People

Rewriting Monuments: Interview with Lan Florence Yee

The challenge of acquiring languages is knowing in which context a word, a turn of phrase, or an expression fits naturally. In sifting through the ambiguities that surround language usage, meaning can be reimagined, innovated, transformed, and reclaimed. Text, the semiotic carrier of meaning, is fertile for the investigation of our textualized experiences.

This is certainly the case in the practice of Toronto-based artist Lan Florence Yee, whose works incorporate signages, documents, labels, and messages between friends that direct and influence how one goes about their day. With language as their focus, in their earlier works, Yee revisits their childhood and familial memories to complicate the nostalgia of “belonging,” a sensibility common in works about the diaspora. Yee’s latest solo exhibition—“Sharper Tools for Unripe Fruits” at the artist-run center Neutral Ground in Regina—expanded their investigation by addressing the awkwardness of monumentalism, especially the significance of historical markers in public spaces, and the discrepancies between viewers’ contemporary understandings of them and the intentions of the creators. A multimedia exhibition with a public intervention, “Sharper Tools for Unripe Fruits” contributed potent strategies to the ongoing deinstitutionalization and decolonization efforts that are gaining momentum worldwide. I spoke with Yee about the role of language in their work, and how they challenge concepts of monumentalism through diverse approaches.

Your latest exhibition included a public intervention where you distributed around downtown Regina leaflets that read, for example, “Seeking: Permission to Take Break,” or “Seeking: A Place to Feel Queer.” This constant action of “seeking” in a public space acutely highlights the unequal power dynamics and prescribed relationships between the readers of these leaflets, the visitors to the gallery, and monumental structures. Can you elaborate on why you chose to assume this position as the artist, and for the viewers?

That project came out of an emerging-artist mentorship program at Mitchell Art Gallery where I was a mentor in Summer 2020. I was paired with Kiona Ligtvoet, an artist based in Edmonton. We were having conversations about how to combat institutional power both from the outside and the inside; how to support each other; and prioritize ourselves. We both make works that draw from our personal experiences, so we were also discussing boundaries between the audience and the artist, and reading A Glossary of Haunting (2013) by Eve Tuck, a researcher in Indigenous studies, and artist C. Ree.

The program happened during the deepest period of pandemic isolation. The “seeking” was a cry for some connection to others, and a way for me to reflect on what I was “seeking” in various aspects of myself, my community, my work, or even abstract ideas like seeking justice. Seeking something as intangible as justice has opened the potential for the project to materialize conceptually toward actions. The absence of a response mechanism to the posters invites others to participate without assuming what that action might look like. The public can interact by either contemplating or sharing the “seeking,” which hopefully cultivates a sense of generosity. Unlike monuments where the messages of building solidarity, boosting civic morale, or forming a collective identity often flow top-down, the Seeking (2020–21) project accomplishes those things without taking up permanent space. Instead, it allows spaces for exchanges and self-determination. The awkwardness of monumentality lies in its nonreciprocal character.

How was this exhibition a continuation of your previous projects? Were you responding to the anti-monumentalism movement that has gained much traction in recent years?

The exhibition did not start out as a response to the social movements that have erupted since mid-2020, as it was planned years in advance. However, the show interestingly opened more than a year after the removal of the statue of John A. MacDonald (Canada’s first prime minister) from a public park in downtown Regina, just a block from the gallery. With the vacant pedestal where the statue once stood and the ephemerality of the monuments in my exhibition, there is a connection between my work and the locale of Regina.

The incidental anniversary is not alien to me and my work. In fact, my art education has been marked by many national milestones and celebrations in Canada. The works created in those moments can be contextualized within those larger narratives to ask, “what does it mean to respond to something that history has shaped for celebration?”

In 2019, I was part of a research residency and the group exhibition “Absence Is Present” at the nonprofit platform Never Apart in Montréal, where I started to notice a relationship between photography and monumentality. The exhibition brought together artists, archivists, and activists to research the missing parts in LGBTQI+ stories from the Archives Gaies du Québec. The program inspired me to inquire “what makes an image worthy of an archive?”; “what makes an image queer enough for an archive?” The result of seeking the answers is the series PROOF (2020–22), which is also in “Sharper Tools for Unripe Fruits.” I reproduced photographs of public spaces on cotton voile before embroidering the word “PROOF” diagonally across the surface. I color-matched the threads to the background so that the word would be camouflaged. The letters become most visible in the shadow cast from the fabric or upon touch. The series addresses the trust and desire for fulfillment that we put into photos and archives, and how images can be inaccessible to the public when they are locked behind the gates of institutions.

Text is a recurring element in your works. How did you start incorporating words into your work? What is its relationship to the other mediums that you use, like textile, photography, and drawing?

My early practice was centered on painting. Painting and text have an overlap in signage. Having grown up in Montréal in a Cantonese-speaking family, I am trilingual, and it is normal for me to be surrounded by trilingual speakers. Hence, I am hyperaware of how certain spaces allow and prioritize certain languages, bureaucratic words, and pragmatic design. As I move around, I often pay attention to the texts and signages in my environment. That intensified when I moved to Ontario, where I found the text convention so alien. I realized texts have the potential for reproduction; they reproduce culture.

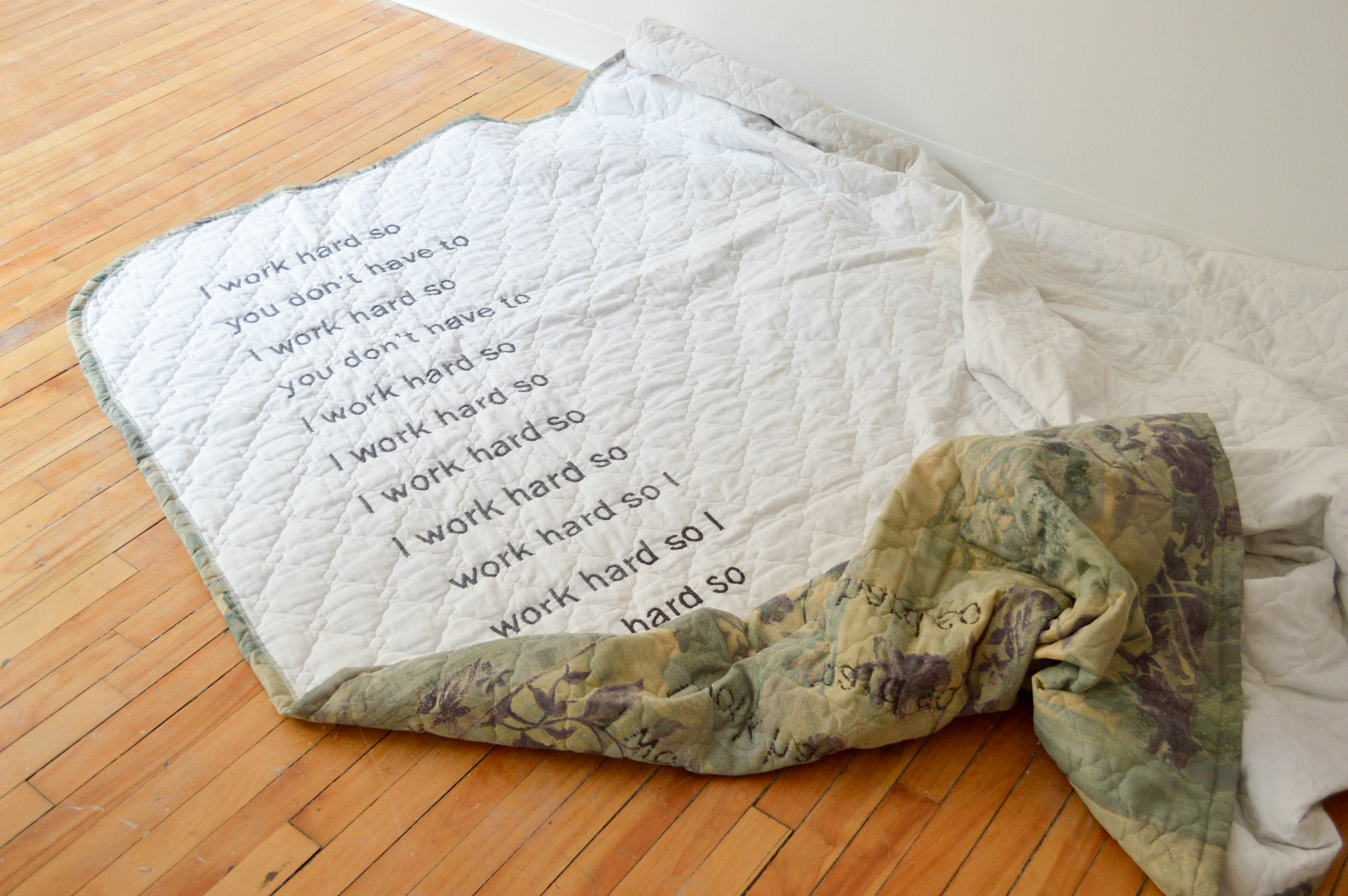

In my 2019 work A Labour of Labour, the embroidered texts are an intervention that emphasizes the ready-used and ready-made aspects of the item that they are stitched on—the blanket. The object had a previous life and a previous use before I embroidered texts on it. Like the works in PROOF or the Seeking projects, the piece embodies my interest in manual labor and time-consuming processes. Despite differences in medium, the text(ure) in all my works has a sensual, raised quality, like the works are expressing longing, and reaching out to narrow the distance between myself and the viewers.

When I was painting at the start of my career, I felt the medium was insufficient to embody my concepts materially. Text and texture come from the Latin word texo, “to weave,” and what they weave together are different narratives. I find that the works that people respond to the most are site-specific projects or multimedia works. As a work slips into other contexts or into other mediums, the reading of it is also affected, which can reveal how mundane some grand narratives are.

The slipperiness of meaning is also reflected in how you title your work. Could you share some context behind some of them?

I use titles as citations. I take inspiration for them from materials that I encounter in my research or leisure reading. Citations are ways for me to keep in my mind—and my work—thoughts and memories of people, friends, authors, and events that have informed the creation of the works. The “slipperiness” that you refer to here, I assume, is about the openness or the ambiguity in my titles. The reason behind this is that I’d like my work to occupy the space of multilingualism, of multiple possibilities, and as proof of my existence, my comprehension of different contexts. For a long time, I had to simultaneously prove my proficiency in both French and English. To the colonial authority, I am never fluent enough in either. Hence, through the titles, I want my work to easily slip and fill other things, other containers, and other people. In that sense, my act of anti-monumentality is not restricted to the taking down of monuments but also the building of collectivity.

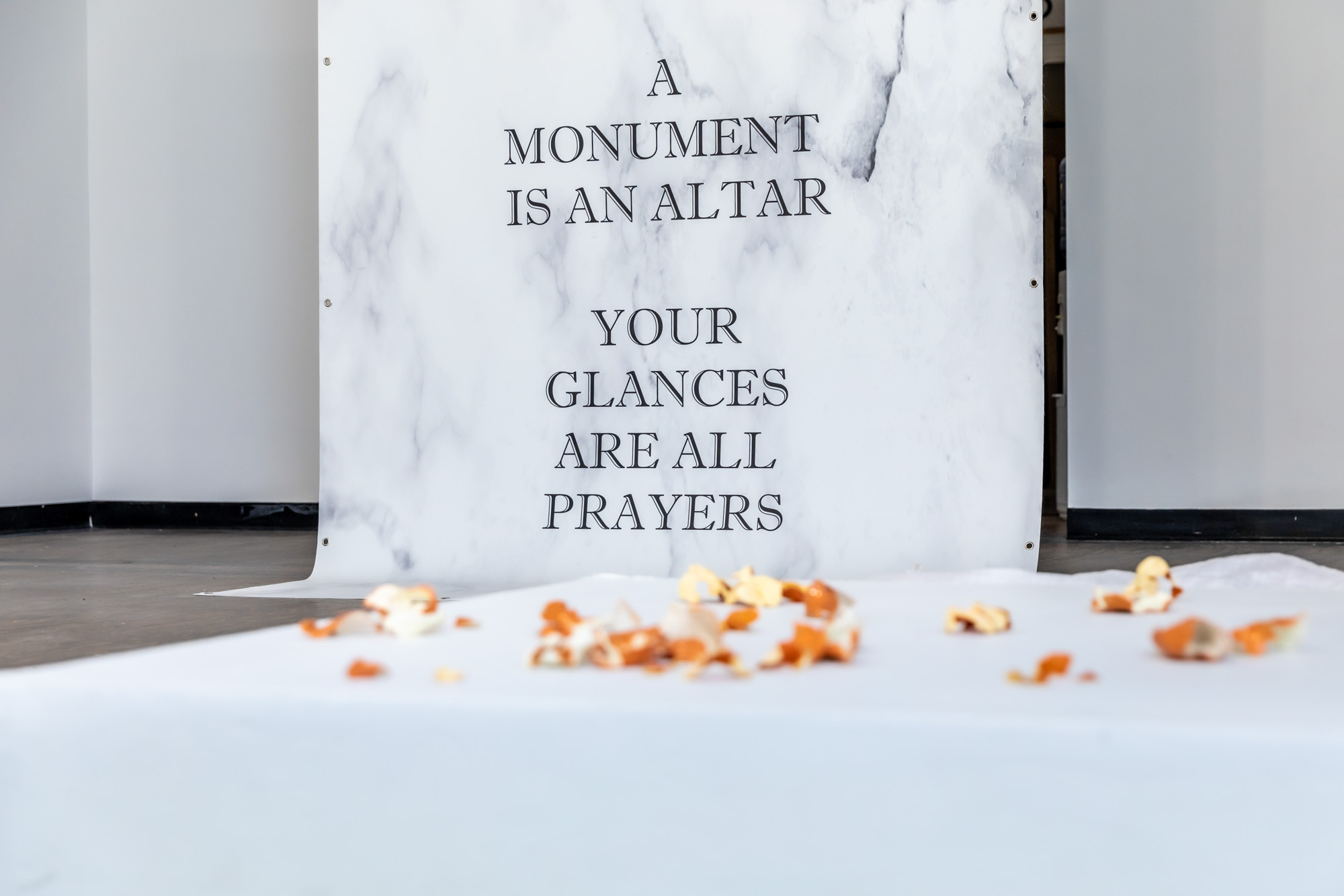

I’d like to end with a return to the most monumental work that was in “Sharper Tools for Unripe Fruits.” Pseudo-Monument (2020) is a vinyl banner that dominated the gallery space. Its text reads, “A MONUMENT IS AN ALTAR; YOUR GLANCES ARE ALL PRAYERS.” At the bottom lies a metal plaque anchoring the paper, which says, “(et. al).” What is the work about?

The work addresses the constructed and false nature of monuments, signaled by the flatness of its image. It started as a commission for the “Art in the Open” festival in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island in 2020. I made a large box and wrapped it in the same vinyl print that you saw at Neutral Ground. The work was installed in Rochford Park near a statue of John A. Macdonald, which also had a moving van with the logos of my imaginary company Monument Movers Inc. parked next to it. My intention was that as someone encountered the work on their way through the park and passed other commemorative monuments, they would keep my “prayer” in mind. The work was a soft call to action for the removal of the Macdonald statue, which was taken off the streets a few months later. The monument was not taken down by a single action, the same way it was not put up by a single action.

At Neutral Ground though, the bronze plaque functions as a footnote to the monument, bringing it back to the idea of “and more, and also, and other.” It is a reminder that my work doesn’t stand on its own. Like my distaste for monumentality, I don’t want to perpetuate the myth of the artist as a lone genius. My projects are often collaborations, but even without other people’s hands explicitly shaping the pieces, there are movements, legacies, love stories, and conversations that have made the work possible.

Lan Florence Yee's "Sharper Tools for Unripe Fruit" was on view at Neutral Ground, Regina, from June 11 to July 23, 2022.