People

The Essential Works of Shigeko Kubota

“I want to create a fusion of art and life, Asia and America, Duchampiana and Levi-Straussian savagism, cool form and hot video,” explained Shigeko Kubota about her work in 1979. Born in 1937, in Niigata, Japan, Kubota had met John Cage and Yoko Ono at a 1962 performance in Tokyo and jumped at the chance to live in New York in 1964 when Fluxus founder George Maciunas invited her for a performance. She gradually became a regular figure in the Fluxus community, and Maciunas described her as the collective’s “vice president.” In the 1970s, she picked up a Portapak camera and began creating her most well-known diaristic works, exploring the new media of video installation, her artistic relationship to Marcel Duchamp, as well as her personal relationships with her husband, Nam June Paik (1932–2006), and her father. Kubota showed widely in her life, including at iconic New York venues, from Rene Block Gallery (1976) and The Kitchen (1984) to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1979 and the Whitney Museum of American Art, which surveyed her work in 1996. Her first major survey back home, “Viva Video! The Art and Life of Shigeko Kubota,” is currently at The Niigata Prefectural Museum of Modern Art, and will tour to The National Museum of Art, Osaka before ending at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo next February. Here’s a look at some of Kubota’s most influential works.

Vagina Painting (1965)

For her first (and only) performance during the Perpetual Fluxus Festival at New York’s Cinematheque in 1965, Kubota waddled across a large sheet of paper with a paintbrush attached to her underwear. The resulting red strokes and smears alluded to menstruation, as well as the performances of geishas who would write calligraphy with their vaginas to entertain their guests. While the piece appears to be a feminist response to the action paintings by male figures such as Jackson Pollock, who were at the center of abstract expressionism, Kubota did not characterize her works as “feminist” and did not believe that art has a gender.

Europe on ½ Inch a Day (1972)

Kubota’s spontaneous video documentary—one of the earliest travel vlogs in the world—depicts an adventure through Europe, as she explored what it would be like to travel without even five dollars, but instead a ½ inch Portapak. Accompanied by cheerful carnival music, the moving images capture subcultures in the 1970s, such as a Parisian sex cabaret and a gay theater troupe in Brussels, with an unfiltered curiosity. Viewers are brought along with Kubota as she blends in as an observer. The journey concludes with a homage to Marcel Duchamp, who passed away in 1968.

Marcel Duchamp’s Grave (1972–75)

Kubota met Duchamp for the first time in 1968, on a flight to Buffalo, New York, where they were both participating in a performance. The encounter ignited Kubota’s fascination with Duchamp’s groundbreaking approach to conceptual art. First exhibited at New York’s The Kitchen in 1975, this installation comprises edited and colored footage from Kubota’s visit to the Duchamp family graveyard in Rouen in 1972. The only subject matter visible to the viewer is the interplay of light and wind, and the silhouettes of a shadowy grave. Silence is punctuated three times by Kubota chanting “Marcel Duchamp, 1887 to 1968.” Throughout her life, Kubota would draw from him as an inspiration while creating a legacy entirely her own.

Duchampania: Nude Descending a Staircase (1976)

In the 1970s, Kubota created a series of video-sculptures dedicated to Duchamp. One of these works is her reinterpretation of his iconic painting of an abstracted figure in motion, where several moments in time are depicted within one frame. Then based in New York, Kubota filmed a nude female filmmaker descending into the lobby of a hotel in Manhattan. The looped footage is played on four television screens, each encased in one step of a plywood staircase. The wooden casing began as a quick solution to unwanted brand signage on the devices, but Kubota also saw it as an organic way to fragment images and splice time, just as Duchamp had. The work was well regarded at Documenta 6 in 1977, and was purchased by curator Barbara London as the first video-sculpture in the collection of MoMA.

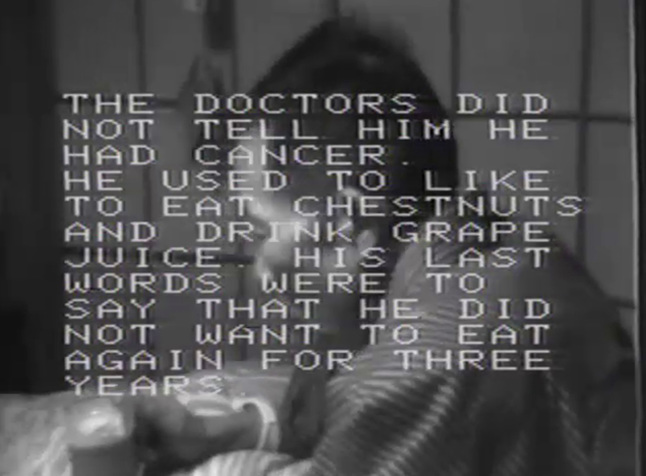

My Father (1973–75)

This 14-minute black-and-white video records the last days of Kubota’s father, who was suffering from cancer. In one of the clips, Kubota watches television with him on New Year’s Eve. Her father appears solemn as the television blares a melodramatic musical performance. This cuts to footage of Kubota weeping alone in front of the monitor after his death. Utilizing video to preserve the presence of her father and release her grief, the artist connects with audiences through an intimate portrayal of losing a loved one.

Rock Video: Cherry Blossoms (1986)

Pale pink cherry blossoms and a clear blue sky are deconstructed and obscured in this 13-minute kaleidoscopic video. An electronic mutilation of natural spatial boundaries and imagery, the work exemplifies Kubota’s signature transfusion of the organic with the artificial, an approach that she started in the late 1970s. The silent video was installed on New York’s Times Square billboard to mark the 40th anniversary of the nonprofit organization Electronic Arts Intermix in 2011, and on the West Manhattan High Line in 2014.

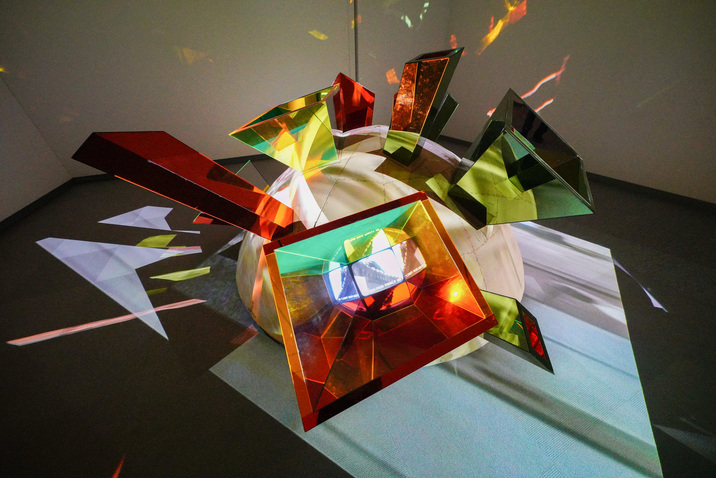

Korean Grave (1993)

Inspired by her trip to South Korea with Nam June Paik in 1984, Korean Grave is Kubota’s loving tribute to her husband, who was visiting his native country for the first time in 34 years since his migration to the United States. The dome-like installation has protruding, mirrored lenses through which viewers can watch clips from Kubota's video Trip to Korea (1984), of Paik visiting his ancestral graves with family members. Recalling traditional Korean burial mounds, the video installation layers loss and reconnection, death and spiritual revival.