Shows

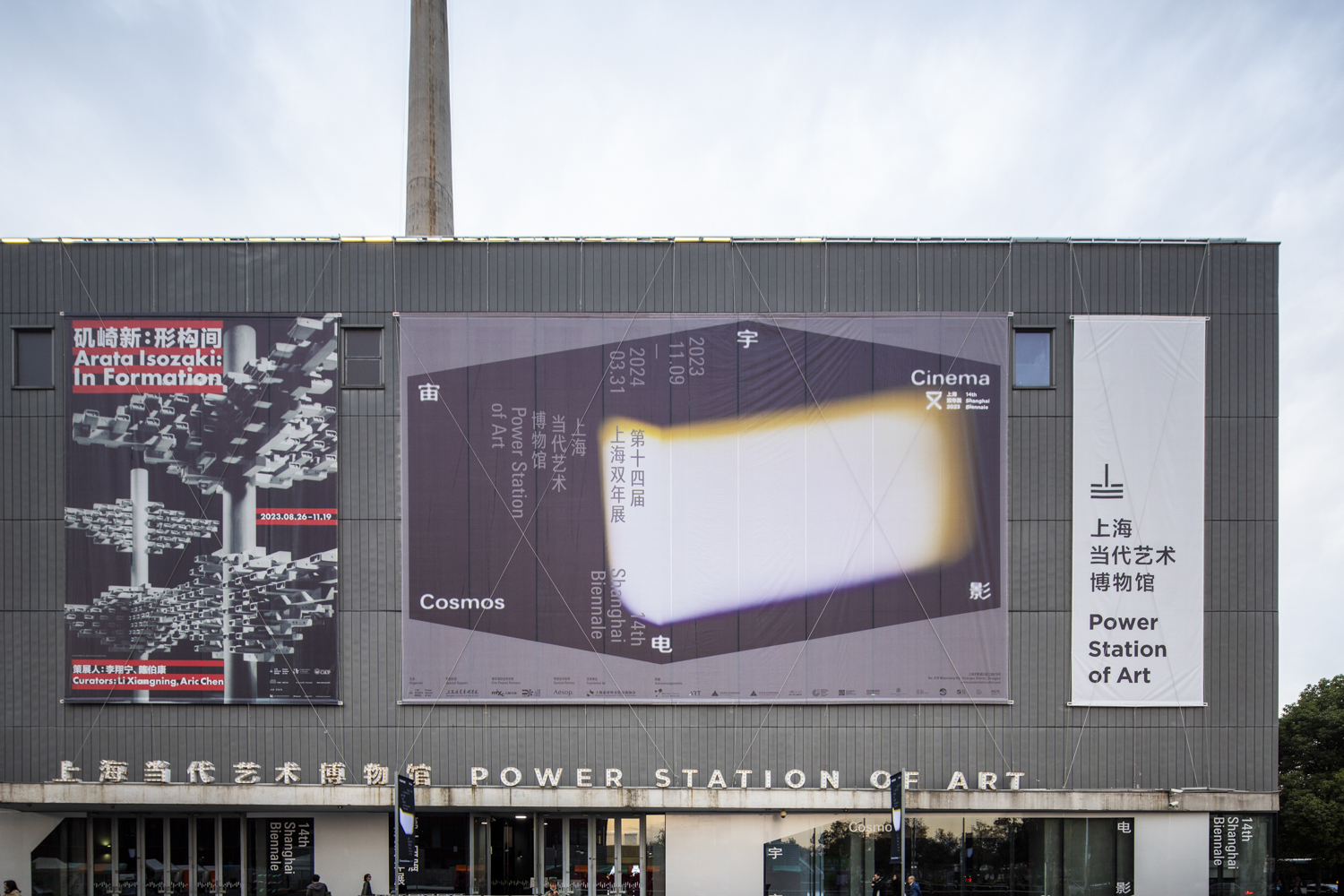

14th Shanghai Biennale: “Cosmos Cinema”

Despite how strongly we now associate the concept of “cosmos” with science, thinking about the universe still evokes a sense of nostalgia. Recalling memories from adolescence—a field trip to the planetarium, looking through a telescope in the wilderness, a science lesson at school—our fascination with outer space seems inherently romantic. This sentimentality is reinforced by countless science-fiction films, from Georges Méliès’s early adventure-fantasy Le Voyage dans la Lune (1902) to recent space thrillers, such as Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar (2014) and Denis Villeneuve’s Arrival (2016). Cinematic language has allowed the realization of human fantasy to venture into unknown territories, laying the foundation for “Cosmos Cinema,” the theme of the 14th edition of the Shanghai Biennale, which took place at the Power Station of Art and headed by chief curator Anton Vidokle, of e-flux, and a curatorial team which included Xiang Zairong, Hallie Ayres, Lukas Brasiskis, and Ben Eastham.

The curatorial framework for “Cosmos Cinema” was inspired by Vidokle’s long-held interest in Russian cosmism, a philosophical and cultural movement centered around immortality, resurrection, and space travel during the Russian Revolution at the turn of the 20th century. Vidokle’s interest in Eastern European and Asian philosophy is by no means accidental, as these frameworks strongly contrast with contemporary Western cosmologies that seek to rationalize planetary colonization, resource extraction, and other survivalist efforts. Russian cosmism facilitates an alternative relationship between humans and the universe, including through philosophy, art, mythology, and spirituality. Accordingly, “Cosmos Cinema” is divided into nine sections, further referencing the ancient Chinese cosmology of Nine Heavens: “Freedom of Interplanetary Movement,” “Partial Eclipse,” “Ten Thousand Things,” “Solar Assembly Line,” “Cinema Cosmos,” “Futurisms,” “Reflexology at a Distance,” “Of Time and Space,” and finally “Brave Wind and Rain.”

.jpg)

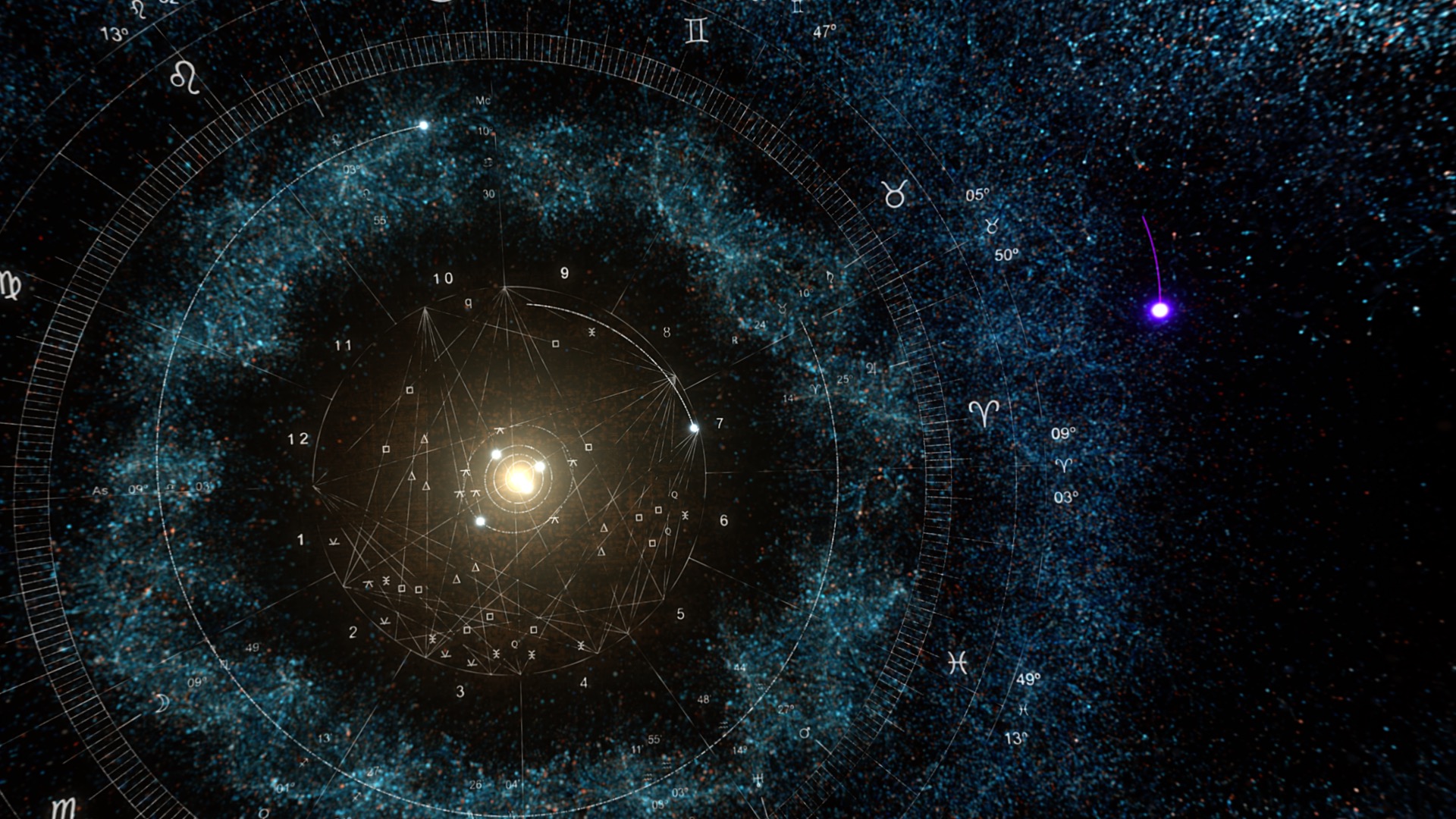

Kicking off the cosmic experience, Trevor Paglen’s large-scale installation Prototype for a Nonfunctional Satellite (Design 4; Build 4) (2015–18) and his two Orbital Reflector series (both 2015–18) assert a clinical, metallic impression of a space mission, which was in fact the prototypes’ original purpose—to launch “purely artistic” objects into orbit and render human artistic expression within the extraterrestrial arena. While Paglen’s “artistic object” was lost in space due to the United States government shutting down communications with the rocket carrying the “satellite,” esoteric practices like astrology and the association between the cosmos and human sentiments have fulfilled our artistic imagination of the sky long before Paglen’s “artistic object” came into orbit. For thousands of years, societies have observed the night sky and tracked the movements of stars, seeking to determine individual and collective fate.

In “Partial Eclipse,” Taiwan-based artist Yin-Ju Chen’s newly commissioned 16-minute video essay Somewhere Beyond Right and Wrong, There Is A Garden. I Will Meet You There (2023) laments her mother’s passing by examining the Chiron star, which signifies nurture and healing in Greek astrology. This astro-relationship could be heard from the Armenian-Lithuanian artist and composer Andrius Arutiunian’s sound sculpture You Do Not Remember Yourself (2022), a one-by-six-meter brass instrument that perpetually oscillates resonant sounds. The work represents Kepler’s concept of harmonia mundi, the “world’s harmony,” which sought to mathematically prove the Pythagorean theory of musica universalis. Both concepts attempted to establish that stars produce sounds that are audible to the human soul.

One aspiration of “Cosmos Cinema” was the Biennale’s attempt to diversify global perspectives, as if seeing the world through a kaleidoscope. In the section “Ten Thousand Things,” Uzbekistani artist Furqat Palvan-Zade transformed his research on medieval and early-modern Islamic astronomy into a lightbox installation, The Moon (2023), displaying 12 lunar craters bearing the names of its corresponding, medieval polymaths and poets by the International Astronomical Union. Meanwhile, Filipino artist Kidlat Tahimik’s installation of tapestries and wood carvings Cinema tonto, cinema indio (2021–22) presents a reimagination of Indigenous movie theaters, where Aboriginal stories are conceived in a world without colonialism. Singapore-based artist Ho Rui An’s documentary Lining (2021) relays the history of Hong Kong’s textile industry through its traces of material networks, which connected the city to mainland China before the establishment of the People’s Republic. Through different interpretations of cultures and contexts, “Ten Thousand Things” revealed a decentralized worldview often dismissed by the epistemes of a neoliberal epoch.

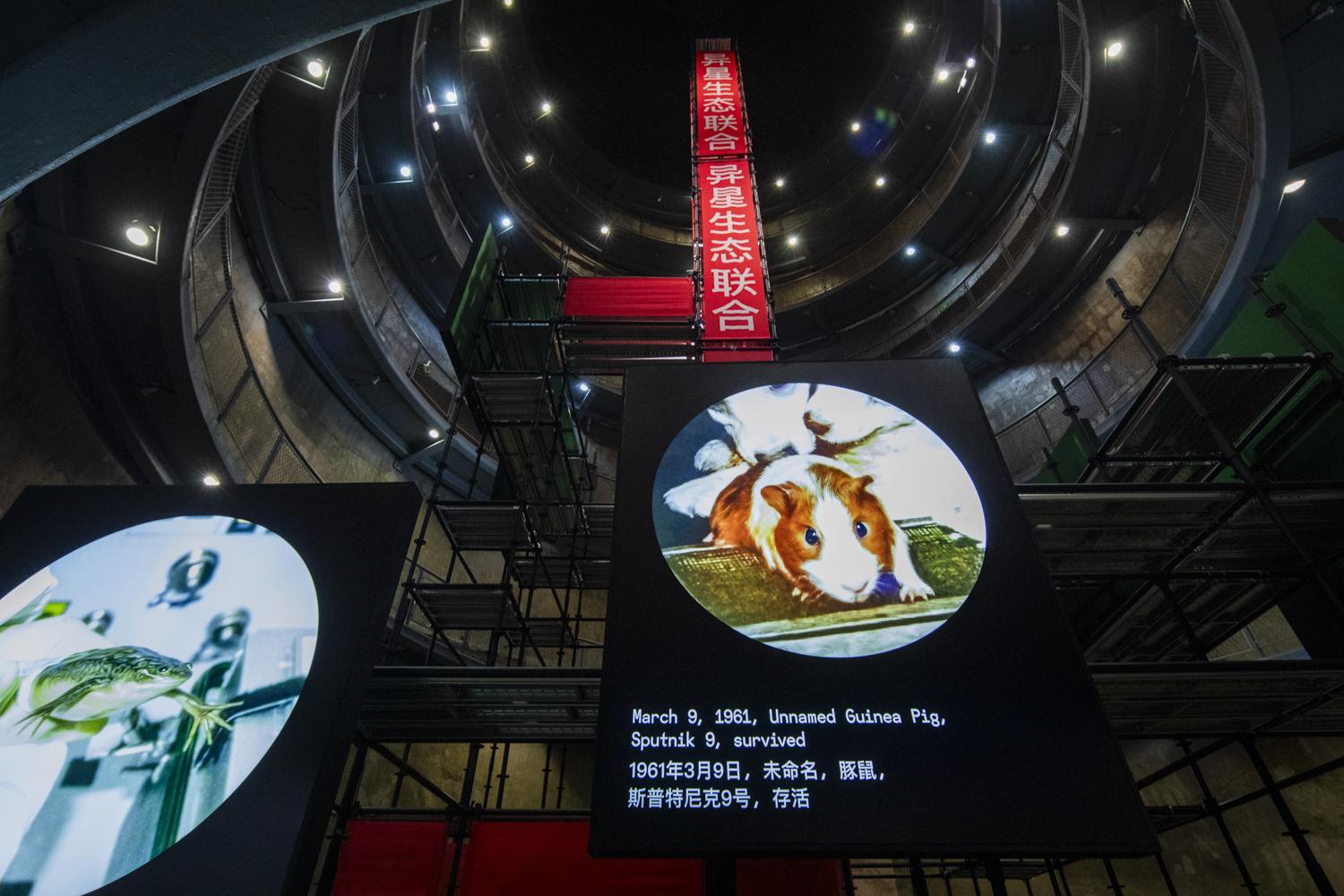

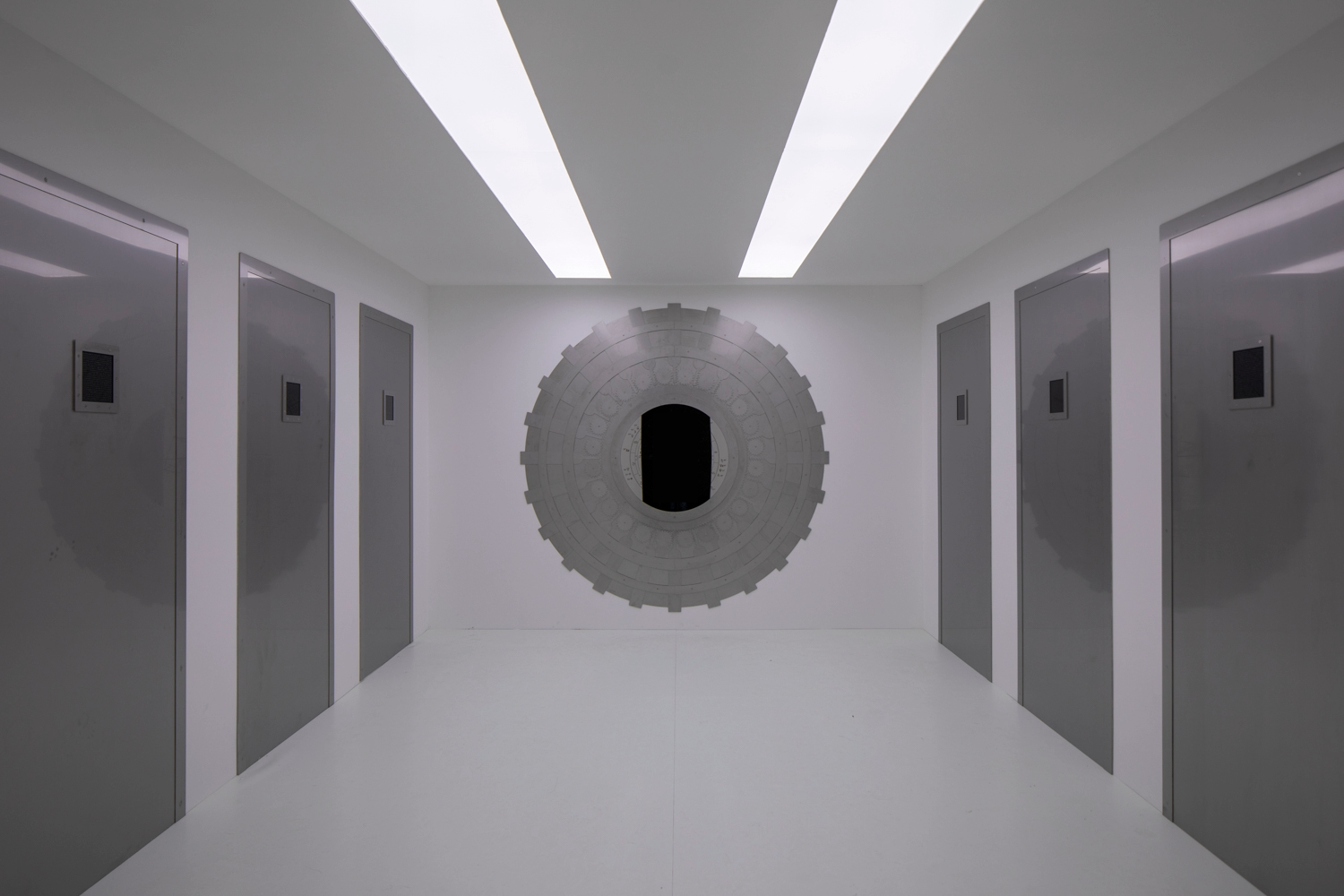

A certain sentimentality permeated the exhibition, with the dim floor light guiding visitors through the Power Station as a reminder of the cinema experience. The movie-theater-like environment was only interrupted once you walked into the cavernous chimney-like space, where the second-largest installation of the Biennale stood. Titled Exo-Ecologies (2023), Dutch artist Jonas Staal’s work comprises a scaffolding presentation of billboards depicting different profiles on animals that were sent to space in recent human-astronomy history. The launch-site-looking installation commemorates the numerous nonhuman lifeforms that have paved the way to outer space.

At the core of “Cosmos Cinema” is the section “Cinema Cosmos,” a reversal of the theme that revealed the true intent of the Biennale: while what we see in the sky has already passed (light travels for billions of years before it reaches us), we too are beams of light and waves of sound, dispersing our traces into the universe. This central section showcased Carsten Nicolai (Alva Noto)’s COSMOS (2023), a nearly-two-hour mix of 14 tracks composed for the exhibition, with several using samples of electromagnetic signals from outer space. If physical artworks occupy the spatial dimension, Nicolai’s COSMOS extends its occupation into the realm of time with sound dispersing like an echo of our cosmic signal. Nearby, the “Futurisms” section, including the Costakis Collection of early-modernist Russian paintings, reinforces the Biennale’s goal of re-establishing connections between Russian avant-garde and cosmism. But from the Russian Revolution to post-Covid socialism, the divergence of communism’s modern development in Asia poses a haunting juxtaposition in ideology.

At the same time, the apparent party-state capitalism that dominates contemporary China’s social structure has evolved into its own version of futurism. This worldview can be seen in the Guiyang-born artist He Zike’s video work Random Access (2023) within the same section, a Wong Kar-Wai-esque journey of a taxi driver and her customer (played by the artist’s parent) dreaming of the cloud memory stored at the largest data center and its transmission through the largest telescope in China, both located in artist’s hometown. Lucid yet depressing, her film reminds us that we have become dependent on capitalism’s control of data sets to store and recall our memories.

Approaching the end of the Biennale, spirituality and human bonding returned to conclude the journey of “Cosmos Cinema.” In his What is your |x| series (2020) from the “Reflexology at a Distance” section, the Berlin-based Vietnamese artist Sung Tieu presents eight steel doors with imprints of horoscopic descriptions as well as a trompe-l’oeil steel sheet with an inscription of the artist’s birth chart. Sung questions whether descriptions of one’s character are inherent, or learned to form our psyche. And in “Brave Wind and Rain,” the Palestinian-English artist Rosalind Nashashibi’s I Ching-structured 67-minute film Denim Sky (2022) brings a fictional story that casts her friends and family as cosmonauts to seek a new form of spacetime travel through bonding.

The cosmos is fascinating because the vastness of the universe triggers us to question life’s meaning. In the words of Nietzsche, “If you gaze for long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you.” The sheer emptiness of this void forces us to look inward, returning our spiritual and social connections. The aforementioned works return to an anthropocentric framework despite breaking away from solely being observers of the cosmos; they each attempt to establish an alternative relationship between us and what is “out there” that is too often obscured by our desire for material extraction and dominance. “Cosmos Cinema” was a timely exhibition on the discrepancy between people and power structures, particularly under our current geopolitical conditions.

Alex Yiu is associate editor at ArtAsiaPacific.