina Foundation, London, until March 24, 2018.