People

Xiyao Wang: Boundless Like the Wind

Spring conjures up a sense of renewal. It is a time where the greenery emerges from its cold slumber and flowers bloom in vibrant colors. It is where possibilities seem endless, boundless even. The Berlin-based artist Xiyao Wang shares these sentiments as well, tapping into what it means to be physically liberated through paintings that evoke visual impressions of movement across the canvas. Through twists and turns, leaps and twirls, Wang’s mark-making embodies a vastness that one can almost imagine extending outside of the confines of the physical canvas. ArtAsiaPacific’s Camilla Alvarez-Chow reached out to Wang to ask more about the artist’s practice, her current show at Massimodecarlo gallery in Milan, titled “The Blue Hour,” and how she achieves that sense of boundlessness in her paintings.

Your academic training has been quite extensive, with bachelor’s degrees from the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute and the University of Fine Arts of Hamburg. How did the two experiences compare? And how did those experiences shape your practice today?

Both art academies had a great influence in the beginning of my artistic journey, but the ways in which the Chinese and the German universities have influenced me are very different. In essence, the German approach prioritizes creativity, whereas the Chinese one emphasizes more on artistic techniques. I derived significant benefits from both art academies, and my practice matured through a synthesis of the best elements from each system. I have gained a profound understanding of discipline and technical skills from my time in China and a keen appreciation for ingenuity from my experience in Germany.

However, naturally, each methodology has respective disadvantages as well. In Germany, for instance, one’s need to plan independently for your studies and studio schedules can result in significant time loss if you have no discipline. Whereas in China, you have a schedule from morning to evening that is given to you by the academy. I am glad that I only moved to Germany at the age of 22, as I might have been overwhelmed if the same self-responsibility was required from me at the age of 18. During my undergraduate studies in China, I acquired a lot of knowledge about Western and Asian art history, as well as developed a clear objective upon my arrival to Germany. I also studied for half a year in New York, at the State University of New York at Purchase (SUNY Purchase)—that was a completely different experience, and I also learned a lot there.

You have shared in previous interviews that you have a daily routine as part of your studio practice including reading, a tea ceremony, and playing the guqin, after which you would begin to paint in the late afternoon or evening. Now that summer has arrived, is your studio routine any different? How about during the rest of the seasons (autumn and winter)?

This summer I am very busy and traveling a lot. In June I attended Art Basel in Switzerland, where my paintings were on display. Afterwards I went to Milan for my solo exhibition at Massimodecarlo, and then visited the Venice Biennale. In October I will go to Thailand for the Bangkok Art Biennale and my solo exhibition at Tang Contemporary Art.

When I am in my studio my routine is always the same, it doesn’t matter which season, as this has become a fundamental part of my creation. When possible, I also like to swim in lakes, or even better, the sea. Drifting in deep water makes me feel free. For example, this summer I swam in the Mediterranean Sea, which has inspired my new series.

Interior view of XIYAO WANG’s studio. Courtesy the artist and Perrotin.

Your gestural mark-making puts an emphasis on communicating movement. How did this become the focus of your artistic expression?

Even when I was an art student in China, I sometimes painted while dancing to experimental electronic music and death metal. Physical exercise serves as a significant source of inspiration and I have engaged in a multitude of athletic pursuits, including traditional Chinese dance, followed by ballet and kung fu. Through all this different training, I have discovered different states of strength and physicality. I learned to engage my mind through different body movements, which I can then translate into my artistic creations. The act of painting provides the most complete sensation of weightlessness and boundlessness where it is exemplified in the lines of my artworks.

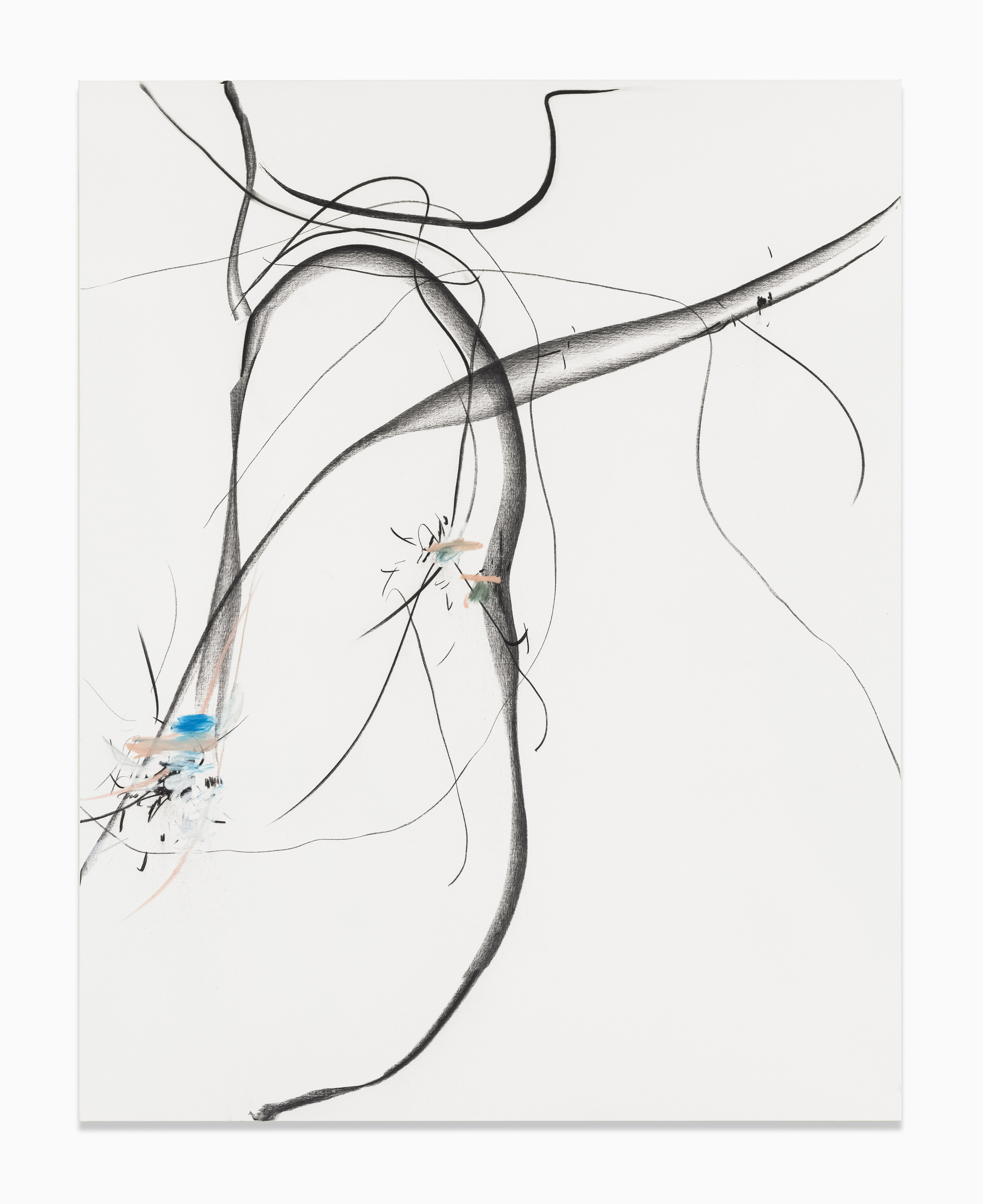

When it comes to the elements found in my paintings, I often experiment with different materials for drawing lines, exploring the expressive potential of different textures. Simultaneously, I strive to maximize the freedom of lines, using the same material (such as the black charcoal sticks that I am using a lot currently) to allow lines to traverse space and dance on the canvas through different speeds, rhythms, weights, thicknesses, and turns, breaking and transcending it with precision yet without tension, airborne but not frivolous.

XIYAO WANG, The Blue Hour No. 1, 2024, oil stick, charcoal on canvas, 200 × 190 cm. Photo by Roman Marz. Courtesy the artist and Massimodecarlo, Milan.

XIYAO WANG, The Blue Hour No. 2, 2024, oil stick, charcoal on canvas, 190 × 150 cm. Photo by Roman Marz. Courtesy the artist and Massimodecarlo, Milan.

Your current showcase at Massimodecarlo in Milan, “The Blue Hour,” presents paintings centering on the theme of spring and capturing the titular blue hour—the time when day transitions to dusk. How did this season, and this moment of the day in particular, motivate you to create this series?

I was born in the spring. The season of spring is characterized by renewal and rebirth, with the emergence of fresh green and flowers in abundance. It is the season of growth and life.

Even during the years of the pandemic, I was still visiting my studio at the academy in Hamburg as it was only a ten-minute walk away. The springtime scenery on my daily walk through the park by the water inspired me tremendously.

Indeed, the majority of the paintings I am showing in Milan were inspired by Berlin’s previous spring season, particularly by the phenomenon of the blue hour in the evening. That was also the time when I would begin to paint this series of works. Actually my last exhibition has two titles, one in English “The Blue Hour” and another in Chinese 阳春召我以烟景 (“The warm spring beckons me with its hazy scenery”). The latter is derived from a poem by Li Bai (701–762 CE)—one of my favorite poets from the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE)—in which he celebrates and lives in the fleeting moment.

Installation view of XIYAO WANG’s Echappe No. 3, 2024, oil stick, charcoal on canvas, 200 × 190 cm in "The Blue Hour" at Massimodecarlo, Milan, 2024. Photo by Roberto Marossi. Courtesy the artist and Massimodecarlo.

When it comes to your attempt to create a sense of boundless freedom in your work, how do you overcome the physical and material limitations of the canvas?

Actually what I am looking for is not only physical but also psychological. The tangible experiences of “boundlessness,” like drifting in the sea with its endless perspective, always helps me find clarity in what it means to be boundless. The canvas can never limit me and my lines, because the movement of the lines continues outside of the canvas and keeps on growing. Just because the border of a canvas stops my arm, it doesn’t mean the energy stops there.

How do you see contemporary technology and media influencing your paintings?

Of course, to live in our time also means that contemporary technology and media are unavoidable. But as I suggested earlier, my art is mainly influenced by the nondigital world, both past and present. Most inspirations that fuel my creative process emerge from the lived experiences of my immediate surroundings, sometimes from the distant past or mythology. Painting itself has a long historical tradition, it is definitely not something new. I, however, still chose it as my main medium because I like the sensation of touching the canvas with my brush, and that I can do it on my own with my hands.

What about the distant past inspires your work?

My artistic output draws inspiration from a multitude of sources, including historical and mythological roots. Li Bai, who is the most celebrated poet in Chinese culture, sometimes serves as a source of inspiration. For my show at König Galerie, “On the Way to Penglai Island” in 2023, where the legendary Chinese island sanctuary from Chinese mythology, Penglai, was my primary source of interest and inspiration.

I also really appreciate the text 林泉高致集 (Lofty Record of Forests and Streams) by Guo Xi from the northern Song Dynasty in the 11th century. Guo talks about his studio life and practices. I attempted to emulate his approach by taking the time to listen to my inner self and find a sense of profound tranquility.

My inspiration is not limited to Chinese culture. For example, I have traveled to the Mediterranean as I am also interested in the classical mythology of ancient Greece.

XIYAO WANG, Zhuangzi Dreaming of Becoming a Butterfly No. 3, 2023, oil stick, charcoal on canvas, 250 × 450 cm. Photo by Roman Marz. Courtesy the artist and Massimodecarlo, Milan.

Looking ahead, you will participate in the upcoming Bangkok Art Biennale this October. Do you have an idea of what artworks you will be showcasing and how your works will resonate with the theme of “Nurture Gaia”?

“Nurture Gaia” will be my first time exhibiting in Thailand, and at the same time I will have a solo exhibition with the Chinese gallery Tang Contemporary Art in Bangkok. I will also be there for the opening and will do an artist talk on the 26th of October during the opening week of the Biennale.

Some of the paintings that I will showcase at the Biennale are large in scale. One of them being Liang Xiao Yin No. 1 (2023) which is around seven meters wide and three meters high, and another titled Before the Sun Goes Down No. 1 (2024) is four-and-a-half meters wide and two-and-a-half meters high. There will also be two-by-two-meter paintings from my Spring series.

As for the theme, in Greek mythology, Gaia is the goddess of the planet, of life, and is the embodiment of nature. As mentioned before, I like to be inspired by the wonders and gifts of life that nature presents to all of us. Therefore, my works will resonate strongly with the name and spirit of this Biennale. My art can also be interpreted as a tribute to our living, breathing planet and all the grandeur Gaia has to offer.

Camilla Alvarez-Chow is an editorial assistant at ArtAsiaPacific.