People

No Time Like Passing Time: A Conversation with Tehching Hsieh (Part 2)

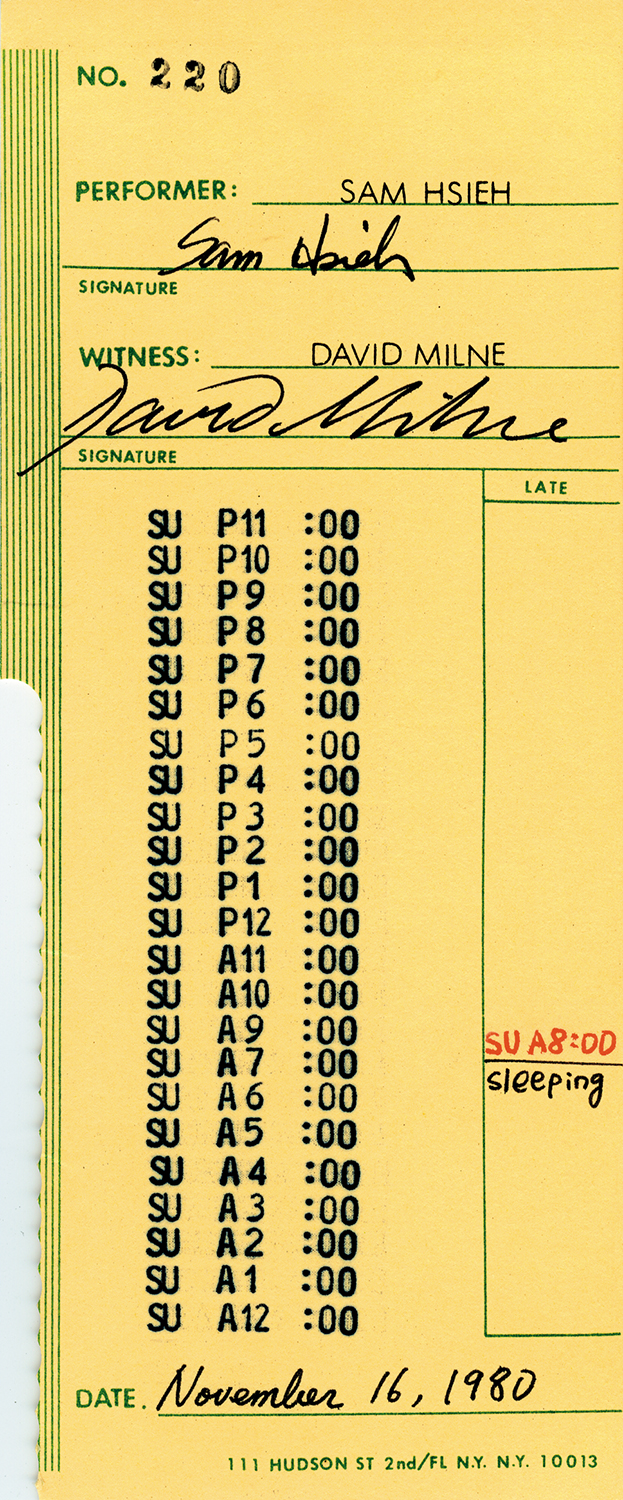

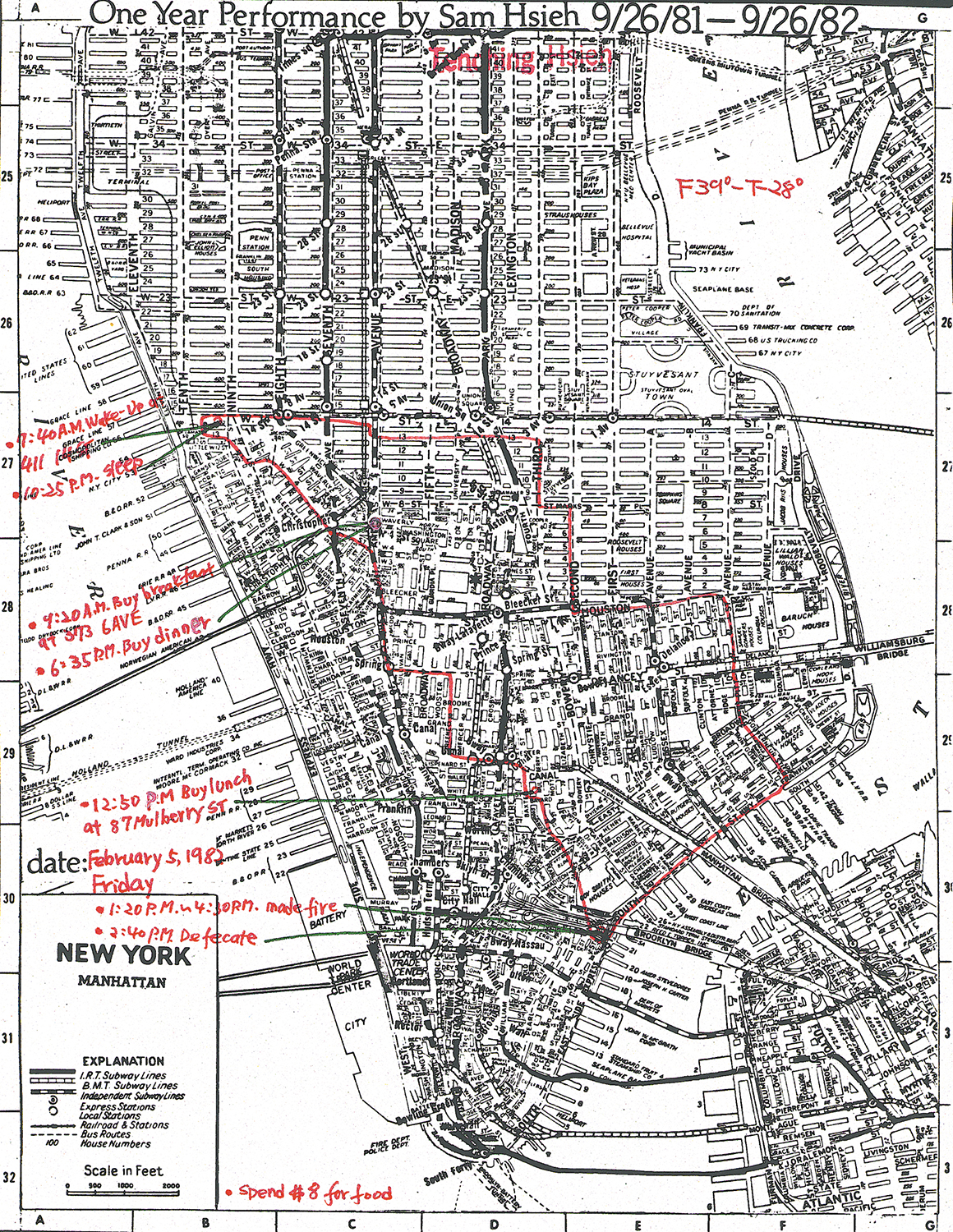

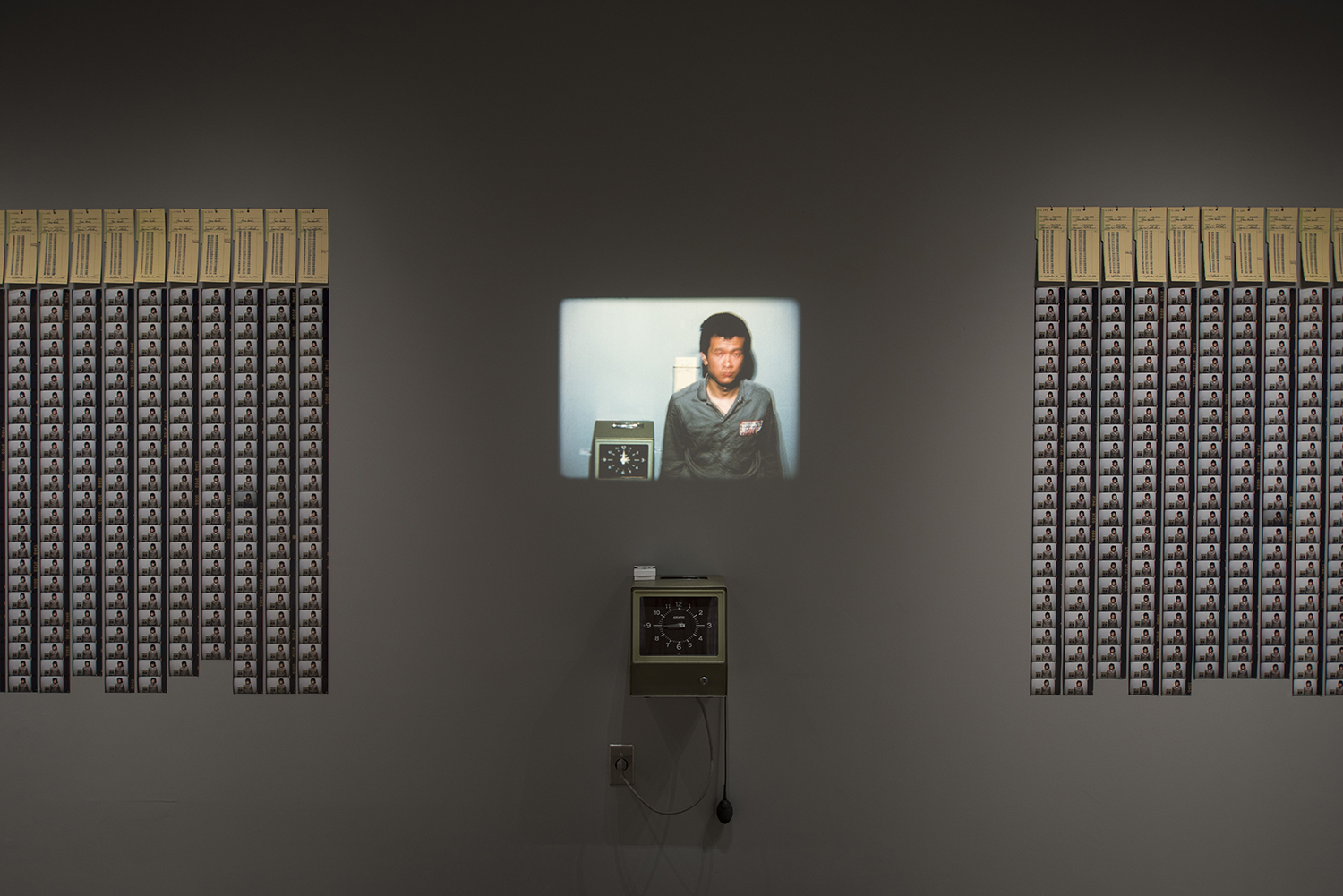

Tehching Hsieh has been many things in life—a high-school dropout, an abstract painter, a merchant-marine sailor, an illegal immigrant to the United States, a construction worker—but he’s best known for the series of “One Year Performances” he launched in 1978 in New York. The first action in the series was to live in a cage, in silence, for one year. This was followed by an entire year, beginning in April 11, 1980, when he tried to punch a time card every hour on the hour—missing only 133 times, largely due to sleep, out of 8,760 occasions. The documentation of the project, including the time cards and the film stills he took of himself each time he stamped the card, marked the passing of time in dramatic fashion. No less extreme was the year starting from September 26, 1981, that Hsieh spent outdoors, not entering a building, subway, or even a tent—except for a few hours when he was arrested by the police.

After that, Hsieh also went underground, not showing his work for more than a decade. He is currently representing Taiwan at the 57th Venice Biennale, with the presentation of Time Clock Piece and Outdoor Piece from the “One Year Performances,” and other early works from the 1970s and ’80s, curated by Adrian Heathfield and organized by the Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts. During the opening week of the Biennale in May, I sat down with Hsieh to discuss his presentation, “Doing Time,” his ideas about “art time” and “life time,” the inspiration he takes from the existential worldviews of Franz Kafka, Albert Camus and Snoopy, as well as how he feels about finally representing Taiwan on the international stage.

Part 1 of this interview can be read here.

So you had figured out your philosophy even before you started the “One Year Performances”?

My work is like Snoopy’s. [Here Hsieh showed me a Peanuts comic strip, a drawing of his own based loosely on one that he remembers. The first three cells are the same, showing Snoopy lying on the roof of his doghouse. Then in fourth cell, Snoopy has switched position. “Life is changed,” Snoopy says.] My performance work is about different perspectives on thinking about life: “Life is passing time” and “life is free thinking.”

I’m no philosopher, and I’m not good at using words, so art was a good way for me to express myself. But in the ’70s and ’80s I was influenced by Dostoyevsky, Frank Kafta, Albert Camus—especially The Myth of Sisyphus. You read most of the influential books at that age. Later in life, you are already a developed person and it just becomes an exercise in thinking. At 24, I got into it. I transformed my own character. I had digested it.

In another interview [in Venice], they asked me how I would pass time today. I never ask myself how to pass the day. I’m just passing time. But I know I did pass yesterday, and I have confidence that I will pass today, and I hope that I can pass tomorrow. That’s all I can answer. I’m not “doing art”; I’m just “doing life.” I’m just consuming time until I die. I don’t believe in the afterlife, so I’m not trying to create a heightened spiritual message about Zen or the Buddha, nor about how to pass time.

When you started the first “One Year Performance,” what did people think about this idea?

In the beginning, I had varied responses from people, because they didn’t know me. After that, Cage Piece (1978–79) became the cornerstone. All my works after that comes from the same idea of a “life sentence,” and that “life is passing time.” They thought it was crazy, of course. And how is that even possible? I didn’t try to say anything, because my life before this time was already very difficult, and for it to be art, you have to make an emphasis, to make it even more extreme. To me, I already had a foundation about life and I had a philosophy about what I believe. I’m stubborn, so I know my reality is not good if I just do a lifetime of “wasting time.” I’d rather choose to do “art time.” Even if I didn’t produce anything, my work is more like I did nothing but I was working hard at wasting time. Even when I lived in a cage, I could laugh on the inside. Even with difficulties, I smiled inside because I know it’s a big joke—but it’s also serious.

These experiences, the “One Year Performances,” must have also been very painful.

They were. Because making these works became a psychological matter. But I didn’t want people thinking that my works were about endurance, or about the pain of existence. If you want to make joy, you have to put in a lot of work, and exchange that for a little bit. If you have joy every day, then you want more every day. It’s like a drug—like cocaine—but how high can you go? Eventually, you will kill yourself. To me, even to get freedom, that takes a lot of work. First there’s betrayal, punishment, suffering—and then freedom. You have to pass through that process—that’s the way I understand human history.

In ancient Greece, they had these myths, and the gods lived in heaven [on Mount Olympus]. But in my work, I’m more like Sisyphus. That means I have to deal with the punishment, and I have to move the cornerstone. So I can be more like a slave, or a worker—that’s my role.

When you were doing these performances, did you feel that what you were doing was different than regular life?

To myself, I don’t make any differences. I can have my free thinking, but in my own body. I cannot use somebody else’s body; I have to use my body. I didn’t live with an empty mind like Buddha’s. I was always thinking—about who was going to give me my next meal, or about art. My art is about survival. It’s just passing time, day by day until I finish. I know how many days have passed and how many days I have to go. I can still control myself and have free thinking.

It’s like Charlie Chaplin—he played many different roles; or like Franz Kafka, who wrote the short story A Hunger Artist (1922). I also play a role, but my performance is in real time. I’m just natural; nobody knows I’m doing this. One day, visitors came to see Cage Piece in my studio. They don’t know where the art was, so they asked me, but I couldn’t answer. [Hsieh took a vow of silence during that piece.] I didn’t say that I’m the art, but I was doing the piece, the performance.

Were you afraid to do these projects before you started?

Afraid? No. I was about 70 percent confident before I started. I always tested the piece. If I could not do it for one week, or if there’s something missing, then I knew I probably couldn’t complete it. Like for Cage Piece, something could have happened—like a fire [Hsieh had sealed himself in the room]. I was lucky I didn’t have this situation.

I did get arrested during Outdoor Piece (1981–82), but they didn’t send me back to Taiwan. I don’t know why they didn’t send me to the immigration department.

After you completed Outdoor Piece, for example, did that change your relationship to other people and the city?

Yes, like a prisoner who comes out of jail and goes back into society, and finds that it is very difficult to adjust, I had the most difficult month of my life when I came out of Cage Piece. I begged to live in a cage in the bedroom. I came back slowly, with great difficulty. In the Outdoor Piece, the irony was that I was in the heart of the city but also in a different world, because homeless people live in another world. In Brooklyn, in my neighborhood, people would say they were going on vacation—but I knew that kind of vacation was actually a sort of jail.

When I finished a piece, there was a kind of depression, because you had to come back. If you could not come back, that meant you were lost. Returning to the accepted norm meant restarting your life again.

Why did you stop the “One Year Performances” when you did?

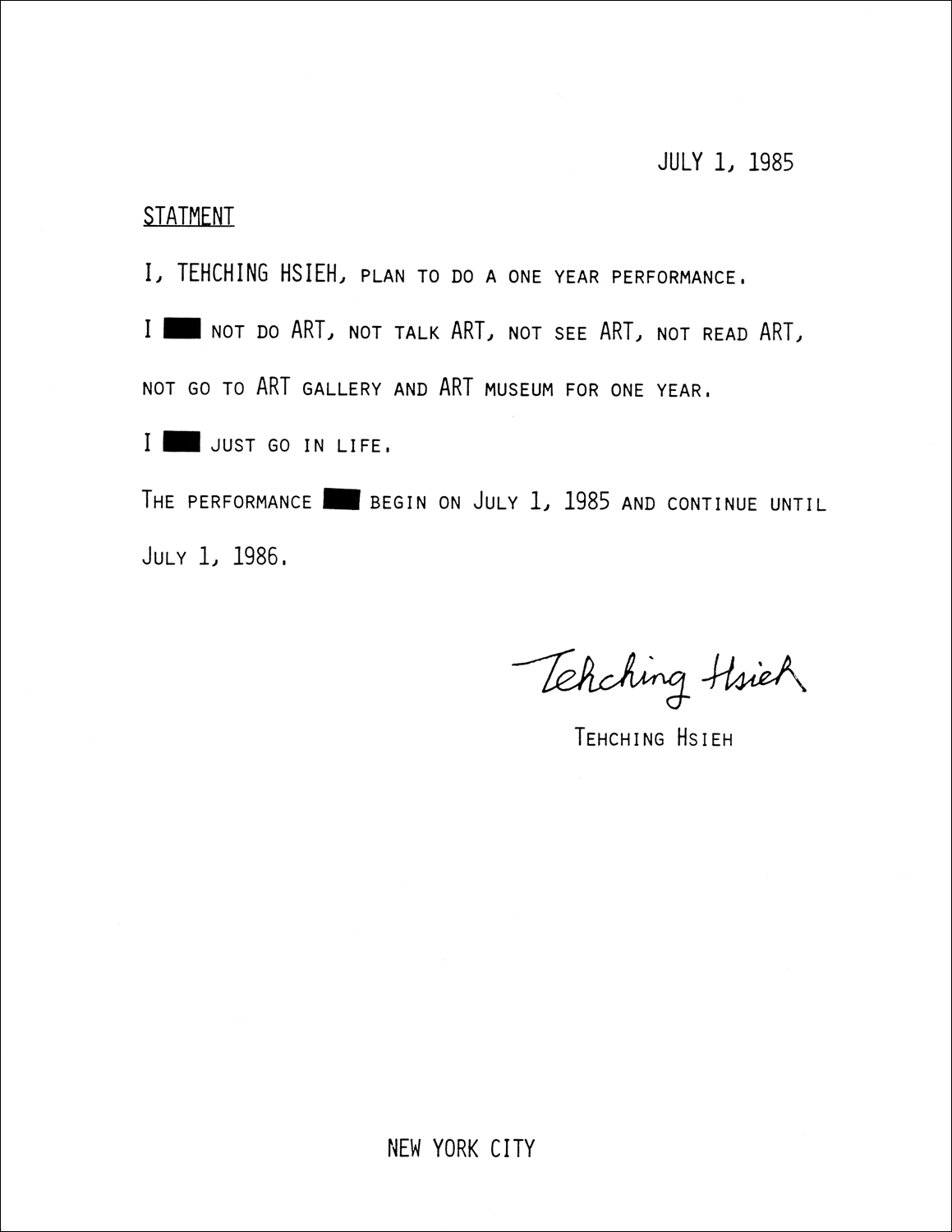

As I mentioned, each of my artworks is call “art time,” and between them is what I call “life time.” After I did four pieces, I knew that I didn’t want to do “art time” for longer than one year in one go. People were already asking me, “What is your next one-year performance?” I didn’t know myself what was next. I wasn’t thinking so creatively. Some friends said why not go to the moon for one year—but I’m not lucky enough to be an astronaut. I just had no ideas after Rope Piece (1983–84). But if you have no ideas, time does not stop. I had a deadline coming. No art, but my life changed. Like Snoopy.

For me it’s the same: The sun will come up in the east and set in the west. You go up and you go down. Then I went underground for 13 years, until I reached the end of the century—that was my deadline. Thirteen years, more than a decade—which meant in New York that you no longer exist. But then I came back in 2009. The book I made with Adrian [Heathfield] in 2009, the MoMA and Guggenheim Museum shows in January [ 2009 ]. It was like winning the lottery. “Life is a like a gift falling from heaven.” [Hsieh laughed ironically.] That’s just a joke.

How did you feel about representing Taiwan at the Venice Biennale?

I have never showed my work in Taiwan before. Like I said, Venice is a tourist center, and this Taiwan Pavilion [in the Palazzo delle Prigioni] is a prison. It’s part of the Biennale, but also outside of it. It’s like when I was homeless, I lived on Fifth Avenue in New York, but of course I was still outside. My work is similar—on the outside, but present in the center.

HG Masters is ArtAsiaPacific’s editor-at-large.

“Tehching Hsieh: Doing Time,” the Taiwan Pavilion, is on view at the Palazzo delle Prigioni, near Piazza San Marco, during the 57th Venice Biennale, until November 26, 2017.

To read more articles by ArtAsiaPacific, visit our Digital Library.