Shows

Adriano Pedrosa’s Bold Provocations in “Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere”

The modernist facade of the Central Pavilion, the primary venue of the International Art Exhibition at the Venice Biennale within the Giardini, is no longer all white. Instead, its front, including the columns and the architrave bearing the name “la Biennale,” has been painted over with colorful patterns and a lush landscape of streams, forests, fish, reptiles, and humans in ceremonial costumes. This transformation of the iconic building by the Indigenous collective MAHKU (Huni Kuin Artists Movement), from the Kaxinawá Indigenous Land of the Jordão River in the Brazilian state of Acre, was the first encounter with the many provocative curatorial gestures by Adriano Pedrosa for the 60th Venice Biennale, bilingually titled “Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere.”

Pedrosa challenges the canonical categories of contemporary art and art history itself, past and present—particularly in the framing of which peoples’ artistic productions are lauded, collected and preserved, and whose culture has remained “foreign” or outside of the recognition by institutional spaces for the visual arts. Yet, there is tension between actions taken in the name of visibility and the actual structures of representation—between short-term gestures and long-term change, respectively. Hence the boldness of Pedrosa’s proposition, and the many critiques and forms of resistance to it.

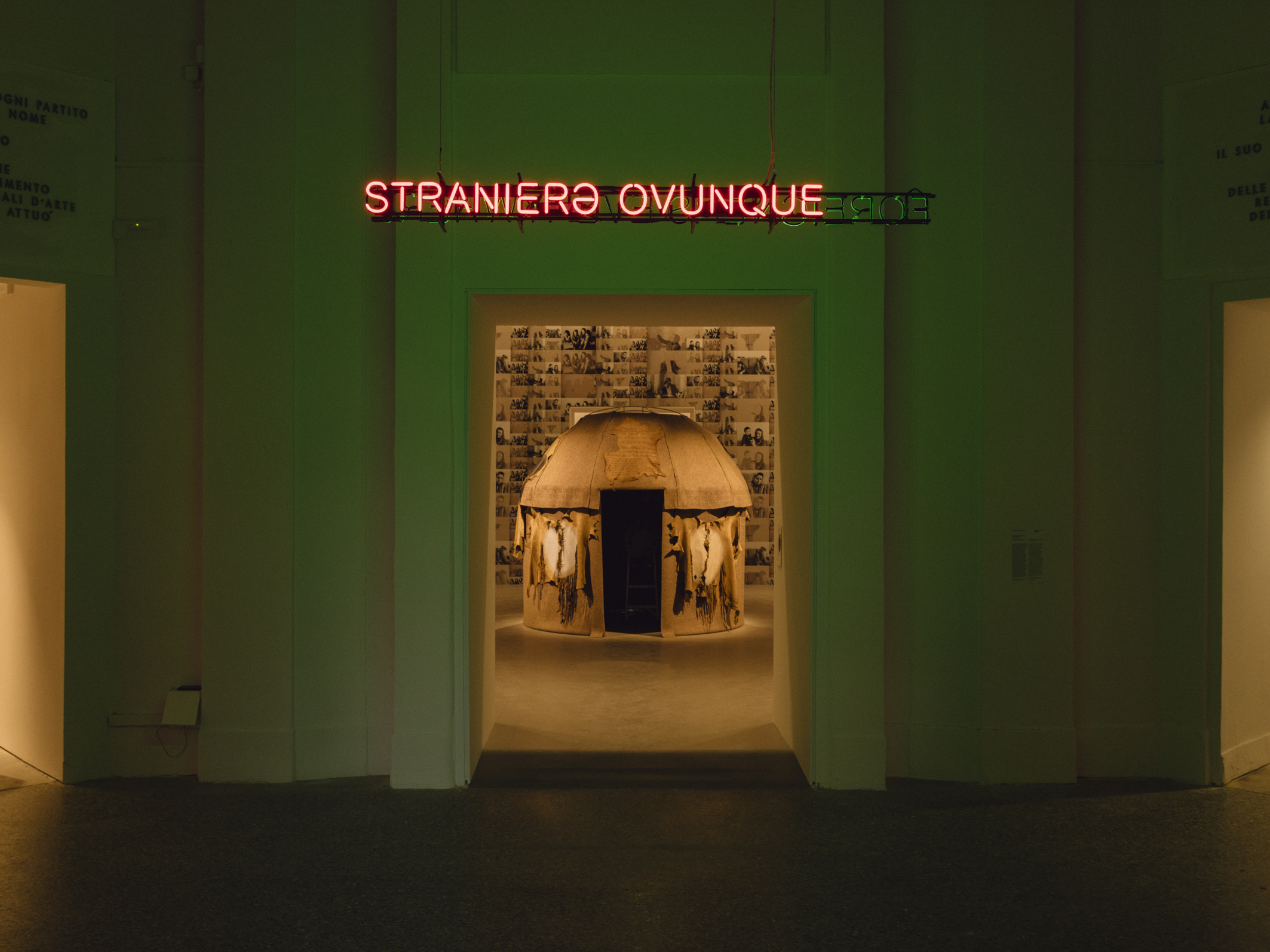

Inside the Central Pavilion in the Giardini, Pedrosa strongly laid out his thesis. The eponymous neon sign by the collective Claire Fontaine that inspired the Biennale’s title, reading “Straniere Ovunque” on one side in red and “Foreigners Everywhere” on the other in green, refers to a Turin anarchist collective that fought racism and xenophobia in the 2000s. Next, he staged a room-sized installation of works, including a nomadic yurt, Topak Ev (1973), by Turkish artist Nil Yalter, who moved to Paris in the 1960s and documented the many migrant workers who came to Europe from impoverished Anatolian towns of Turkey in that era as “guest workers.” The arrival of peoples from outside the continent is a recent history as well as an ancient story, though today it continues to animate rightwing discourses around the world—including in Italy.

Yalter’s room was followed by the first of Pedrosa’s three large thematic presentations of historical works—he calls them “Nucleo Storico” (“historical nucleus”)—this one devoted to abstraction. The first encompassed 37 artists from North Africa to West and South Asia and across Latin and South America, in an entire sweeping history of modernism told without figures from the United States and Europe. As a gallery of abstraction, we both feel the pull of familiarity, even while many of the specific names might be un- or under-recognized. Is this art history foreign to us, or are we foreign to it?

The paintings were displayed in an unconventional manner, stacked and clustered in pairs or trios, somewhere between salon style (floor to ceiling) and the modern style of hanging works all at eye level. One criticism of how Pedrosa has curated the “Nucleo Storico” is that he relied on thematic or stylistic similarities to bring together individual artworks by “heterogenous” (Pedrosa’s word) artists from multiple continents, aesthetic traditions, and artistic milieus. For instance, in the abstraction section, we see Japanese-Brazilian abstract painter Tomie Ohtake paired with Filipina modernist Nena Saguil. While it’s not immediately obvious what they share other than their square frame and rounded, hazy forms, it seems as if Pedrosa is posing a challenge to speculate on potential links. Another grouping linked the flat, solid shapes in Turkish artist Fahrelnissa Zeid’s canvas to those by Cuban abstractionist Carmen Herrera, Pakistani modernist Anwar Jalal Shemza, and Colombian painter Marco Ospina. Sometimes even the formalism did not quite align as with the pairing of the striped abstraction Water (1970) by Iraqi artist Mahmoud Sabri and the biomorphic abstraction by Lebanese artist Saloua Raouda Choucair Rhythmical Composition with White Sphinx (1951), which perhaps were connected through the artists’s origins in West Asia. We are left to imagine the possible histories.

Contemporary art historians working on non-Euro-American modernities have said that comparative modernities is no longer a new field—but for the art world’s most high-profile mega-exhibition, it still is. Yet it is also crucial to acknowledge that the Biennale relies on the research done by scholars, regional archives, and private organizations such as the Barjeel Foundation in Sharjah, as well as state-funded museums such as Mathaf in Doha and the National Gallery Singapore (NGS); these collections figure prominently in the “Nucleo Storico.” At the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP), where Pedrosa is the director, he has also shaken up the concept of history through exhibitions looking at the Afro-Atlantic population, women, Indigenous, and sexual diversity. It’s evident that Pedrosa understands both exhibition-making and collecting to be intertwined in the writing of history, whether a nation’s or the world’s.

The second “Nucleo Storico,” located in a pair of adjacent galleries, was devoted to portraiture, and featured 109 artists active in the 20th century in countries around the world. As with the abstraction presentation, many of the works are grouped into duos, trios, and other small configurations, with implicit formal connections such as self portraiture or depictions of lower-class laborers, while the historical biographical connections between the individual artists are unstated and likely nonexistent. For instance, self-portraits by Indonesian painter Affandi, Egyptian painter Ahmed Morsi, and Afro-Brazilian artist Yêdamaria hang together—their styles appear as disparate as their countries of origin—yet they are all evidently modernists grappling with their sense of self as artists. One evident aspect of the “Nucleo Storico: Portraits” is that most of the faces and bodies depicted in this section are non-white, again raising questions about whom can depict whom, while Pedrosa positions this “heterogeneous group” at the heart of the Biennale. On every wall label in the Biennale was a stated declaration of whether the artist has shown in past Biennales—another provocation by Pedrosa—with a large majority of them reading that this is their first time being shown in Venice, including a figure as iconic as Mexican artist Frida Kahlo.

There is another tension in “Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere,” a linguistic one embedded in the title. The question of foreignness—who or what registers as “foreign”—feels like a less fractious dialectic when the Latinate root of “straniero” (or the Portuguese estrangeiro, the French étranger, and the Spanish extranjero) is considered. As Pedrosa notes in his curatorial statement, “the stranger” is the unknown but also the unfamiliar and the uncanny—psychological states rather than bureaucratic, national ones—and is linguistically more fluid, as English words like “strange” and “queer” have become synonyms. To that end, Pedrosa foregrounds contemporary ideas of queerness while also moving beyond sexualities to present artworks by figures considered the outsider or self-taught, the folk artist, the Indigenous artist, as well as the disobedient ones who are often activists in the Disobedience Archive, a section of 39 artists’ videos from 1975 to the present compiled by Marco Scotini in the Arsenale around the two themes of “diaspora activism” and “gender disobedience.”

These are artistic identities already not entirely “foreign” to the Venice Biennale—many outsider and folk artists, for instance, were shown by Massimiliano Gioni in his excellent 2013 edition, while the powerful 2015 Biennale by the late Okwui Enwezor put Black, African, and activist artists at the core, and Cecilia Alemani vaulted many lesser-recognized female historical figures in her “Capsules” in 2022. Yet Pedrosa’s formulation is not to put them in league with Euro-American figures as a means of contextualizing or equating them, but rather to position them together, entirely outside those points of reference. Pedrosa boldly proposes in this arc-European context of the Venice Biennale: what might art and art history look like without its traditional narrative centers of power?

In the Giardini, beyond the “Nucleo Storico,” what Pedrosa does to is to position contemporary artists’ practice in dialogue with one another’s, across generations and geographies, such as in a room for queer abstraction with Evelyn Taocheng Wang’s washy renderings in watercolor of Agnes Martin’s blocky minimalist paintings and Maria Taniguchi’s black-brick grid paintings shown together with the tile-like ceramic abstractions by the late queer feminist Nedda Guidi. In another gallery of male artists, Filippo de Pisis’s still lifes and drawings of male sex workers from the 1920s and ’30s in Paris and Bhuphen Khakhar’s painting Fishermen in Goa (1985) were shown in a room with Louis Fratino’s canvases depicting scenes from 21st-century queer life, linking three openly gay artists from three countries and periods.

Kang Seung Lee’s contribution to the Biennale, Untitled (Constellation) (2023), is a work that itself connects the lives and works of queer artists, from photographer Tseng Kwong Chi to painter Martin Wong and choreographer Goh Choo San, as a memorial to lives lost, unseen, and perhaps almost forgotten. The figure of the refugee or migrant, as another form of foreignness, was referenced in a bold one-room pairing of Teresa Margolles’s bloody print of a human body, a young man who was killed on the border of Venezuela and Colombia, and Beirut-based Omar Mismar’s tiled mosaic of a floral-blanket, evoking the violent forms of disappearance among those migrating in search of better lives.

In the Arsenale, the second main site for of “Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere,” Pedrosa featured many artists working with textiles and artisanal craft traditions that have long remained outside the academy of fine art. This is not a novel curatorial exploration in itself (ceramics and textiles have become more recognized areas of practical and artistic study as well as historical research) but Pedrosa foregrounds artists working with and representing minority communities. In the Arsenale he offered grander-scale showcases of these practices, with less emphasis on pairing or grouping artists and therefore proposing a less assertive curatorial stance and fewer provocations compared to the historical parts of the exhibition.

Throughout the Arsenale section of the exhibition, Pedrosa points to how the use of artisanal techniques can be political, especially when they are collaborative and community-based. Near the entrance to the long L-shaped Corderie building, the Mataaho collective of Maori women created a woven mat (takapau, symbolizing birth) from industrial hi-vis tie-downs that covered the ceiling. From Argentina, Claudia Alarcón and the collective Silät produced richly colored and delicately amorphous abstractions from hand-spun, dyed, and knotted natural fibers. Fusing the textile practices with activism Güneş Terkol’s pair of fabric banners depicting protest marches are themselves designed to be carried in rallies. Reflecting the anguish of the ongoing war in Gaza, Dana Awartani’s installation of hanging fabric bolts Come, let me heal your wounds. Let me mend your broken bones (2024) was made by ripping and then repairing colorful fabrics, also done in collaboration with artisans.

There are also numerous biographical stories that reveal life on the margins of societies. Xiyadie’s large-scale paper cuts imagining gay love scenes in Chinese homes and gardens represent an engagement with the popular art form and life on the margins of society. A collector and synthesizer of world textile traditions, Pacita Abad was represented in Venice by three of her padded paintings (known as trapuntos) depict immigrants or migrant workers, including the nearly three-meter tall You Have to Blend In, Before You Stand Out (1995), which features a young brown-skinned figure wearing a Yankees cap whose brim juts out. A gallery dedicated to Bouchra Khalili’s works featured her seminal eight-channel installation The Mapping Journey Project (2008–11), which features interviews with migrants whose faces never appear on screen but only their hands as they diagram their convoluted and often treacherous passages to Europe.

Immediately following the stories compiled by Khalili was “Nucleo Storico: Italians Everywhere,” which features 39 artists of Italian descent who moved to other parts of the world due to economic hardship and famine (especially to South American countries such as Brazil, Argentina, and Chile). Here, Pedrosa employed postwar Brazilian architect Lina Bo Bardi’s iconic display structure of glass panels (known as “crystal easels”) slotted into in concrete cubes to showcase two-dimensional works (originally designed in 1968 for MASP), allowing access to the rear-side of the canvas and frame and changing our relationship to “two-dimensional” artworks. Among these myriad stories, Pedrosa provocatively demonstrates that like many migrants arriving in Europe today, Italians were, only a couple of generations ago, the foreigners that were everywhere, and that they brought their culture and skills with them, continuing to shape the art communities around the world.

The forms of violence that foreigners are subjected to—or the forms of violence that are used to make us feel foreign—were dynamics explored in several impactful live performances. The 30-minute performance of Isaac Chong Wai’s Falling Reversely (2021–24) with nine dancers (including the artist) is based on attacks against Asian migrants and queer communities in Europe and elsewhere, with performers falling to the floor and alternately supporting one another. (Chong’s performance also plays on large screens in the space throughout the Biennale.) Ahmed Umar’s video installation and live performance of a Sudanese bridal dance, Talitin, The Third (2023), enacts rituals of Sudanese women’s culture that he was not allowed proximity to after he hit puberty (and, which, due to more conservative religious constraints, is not possible to practice in any longer). Now based in Norway, he has reclaimed this interest and desire through performance, as well as proposing a queer identity to inherit the cultural form. Filipino choreographer-dancer Joshua Serafin presented both the installation and the live version of Void (2022– ) featuring the artist crawling on sand and covering his body in a black-dyed lubricant that is pooled in a large hole on stage, in a powerfully ritualistic performance that explored the animist creation myths and nonbinary identities in the Philippines that were suppressed by Catholicism during the Spanish colonial era. These performative works brought the contemporary body—as a subject of repression and violence, and resilience and care—to an exhibition otherwise overflowing with material culture.

Pedrosa’s provocations in the Biennale are evidently political, in the context of devastating wars with colonialist and genocidal ambitions, right-wing religious fundamentalism dominating more countries’ politics, climate change and environmental degradation contributing to more than 100 million refugees worldwide, and rising class/income disparities. The elite cultural world represented by an institution like the Venice Biennale—in which nation-states, museums, multinational art galleries, and global patrons compete to be seen—is interconnected to these economies, politics, and histories. Here, Pedrosa has staked a claim to do in the Biennale what large-scale collecting institutions still have not achieved in telling a global art history that takes a fuller scope of 20th-century life into account. Pedrosa’s challenge to his imagined audience, in bringing so many names and faces of color, queerness, indigeneity, and marginality all together, was ambitious and, ultimately, if it came off as provocative, then it was a success.

HG Masters is deputy editor and deputy publisher at ArtAsiaPacific.