People

Li Hei Di on “700 Nights of Winter”

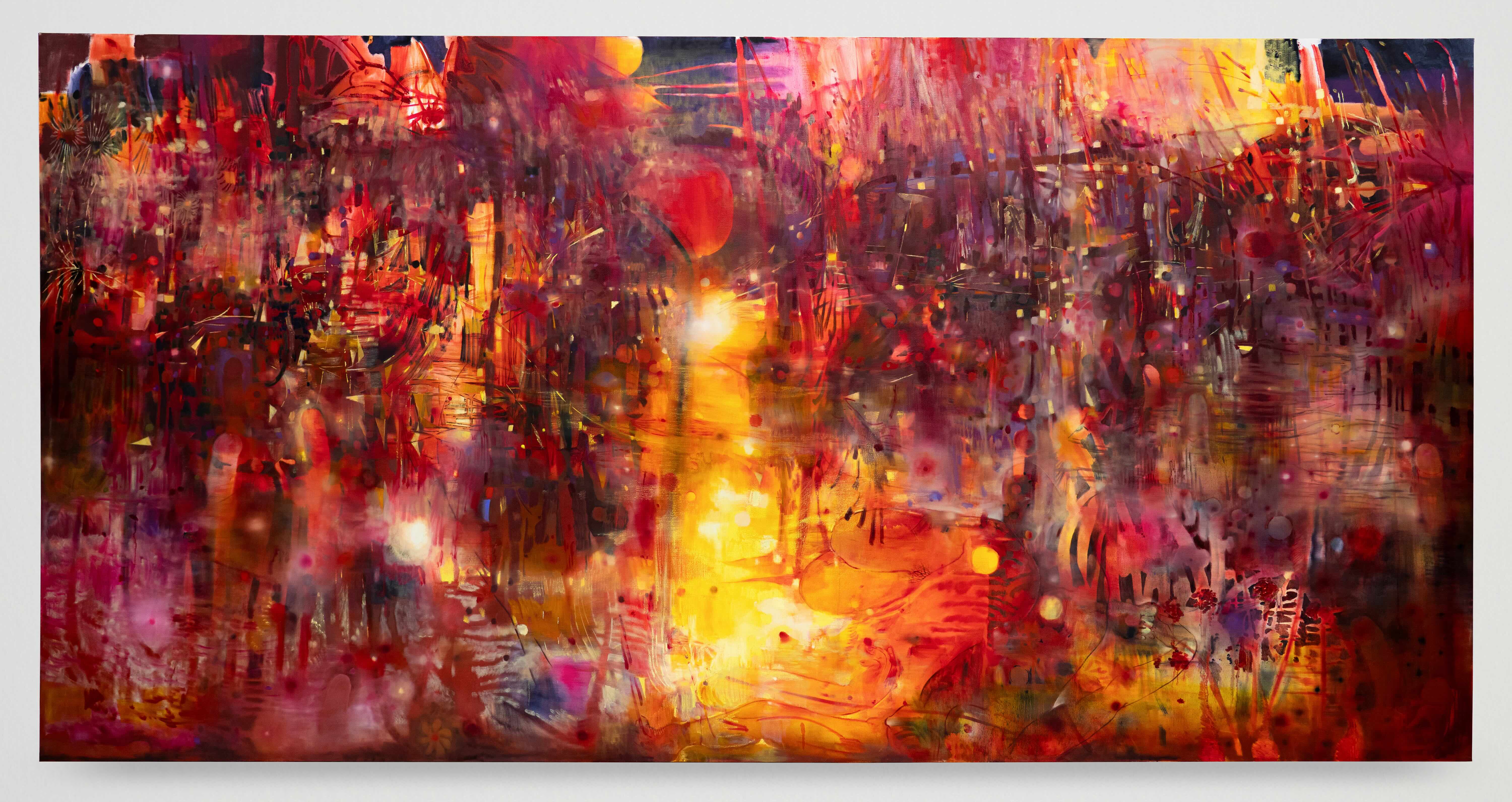

“Pharmacopornographic” hallucinations—borrowing writer Paul B. Preciado’s term—is one way of thinking about Li Hei Di’s paintings, which are rendered in washes of colors, disguising furtive bodies beneath layers of abstraction. Born in 1997 in Shenyang and now based in London after receiving an MA in painting from the Royal College of Art, Li will have a solo exhibition at Pond Society, Shanghai, in 2024. Ahead of the artist’s first solo exhibition in the UK at London’s Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, ArtAsiaPacific asked about their recent paintings.

What does the exhibition title “700 Nights of Winter” represent or reflect about your new suite of paintings? Is there a particular work that feels central to this exhibition?

I came up with the title “700 Nights of Winter” while working nocturnally in the studio. Winter in London felt endless because I could never catch the sun. I lived through what Byung-Chul Han terms “the inferno of the same”—my environment consisted of different shades of indigo with shimmering, artificially orange lights; my sight had become surreal, and daily life felt like strong lights hitting me while sitting in a pitch-black movie theater—these elements played into the paintings. The flesh of the other was a savior on these long, cold winter nights. The work In Folds of Dark Warm Women Flesh (2024) depicts an orgy amid the night, with shades of the morning cool.

Do you think of larger paintings as being immersive? And does scale impact your process or approach to a canvas?

Yes, the bigger paintings are meant to occupy your horizon. For example, when I close my eyes and face the ceiling light, I see a large red “painting-like” vision and flickering light spots swimming under my eyelids. The red inside my eyelids devours me like a bee lost in a virgin water lily, slipping from the stamens and falling into poisonous ponds. I portray this sensation on a large-scale canvas and intend the viewer to feel the same.

What is emotional and intellectual in your painting practice, or your approach to painting?

My paintings are made intuitively, so the emotional and the intellectual are inseparable. It’s like being a vessel in which everything I consume is marinated and let out as emotion. These emotions are then reassembled into daydreams and fantasies on my canvases.

Do you think of the spaces in your paintings as fantasies or recollections, as a hybrid of those and other elements—or as entirely speculative? And would you want viewers to see them as a projection of your own subjectivity, or as a space that exists outside of you and them alike?

The spaces in my paintings lie between memories and fantasies that emerge from genuine emotions. Many people pursue creative acts to be understood and paint to express feelings that are hard to pin down. I’m trying to build a space for these unspoken thoughts and desires and to seek a tacit agreement with others. It’s like a secret little dungeon between me and the viewers, where all thoughts, kind or morbid, are freed from societal judgments.

Who were some key figures inspiring this recent work and what did you draw from them?

Byung-Chul Han’s work has influenced me tremendously in the past year. His book The Agony of Eros (2012) has been my bible. His idea of the “politics of eros” in today's “burnout society” and looking for love within the “inferno of the same” played a huge part in the creation of these works.

Regarding painters and other visual practitioners, who are important or influential figures for you?

Miriam Cahn’s work is an indispensable source of inspiration to me. The haunting yet effortless nature of her work is what I long to harness.

Winter also makes me yearn for getting closer to nature. The colors and the elements of this body of work are very much influenced by Sexual Encounters of the Floral Kind (1984)—I’ve watched quite a few nature documentaries. For example, for Breast to Breast I Face Your Hunger (2024), I thought about how ribbon weed reproduces in water—tiny male flowers drift up from the bottom of the water to the surface where the female lies in wait.

How do you feel your practice has evolved in recent years? Is there a direction you are heading toward or areas you want to explore?

My work has changed a lot recently, and so have I since entering adulthood. They have become more layered and fragmented as I’m becoming more obsessed with every detail on the canvas. My work has also become less abstract and more provocative as I am becoming more self-assured. It’s hard to predict where my psychology is taking me through my painting practice, but I have a dream that one day I can bravely paint every stroke with purpose, creating effortless and confident images.

Li Hei Di’s exhibition “700 Nights of Winter” is on view at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery in London from March 15 to April 20, 2024.