People

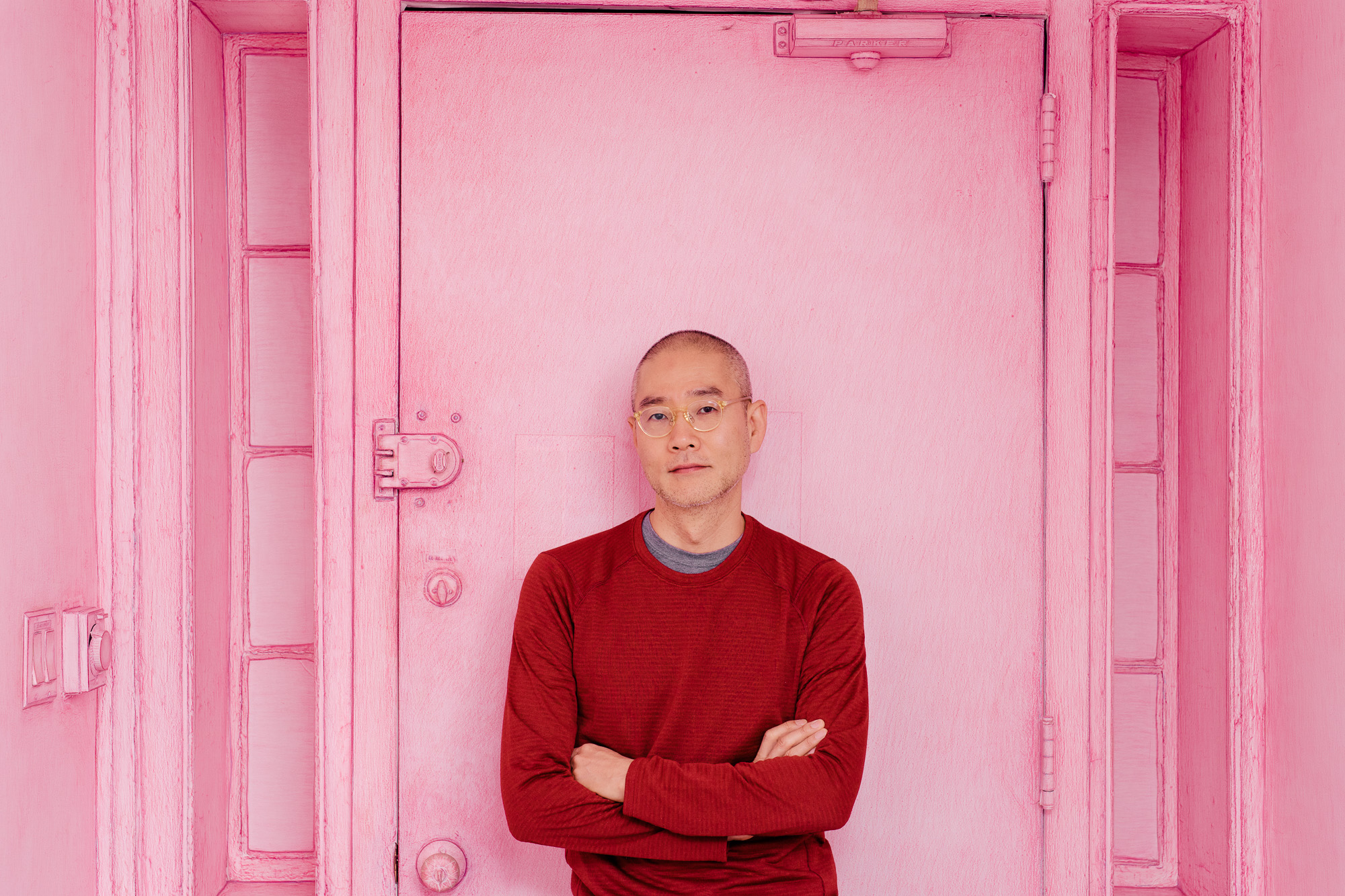

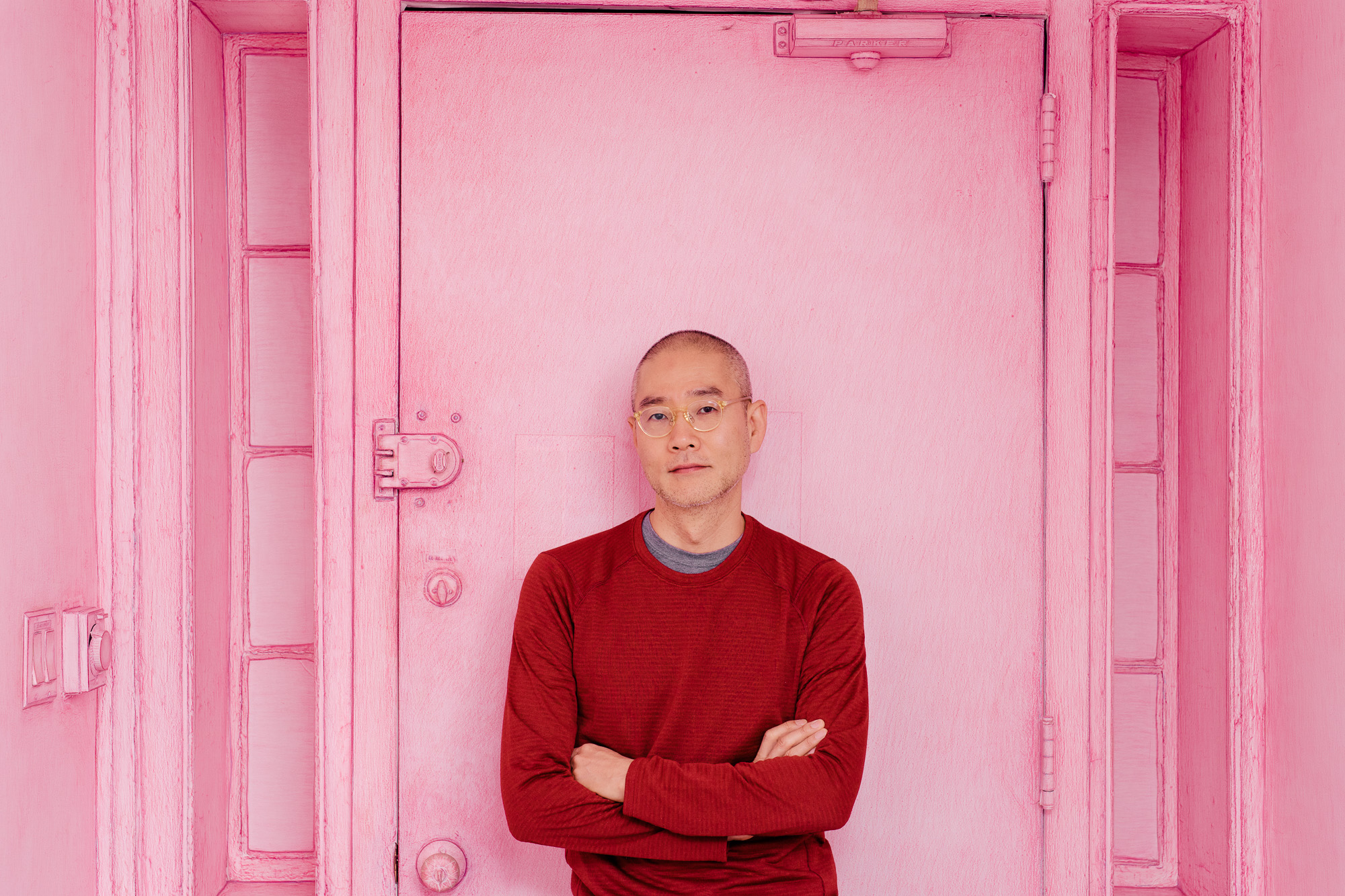

The Essential Works of Do Ho Suh

Korean artist Do Ho Suh’s installations, sculptural works, and two-dimensional pieces inspect the individual’s conceptualization and contextualization of home, migration, and memory, philosophizing on the impermanence of temporal and spatial conditions. His most notable installations, created in translucent polyester, silk, and nylon fabrics, are huge reconstructions of spaces in which he has lived throughout his life. Perhaps influenced by his own lived experiences, his later artworks are manifested as not only mature, logical progressions of his work on permanence, but also meditations on the individual’s power to forge their own paths.

Suh has widely exhibited within South Korea and the United States, as well as other international art institutions such as London’s Tate Modern, the Singapore Art Museum, and Helsinki’s Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art. In 2001, the artist represented South Korea in the 49th Venice Biennale. On the occasion of his solo show at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia in Sydney, here are nine of Suh’s most iconic projects throughout his three decades of practice.

High School Uni-Form (1997)

During the Japanese colonial rule of Korea from 1910 to 1945, the empire’s influence could be found even in the minute aspects of Korean culture. The gakuran—a dark set of men’s uniform with a high collar and gold buttons—was introduced into Korean high schools. High School Uni-Form is one of Suh’s oldest works, comprising rows of 300 gakuran aligned in a grid-like pattern, all sewn together at the shoulder seams. Reminiscent of a morning assembly, a graduation ceremony, or even a quasi-military exercise, the uniforms’ invisible owners are made to be quiet, orderly, and obedient. The individuality of these “ghosts” is repressed, since their presence is only acknowledged by the uniform they wear. Questioning the idea of collectivism in the Korean context, the work also reflects how men transition from one uniform to another, as male citizens aged 18–35 in Korea are required to partake in mandatory military service. While the Korean gakuran is modeled after those used by Japanese students, the style of uniform is German in origin, casting a subtle fascist undertone in the work.

Public Figures (1998)

Public Figures is Suh’s first and only public art piece. Set up in a park in Brooklyn, the work comprises a white stone plinth, supported by the outstretched arms of hundreds of miniature fiberglass-and-resin figures underneath. Challenging the static and permanent nature of the monument, Suh originally intended to move the sculpture inch by inch through a built-in mechanism every day. While this plan was rejected on the basis of safety concerns, Public Figures serves to question our practice of placing illustrious and canonical figures on pedestals, and testifies to the gradual social progress made possible by the efforts of the nameless masses. Suh wrote that the piece represents “the multiple, the diverse, the anonymous mass . . . supporting and resisting the stone. Public Figures is almost an anti-monument; it brings the statue down from the pedestal.”

Seoul Home/L.A. Home/New York Home/Baltimore Home/London Home/Seattle Home (1999)

When Suh made the career-defining move to New York following his graduation from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), he became so riddled with insomnia that he started thinking about his bedroom in Seoul. At that moment, he “wanted to bring the house, somehow, to [his] New York apartment.” In 1999, Suh created Seoul Home, an up-to-scale reconstruction of his home in silk. Without the protection of opacity, the boundary between personal and public space also dissipates. The light celadon color of the silk is a nod to the ceiling paper in a traditional Korean study room, which is colored to symbolize the sky, facilitating the scholars’ contemplations on the universe during their studies. Foldable and lightweight, the portable installation later became the first of Suh’s signature fabric installations. As an extension of the artist, Seoul Home is able to frequently uproot itself and settle in new places, reflecting his identity as an itinerant traveler, and bringing his culture and “home” along wherever he goes. Taking on an additional location name wherever the installation travels to, this work came to be known as Seoul Home/L.A. Home/New York Home/Baltimore Home/London Home/Seattle Home.

Staircase (2003)

As Suh settled in New York, his textile installations took on a more abstract and symbolic turn. Created for the 2003 Istanbul Biennial, Staircase is one of his first extensive experiments with this now iconic motif. Like Seoul Home, the work is modeled after a space from his personal history, which is, in this case, the staircase in his New York apartment. As a channel to transport oneself between two spaces, the imagery of the staircase further magnifies the psychological and spatial displacement one experiences from viewing the work. Staircase is created with a translucent, vermillion nylon fabric and attached to two stacked “ceilings” of the same material, suspended in mid-air. Visitors had to walk cautiously around the base of this life-sized partial replica of the artist’s home. Staircase reveals to us the physically minimal but psychologically influential ambiance of architectural space.

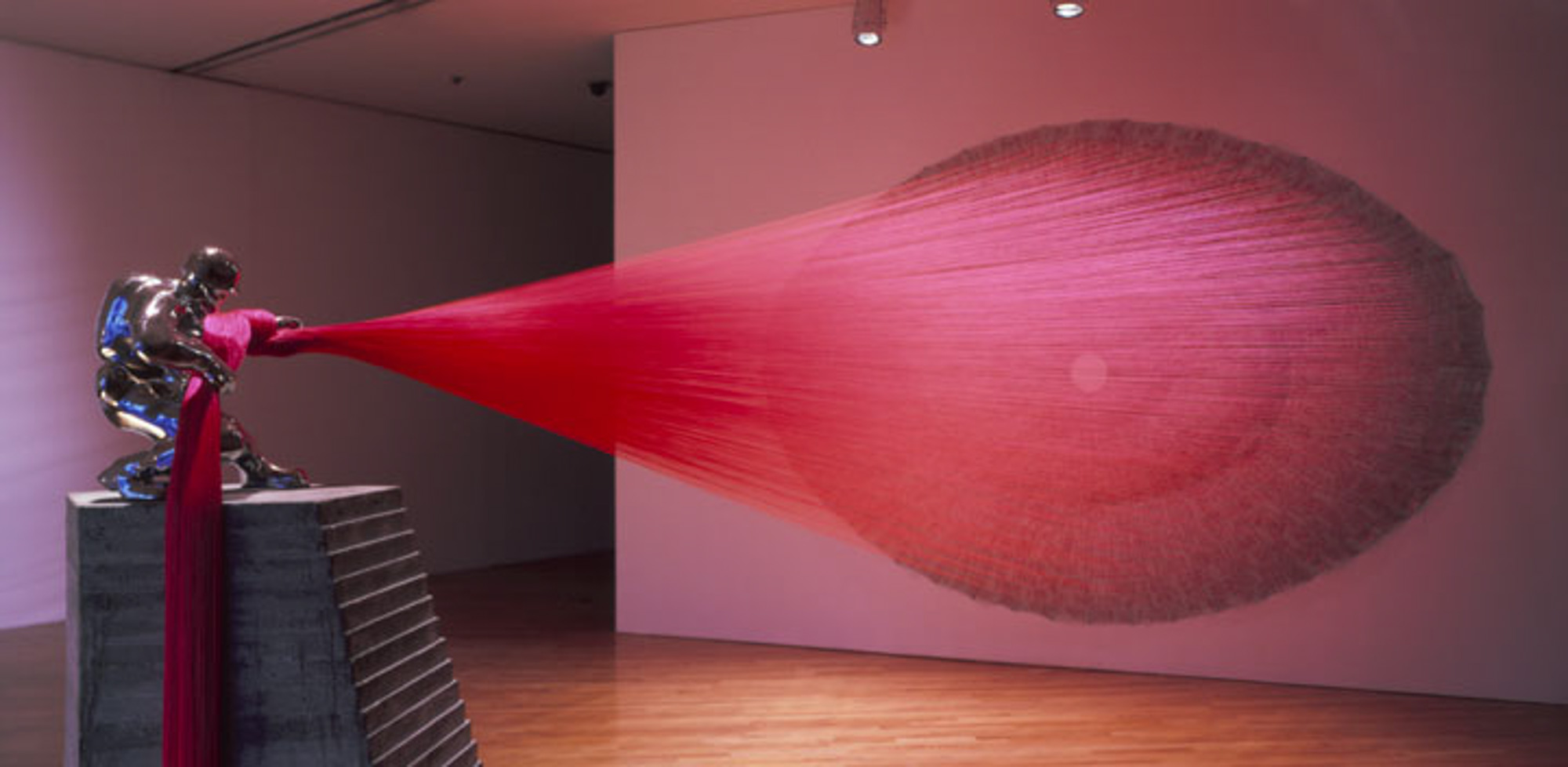

Paratrooper-I (2003)

Paratrooper-I is the first of Suh’s Paratrooper series (2003– ) of sculptural installations. In preparation for the work, Suh collected the signatures of some 3,000 family members, acquaintances, and friends from personal journals and exhibition guest books, then hand-embroidered them onto an elliptical piece of linen. Red polyester threads extend from these names onto a raised concrete platform, where a reflective steel-like paratrooper gathers these fibers into his arms. The paratrooper appears to be tugging on these threads, as if he is trying to collect a caught parachute. Working in two different directions and against each other, the tension between the figure and the fabric appears palpable at first glance. According to the Lehmann Maupin gallery, where the work debuted, “the paratrooper acts as a metaphor for being dropped into and surviving amidst a new environment, and thus, his reliance on his parachute for a safe landing is key.” The piece gives visual expression to the power of the collective, connecting the isolated paratrooper to thousands of individuals.

Home Within Home Within Home Within Home Within Home (2013)

By 2013, Suh had delved into fabric and textile art for over a decade to express his feelings of displacement and unfamiliarity as an Asian immigrant. Such works often emphasize the discomfort that arises from the dramatic spatial change he experienced, having to adapt to his many different homes. Home Within Home Within Home Within Home Within Home, however, is not only a revisit of this oft-explored concept in Suh’s oeuvre. For Suh, Home Within Home marks an intersection in his identity: a crossroad where the past and the present, as well as the West and the East, clash and meet. With the help of a 3D scanner, Suh created a 12-by-15-meter replica of his three-story home in Rhode Island, where he lived as a student studying at RISD. Viewers can walk into the fabric house to see a smaller replica of a hanok, the traditional Korean house where the artist grew up. Both structures are made with a lightweight polyester material, which Suh described as “cheap and readily available.”

%2001%20hr.jpg)

Rubbing/Loving (2013– )

Departing from his approach of placing faithful replicas of physical locations in art spaces, Rubbing/Loving takes the concept of site-specific installation to a more extreme definition. Rubbing/Loving is a full-scale, colored-pencil-on-paper facsimile of Suh’s former apartment of 18 years. The process begins by wrapping each and every surface with white paper, covering the walls, furniture, light switches, house keys, and even the bathroom sink plug. Suh then carefully rubs color pencils across the paper sheets, preserving the minute details of the house and its “layers of time” in saturated colors. The work pays homage to the art of frottage, a surrealistic and so-called “automatic” process developed by Max Ernst to reproduce the exact particulars of a surface on paper. By highlighting the details of the apartment, Rubbing/Loving shows the space’s importance in not only Suh’s personal life but also his artistic career, as it has become the subject of countless works and installations over the years.

Karma Juggler (2015)

In 2009, Suh began experimenting with embroidery on paper, thereby merging the areas of drawing and handicraft, as well as two- and three-dimensionality in art. This process kickstarted the artist’s long-term partnership with the Singapore Tyler Print Institute, which provided resources for Suh to create more complex and ambitious “drawings.” While thread and fabric are already present as sculptural materials in his repertoire, these innovative textile drawings conform his earlier installations onto flat surfaces. Recalling his earlier ideas about interpersonal identity and boundaries, Suh redefines the term “karma” as an idea that individuals can support, alter, and affect the lives of countless others, through channels such as language, ethnicity, history, and even family. In Karma Juggler, the blue threads all seem to originate from a tangled mass in the left-hand corner of the composition, vaguely forming the silhouette of a standing man. These “karmic” threads extend outward and unravel into a spiral—swirling and merging together—representing not only reincarnation, but harmony with ourselves and others, visually expressing the ripples of karma that follow us throughout our lives.

Bridging Home, London (2018)

Co-commissioned by Art Night and Sculpture in the City, Bridging Home, London is part of Suh’s Bridging Home series (2010– ). The large work was installed on the footbridge over Wormwood Street, one of the busiest roads in London. Once again conjuring up the imagery of the traditional Korean hanok, the piece is a large-scale replica, complete with a bamboo garden. Most glaringly, the structure appears to have crashed and melded into the bridged walkway at a diagonal angle, squarely between two commercial buildings. Visitors are welcome to walk into and through this comically lopsided structure. Made of a variety of materials such as plywood and softwood, Bridging Home contrasts with the staple modernized glass and steel structures of London architecture. Suh devised the central idea of this work from his urge to investigate the migrant history in London, particularly in the East End.

“Do Ho Suh” at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia is on view from November 4, 2022.

Ella Wong was ArtAsiaPacific’s editorial intern.