People

Oscar Murillo Uses Artificial Intelligence to Measure “Frequencies”

During the opening weekend of “A Storm is Blowing from Paradise,” a solo exhibition in Venice of Colombia-born London-based artist Oscar Murillo, the artist brought up a curious detail. The long-running series of more than 40,000 drawings on canvas created by children around the world, Frequencies (2013– ), perhaps Murillo’s best-known project aside from his abstract paintings, is undergoing digitization and, more intriguingly, the digitalized works will then be analyzed using forms of artificial intelligence.

The juxtaposition between the contemporaneity of artificial intelligence and the exhibition’s setting in the 16th-century social charity building Scuola Grande della Misericordia, perhaps, should not have been surprising considering that Murillo pulled the title from Walter Benjamin’s 1940 essay “On the Concept of History.” In that now-famous text the German-Jewish philosopher critiqued the Marxist concept of historical materialism, the idea that history is a series of connected events that lead to progress. Specifically, the title is from Benjamin’s discussion on Paul Klee’s painting of a winged figure, Angelus Novus (1920), as a metaphor on how to view the passage of time, history, and progress. Perhaps the title was a reflection on the nature of the exhibition—Murillo’s new and older artworks sharing the same space—or perhaps, it was insight into the artist’s view of time.

Murillo first launched his Frequencies project in 2013 at Colombia Colegio Hernando Caicedo, a school that the artist had attended in his hometown of La Paila. In the schools that Murillo engages with, he and his studio cover the students’ desks with canvases for six months, allowing them to slowly record their conscious and subconscious thoughts and forms of self-expression. They don’t provide any instructions or materials. The students are between the ages of 10 and 16, as Murillo believes that they are still “pure” at this age. Through this longitudinal process, Murillo hopes to document cultural and societal similarities and differences. As of 2022, Frequencies has been hosted in 34 countries from Argentina to Zambia.

Featured in the 2015 Venice Biennale, the ever-expanding archive of Frequencies canvases was shown at the Scuola Grande della Misericordia stacked on 12 metal shelving units. Through Docent Lab, the research arm of a mobile app that feeds collectors art recommendations generated by machine-learning algorithms, the artist and his studio have been able to use Computer Vision and Natural Language Processing software to analyze the images and texts from the canvases and interpret their meanings. Speaking to Murillo and his exhibitions manager, Marta Barina, I learned that the algorithm thus far has been fed with information such as drawings found on Frequencies canvasses, the artist’s own gestures, and data from open-source software such as Google Translate API. Murillo hopes to create his own research team to further their efforts and a multicultural team that can analyze the over 50 languages thus encountered through the Frequencies project. But what will the algorithms uncover? And why is Murillo so interested in using artificial intelligence?

Although the incorporation of AI might seem to be an odd move for an artist who is best known for his works on canvas, Murillo has always been interested in technology. The artist has been working on wearable sculptures both in the real and virtual world. A part of the Arepas y Tamales project, these sculptures are made of cotton and silk patterned with drawings pulled from Frequencies. Behind these sculptures shown in the Venice exhibition was a room that housed the installation of collective conscience (2022), an interactive video work where one can try on the wearable sculptures virtually—the result of the joint efforts of the artist, Institute of Digital Fashion, Camera Nebbia, and Docent. While still a new area of research, references to AI crop up in some of Murillo’s works from Flight Drawings (2018–19) where he scrawled “AI AI AI” over and over across the page.

The application of AI in art is not an entirely new concept. In 2018, Christie’s New York auctioned a portrait of a fictional family member created by an AI algorithm designed by a French collective named Obvious who fed the system 15,000 portraits created between the 14th and 20th centuries. In September 2022, an entirely original AI-generated artwork, Théâtre D’opéra Spatial (2022), won first prize at the Colorado State Fair. The controversial artwork sparked discussions spanning from what constitutes art to the “death of artistry.” AI art generators such as DALL-E and DALL-E 2 by OpenAI and Midjourney have been gaining traction, and distorted AI art have been cropping up on social media. These forms of AI in art have mostly focused on artwork creation and whether a program can create something that approximates art.

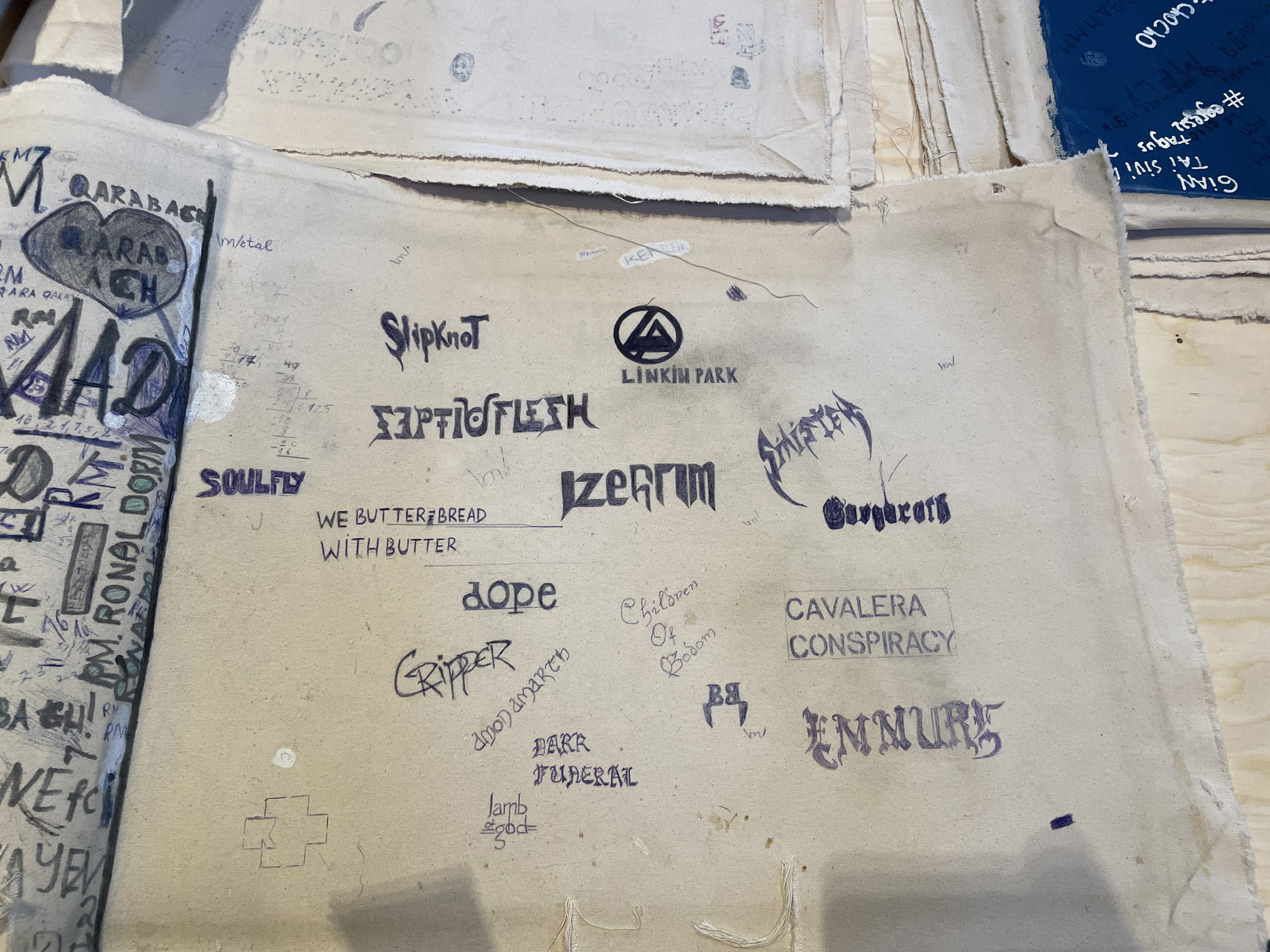

Murillo’s vision for the role of AI in his oeuvre, however, feels different. Rather than using AI to help him generate artwork, he is using artificial intelligence to understand the modern human experience of coming of age. Upon seeing that the thousands of Frequencies canvases are organized by nation, I wondered what the AI will be able to tell us about childhoods across the world. Although it would have been impossible to see every canvas, the exhibition functioned partially as a library where one could ask an archive assistant to show you canvases of your choosing. What struck me, for example, was one canvas from Baku, Azerbaijan, that had a logo of the American band from my middle-school days, Linkin Park. Is the ever-globalizing reach of American pop culture exports homogenizing the childhood experience? On the other hand, I saw a handful of canvases from schools in China, where the canvases were primarily written in Chinese, and the only symbol of globalization was the occasional Hello Kitty doodle. What is unique to each nation?

Since Frequencies launched almost a decade ago, I also wondered how the AI will account for the years in which these canvases were produced. Surely, one’s childhood from 2013 would vary from one from 2016, or mid-pandemic 2021, for example? But then again, referring back to the origins of the exhibition title, would it even be important to look at it in a chronological manner? Or do all the canvases exist in the same vacuum of time that is intrinsic to childhood itself?

As the artist continues to experiment with AI, future developments will be presented both in-person at exhibitions and online at www.arepasytamales.com. I, for one, am curious to what AI can tell us about all those years spent in school, doodling in notebooks and on desks, hoping for the school to be blown away by a storm from paradise.

“A Storm is Blowing from Paradise” is on view at Scuola Grande della Misericordia in Venice through November 27.

Tiffany Luk is associate editor at ArtAsiaPacific.