People

Wu Jian’an Crafts Mythologies of Today and Tomorrow

Myths as future, future as myths—Wu Jian’an creates a powerful magnetic field that connects the ancient to the future through various media, encompassing paper cutting, oil painting, and installations using taxidermy replicas of animals and multiple other materials. He has delved into Chinese myths from the ancient book of Classic of Mountains and Seas and revealed the energy and sorrows behind these seemingly horrifying and sensationalist tales. For example, the ancient story of Xingtian has recurred in his works: Xingtian’s head was cut off by the emperor and he took revenge with his dead body out of deep desperation. Such primitive urges are echoed in Wu’s obsession with animal figures—but not animals in reality or animals in a biological sense. For him, animals are mysterious beings that can awaken our ancient memories rooted in human genes from millions of years ago. In his 2016 exhibition “Omens” at the Beijing Minsheng Art Museum, abnormal-looking animals—including a tiger with nine heads and a spotted deer with eyes on its hind legs—are messengers from God, giving a glimpse into our future. I spoke with the artist about the animal themes in his works, his revelations about Chinese culture through its mythology, and his contemplation on humankind’s future.

At the festival Art Field Nanhai Guangdong 2022, your work The Ocelot and Its Friends (2022) was set in the abandoned village of Huanggang. What were your considerations for this setting? Is this setting—one of human ruins amid a jungle—meant to be the leopard cat and his friends’ birthplace or homecoming destination?

The aim of Art Field Nanhai Guangdong 2022 was to draw the attention of urban people to the countryside and villages. To a certain extent, the art is second to rural revitalization. When I went to see different locations, I was stimulated by the environment of Huanggang village. It is like a modern-day Angkor Wat without Buddhist interventions. It was hot there. The banyan trees and other tropical plants were growing into the masonry like plasticine, enveloping all traces of human presence and turning the architecture into a part of nature. Surrounding plants possessed a similar vitality. They took root in the smallest of empty spaces and grew up to two meters in height, collapsing these decaying buildings in the process. I was impressed by the strength and tenacity of plants and I came up with an exciting idea: the power of people and plants form a kind of tug-of-war, a dialogue that spans time. When humans came and built the house, the plants receded for a while, but when people moved out of the village, the plants covered civilization again. When we do art projects, we are also competing with plants for resources. Human beings always move fast, but plants grow in cycles and recover slowly. It is a long and slow, mutual evolution.

The leopard cat, a small- to medium-sized feline, is a protected species in Foshan. The idea of my work is that when Noah’s ark came to rest and the earth opened its arms to animals and humans again, the leopard cat brought his friends on Noah’s ark to visit his homeland. Most of the animals in the project are in pairs. The metaphor of the flood can be interpreted in many ways, perhaps as reflective of the human population, natural disasters, or even a virus. Only when floodwaters recede can animals and plants return to the earth.

Another of your works at the Art Field Nanhai Guangdong 2022, Old Man Ding Moving Home (2022) is a play on language, one caused by the difference between the Chinese spoken in northern and southern provinces. The humorous, worldly nature of this work is a marked departure from the darker themes of your earlier projects. What drew you to the figure of Old Man Ding?

Old Man Ding is a common children’s game in northern China. You sing a rhyme, and you draw the image of “Old Man Ding” following the lyrics. My wife likes to draw Old Man Ding wherever she goes—I don’t know why! When we visited Nanhai for our research, I wondered what it would be like if Cantonese people drew this, but it turned out that there was no such game in Guangdong province. I think there is something behind this: the steps to draw Old Man Ding are rhymed in the northern song. If you translate it into Cantonese, the number of words changes and this jumbles the rhyming system. For example, the northern name for Old Man Ding is “ding laotou” [three characters] and the Cantonese name is “ding1 baak3” [just two]. The song would have to be modified for a Cantonese audience to take hold in the local community. One of my students from Guangdong helped me convert the song into Cantonese rhymes. In fact, it is a migration of language. After China’s reform and opening up, many people from the north came to Guangdong to earn money and start their own businesses, and I think they are all like Old Man Ding. Guangdong culture has a strong regional identity, but it is also very inclusive, like the soil—all kinds of things can come and grow.

Many of your sculptures and installations in recent years have featured hyperrealistic animal specimens. What are the unique features and technical difficulties of this material? Why did you begin using animal themes in your installations?

The technical difficulty in creating replica animals specimens lies in the face. It’s easy to simulate bodily fur, but not facial fur, especially that on the nose which grows in different lengths and directions. From the nose you can tell at a glance whether it is a real animal or a simulated specimen. There are fabricators in Fujian province with workers specializing in tiger replicas, but I usually work with a friend who specializes in animal specimens and often collaborates with numerous scientific researchers.

Our relationship with animals is deep and mysterious. When animals appear, some of your intuitive and instinctive energy is awakened. Just as we humans do not know where we come from, who we are, and where we are going, animals are not clearly defined—and perhaps never will be. In the 2016 exhibition “Omens,” the animals are letters from God, and their bodies carry mysterious messages from God. Later in the 2018 show “Of the Infinite Mind,” those animals are meant to be human-made objects: animal specimens and sculptures made by humans. Real animals are not made by men, but by God, or they are the natural products of evolution.

The human act of creating animals is another force that impacts the world. The moment humans wanted to create animal specimens, a certain intention arose: to be like God. Then humans wanted to create artificial intelligence. Our subsequent fate is written, and we can only follow the script. In The Ocelot and His Friends, the animals are not animals in the zoological sense, but symbols in narratives.

In your work Through the Messenger (2018), you encased yourself in a huge, heavy animal costume. What were you trying to convey about the relationship between humans and animals?

It was a strange piece of clothing for a human, made from animal materials such as horse hooves, horse tails, and sheepskin—a bit like a centaur in mythology. I put on the animal-skin suit, poured a lot of ink on it, and thus I became a huge brush, rubbing myself on a large piece of paper. It was in the summer, and the animal skin was thick and tight on me, completely impermeable to air. With lots of ink absorbed into the hair, the whole suit was over 200 pounds. I had to step on the horse’s feet, like on stilts. I couldn’t even stand up by myself. Then several people used steel wires to hoist me up, like they were suspending a martial arts actor. I was totally stunned and couldn’t breathe as the steel cables strangulated me. My arms and legs just flailed desperately at whatever was within reach. This semi-uncontrolled state was brought about by the collaged body of a half-human and half-animal. Its consciousness and initiatives came from me as a human, but it acted under the constraints given by the animal. The human body and the animal skin were competing with each other, leaving traces on the paper, like symbolic signs and omens.

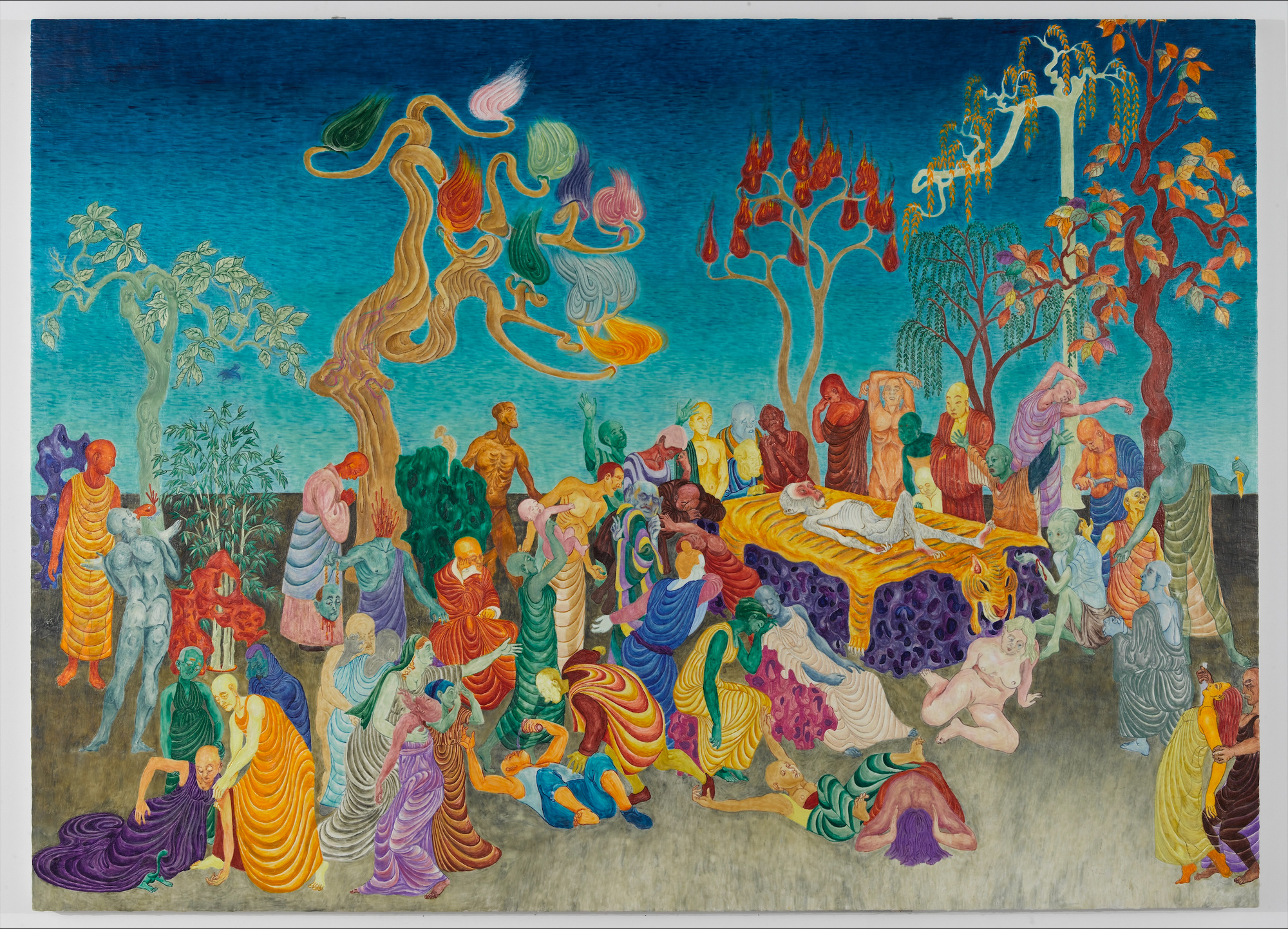

Your painting Nirvana of the White Ape (2014) depicts 49 people, who conspire to lead a white ape into the state of nirvana and was originally inspired by the 16th-century story Journey to the West, one of the four classic novels of Chinese literature. In the original story, the Monkey King has a strong rebellious spirit, but was eventually disciplined and put on the “right” path as a disciple of Buddha. In what ways did you want to present Journey to the West in your work?

I was born in 1980, and my generation was greatly influenced by the Journey to the West television series. The beginning of the series is particularly memorable: with a sound of “dong,” a stone explodes and the monkey flies out with a “bang”—like the beginning of everything. The original text does not include the bang, but only mentions how a stone, after absorbing the universe’s energy, becomes the monkey. I think the director of the Journey to the West television series was quite remarkable for creating such a startling beginning—a living thing is born out of an explosion.

I imagined what if the beginning of Journey to the West is not life but death, and from death it comes to life again. In Nirvana of the White Ape, I made up the posture of the monkey—who reclines on a bed—surrounded by 49 other characters from canonical paintings in art history, both Chinese and Western, such as works by Albrecht Dürer, Lucian Freud, and Jacques-Louis David, as well as Li Song’s Skeleton Fantasy Show. I kept their postures from the original paintings but changed their clothes, as if the main characters in the original paintings came here to play supporting roles. And their postures generate new meanings in the new scene. It’s kind of like the entire canon of art history is forcing the White Ape to die. But the White Ape symbolizes the hope of everything—he will come back after death.

Many of your works, such as The Heaven of Nine Levels (2008) and Xingtian (2006–07), expressed a sense of “spiritedness” and great imagination in ancient Chinese myths. But Chinese culture could also be very self-limiting. For example, Confucius deleted parts of Shi Jing (The Book of Songs) and the legend stories of later generations were somehow disciplined by Confucianism. How do you view these underlying tensions? In your opinions, how do the “spiritedness” in ancient Chinese mythology function in the modern society of China?

I think there is a key image to illustrate this question: Xingtian, the most unyielding figure in Chinese ancient mythology. He opposed the Yellow Emperor. While others surrendered, he did not. He continued to fight with the Yellow Emperor, but was defeated. The Yellow Emperor cut off his head with his sword and buried it on Mount Changyang. When Xingtian couldn’t find his head, he turned his torso into his face and grew two eyes on his chest. His corpse jumped and continued to fight with Yellow Emperor.

I think the image [of Xingtian] is like a safety harness. Confucianism has a clean, shiny surface on the top, fragile and vulnerable. Of course, it is important, but when it comes to moments of crisis, Xingtian is awakened within us, with an unyielding sense of “spiritedness.” Even if there is no hope, with only the corpse left, it will continue to fight. It reminds me of the accounts from the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, when the Kuomintang army was defending Shanghai in 1937, and the Chinese soldiers were so poorly equipped that they couldn’t beat the Japanese tanks so they bundled themselves with explosives to blow up the tanks.

Nirvana of the White Ape was presented in the group exhibition “From Confucius to Christ” at Yeh Art Gallery in New York last year. Did the dialogue with different religious systems such as Christianity inspire any new feelings or thoughts in you?

My understandings for religious studies are rather surface-level, but I do have a special admiration for Buddhism. In around 2012, I went to see the Buddhist sculptures in the Lower Huayan Temple [in Datong, Shanxi province] dating from Liao Dynasty (907–1125). The whole space there formed a [spiritual] field. You would perceive them as sculptures when you view them from a standing position; but when you crouch, the two figures then morph into something much deeper than what we traditionally understand as “sculpture.” There were heavenly kings on the sides, all with fierce expressions and angry eyes. Their eyes fixed on my back, forming a line of defense behind me. Four bodhisattvas sat in the middle, two on the outside looking at me with a gentle gaze, and two on the inside looking one step in front of me. My gaze followed the bodhisattvas’ and was guided forward and upward to the eyes of the Buddha in the middle. The Buddha was not looking at me but at a distant place. But I knew he would see me in his peripheral vision. In that moment, I felt that Buddha would take me far away with his gaze, and I didn’t have to worry about anything—just leave it to him.

This kind of work that concerns the entire of the space is nurtured by the wisdom of Buddhist beliefs. I used to think very shallowly about art, about shapes, lines, colors, and so on. After this experience, I realized that there is a particularly deep field waiting for me ahead.

Your work Pegasus Odyssey (2021) is the story of a young orange horse who dreams of flying to the moon, incorporating traditional Chinese shadow puppets. Why did you use this approach to the Odyssey?

The project was commissioned by Hermès, whose logo is orange, so we made an orange horse. Hermès is concerned with passing on traditional handicrafts, and I was very excited when they wanted to see if there was a possibility of linking the project with traditional shadow puppetry. I had done a lot of leather carvings with the shadow puppetry carving techniques, but they couldn’t move. So I was very excited when I could make shadow puppets to stage a real drama. The ore pigments used in traditional Chinese art do not transmit light, so even though the traditional shadow puppets are also colorful, the choice of colors was limited to red, copper green, gamboge, and black. But industries these days, especially that of acrylic paints, offers transparent colors that are bright and saturated, so our shadow play looked very good.

Would you ever consider incorporating other cultures’ mythologies into your future artworks?

Possibly I will. Many ancient myths from different civilizations may have told the same original story, but have morphed during transmission, as if our stories are ours and European stories are theirs. Europe tells the story of Noah’s ark; China tells the story of Yu the Great taming the floods and Nüwa mending the sky. But what our common ancestors experienced might have been the same, but as they told the stories, it became different versions. Mythology has the potential to reunite civilized humanity in this divisive confrontation.

If human civilization died out and only the records of civilization remained, which of your works do think would be most attractive to, say, non-human civilizations?

I think it will be the petroglyphs of Lascaux, Altamira, and Tassili, et cetera, that attract these aliens. What happened to the human species that they chose to behave in this way, to paint visually recognizable colors on a surface and to depict the three-dimensional world they saw? And the petroglyphs can survive for a long time. What makes a human-being human is probably the fact that we paint, which is the first and last letter we leave to the world. My works may not be qualified, but my ongoing series 500 Brushstrokes (2016– ) contains something very primitive. A human’s simplest arm movement leaves behind a self-portrait and a projection of their past experience. So when aliens see such paintings, they can see not only an individual but also a collective.

Freelance journalist Qin Wang was previously an editorial intern at ArtAsiaPacific.