People

Hu Yinping’s Economy of Knitted Relations

Full text also available in Chinese.

Beijing-based artist Hu Yinping often starts her artistic projects by looking at the socioeconomic conditions of those around her and in her environment. In 2015, for her project Xiao Fang (2015– ), she established a company and hired a friend to use the eponymous pseudonym to purchase knitwear from her mother and women in her hometown, which Hu then uses as artworks for exhibitions. Initially, she asked the women to knit green hats, which were frowned upon by the local community but welcomed in festive Irish parades. Through this ongoing project, she has tried to stimulate the imagination and creativity of her mother’s generation, which had been exhausted by the rote work of the garment industry.

Hu has exhibited her works both in China and internationally. October 2023 was a busy month. For her show “Xiaofang Universe Bank” at the MixC Nanjing, she transformed the mall’s exhibition space into an interstellar bank and a financial hub with a currency exchange between countries represented by various commodities, all sharing the whimsical internal structure of wool.

At the Paris Internationale art fair (October 17–22), Magician Space presented “Hu Xiaofang – Snow White Dove,” bringing together hand-knit bikinis by her mother’s network. It was a colorful collection of swimwear fueled by the imagination of faraway seashores. From October 28 to December 16, Hu’s work traveled to Mexico City for “A Story of a Merchant” at Kurimanzutto gallery. The speculative group exhibition, curated by X Zhu-Nowell and Chao Jiaxing, wove together personal narratives, travelogues, historical artifacts, and architectural interventions. Currently Hu is participating in a group exhibition titled “Smart Order” at Beijing’s 69 Art Campus in a project that sheds light on the absurdity of the modern-day workplace.

Early in 2023 during Art Basel Hong Kong, ArtAsiaPacific spoke with her about her reflections on her latest works, the Xiao Fang project, and “Torture Instruments” series.

Two of your latest works, Crime of decoration, one with overdressing and Crime of prince, a prince of a clan (both 2022), were exhibited at Magician Space’s booth during Art Basel Hong Kong in March 2023. Both featured golden torture instruments that restrict the bodies of the prince and queen who each wear elaborate patterns on the head. Where did these patterns come from? What inspired you to create these works?

Crime of decoration and Crime of prince (both 2022) are two from the “Torture Instruments” section in my latest project The Moon Rises From Within . . . (2022). This work is a kind of metabolism when facing the outside world. In real life there are so many unanswered questions about genetics, history, and civilization. For example, a vegetable seller may not want to sell vegetables for a living, but the family, the culture that he was born into, and the knowledge structure has already determined that he can only sell vegetables. If vegetables were to be a scarce commodity, his skills would become more valuable. But the human genes and human society have determined this and it cannot be changed. There are so many disappointments in reality. Just as the body needs metabolism, so does the consciousness.

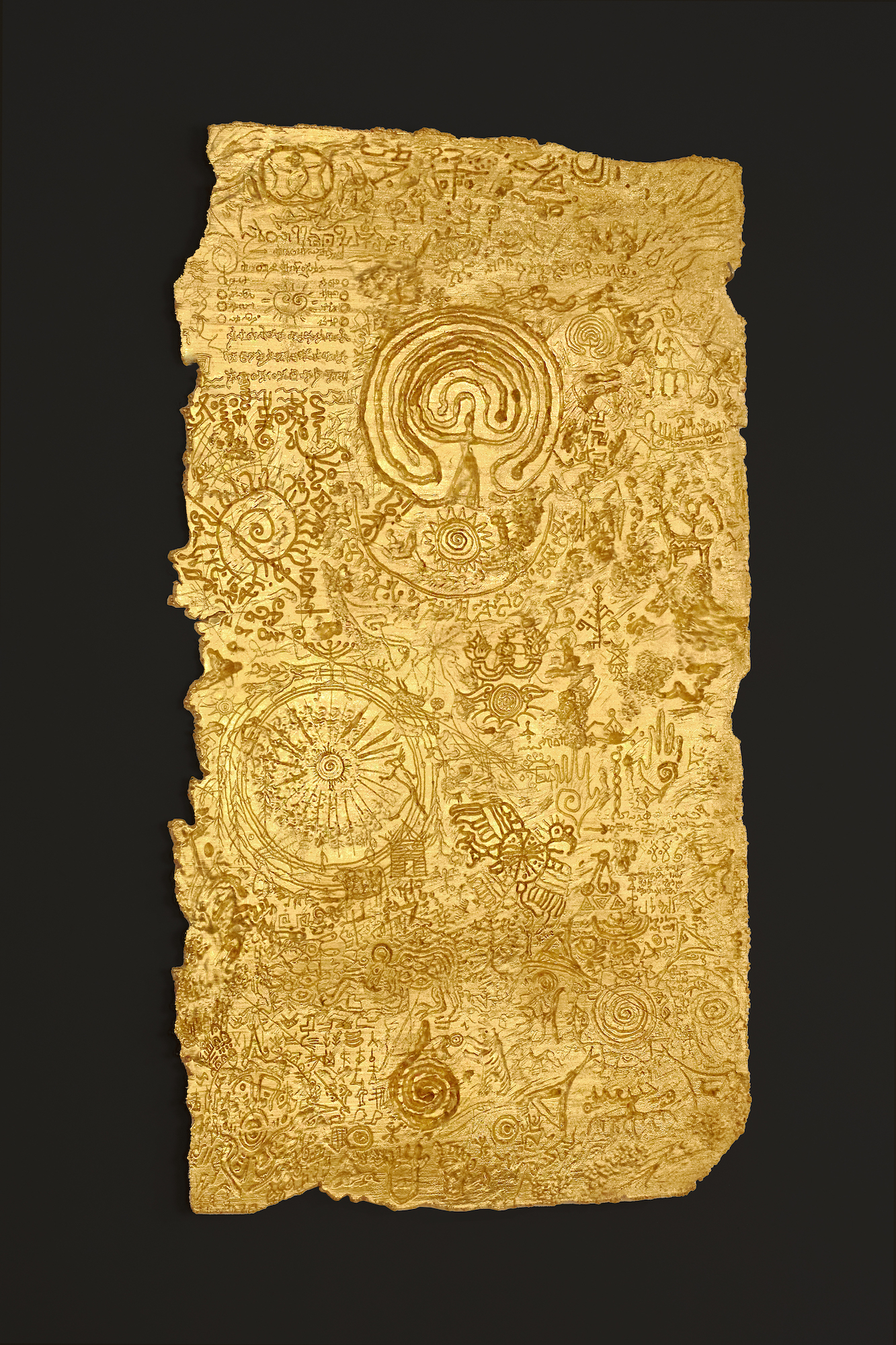

The body and consciousness pose the greatest limits to humankind. Made of gold, the torture instruments restrict the wearers’ bodies in different ways, depending on the crime committed. The patterns on the instruments are deposits of consciousness from various civilizations, intricate and heavy as the skin. They derive from various historical, religious, and astronomical sources, including petroglyphs, Persian miniatures, and nebulae patterns. But it doesn’t matter what the source is, or which religion it belongs to. The essence of all religions is the same for me—I just use them.

Comprising 24-karat gold, bronze, and resin, these two works are very different from the sculptures you made in the past under the pseudonym “Qiao Xiaohuan.” Are there any technical difficulties in making these multilayered instruments and intricate patterns from gold?

The “Torture Instruments” series suggests a way of looking at reality from another perspective, where gold is no longer synonymous with power and wealth, but crime and punishment. I did draw very complicated patterns, often to the point that the software on my computer crashed. The thick patterns are usually made up of eight to ten layers of gold leaf stacked on top of each other. My focus was not on the technique of making specific objects, but on the relationship between each artwork and myself. I want to bring more thinking into the work, especially all sorts of crazy ideas.

For your ongoing project Xiao Fang (2015– ), what are the factors you consider before exhibiting it?

Making handicrafts takes a long time. I also have to spend time sorting out my ideas on the concept of the artwork. If I take the exhibition to a new place, I have to consider how Xiao Fang relates to that place. For example, If Xiao Fang were to be displayed in Hong Kong, I would face the problem that there are no small towns in Hong Kong, and that people have a completely different understanding of what it means to be a farmer. I have to think it through clearly before giving the women in my town appropriate theme for the knitwear—one that is not only relevant to me but also to the women there. I don’t want to rush. I hope that those women can have their own pace and the same for myself.

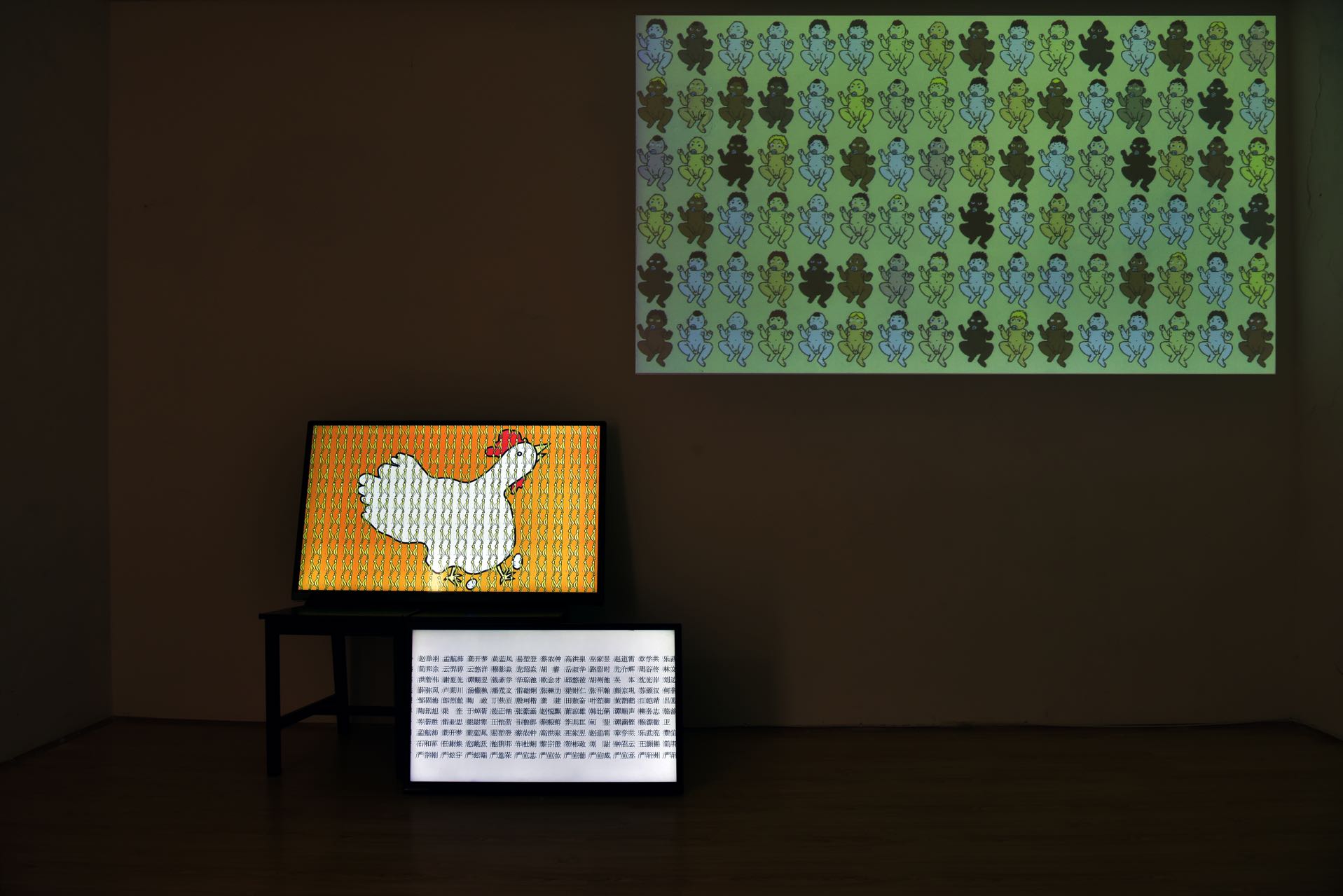

In We're all in the Worksuit (2022), a recent chapter in the Xiao Fang project, you asked these women to come up with their own quotes and stitch the texts onto the “Worksuit.” What are some of the most unexpected quotes to you?

It’s interesting to see how they reflect on their own professions and on those of the people around them. Maybe they haven’t thought about it in this way before. For example, a woman was assigned to stitch texts on the work outfit of a courier. Maybe one of her family members or friends was a courier, but she usually just complained a little about this profession and then continued her daily life. It was not easy for her to describe this profession in her own words and make comments about it.

So we had to chat with them a lot and guide them on how to think about it. But some of them refused to think and sent a message to our studio’s manager: “Zhao, I really don’t know what to say.” We told her to stitch this message down. She then understood that everything she wanted to say could be sewn onto the workwear.

I was touched by a blue workwear outfit covered with the word “tired” in big and small letters. When they thought of the profession, the first word that came to their minds was “tired” and they didn’t want to say anything else.

.jpeg)

How do you manage the finances of your Xiao Fang project? Do you plan to continue this model of art-making elsewhere?

It’s certain that we lose money overall, but in the past year or two, we’ve stayed level, which I am happy about. People have come to our shop to buy things after the exhibition. An artist manages a brand differently from an entrepreneur, and there is a huge difference between a market economy and a planned economy. I used to think that if my mother could knit that way, all the women could knit like that as well and I would buy their hats. It turned out that I might have to support 30 mothers—which in reality I couldn’t afford, since many women were not as responsible as my mother.

There are both good and bad sides to human nature. You might buy 3,000 hats and end up with 1,000 either too big or too small for people to wear. Then you find out that you need the market to help regulate them. Also, if you couldn’t sell all 3,000 hats, you would understand how the market works and what pressure there is in warehouse operations. So I had to change from a “planned economy” to a “market economy” model. I am running this artwork within a company, so there needs to be a management system, not just a shell of a company. Otherwise it would have closed down long ago.

Whether or not to continue this kind of art production elsewhere depends on the market. If there is a market for it, we will set up another branch.

You said that there are both good and bad sides to human nature. How does business reveal this?

When a company is free from regulation, there is bound to be laziness. For example, after I told the knitters that we were a foreign company, some women thought that whatever they created would be bought, since no one would know who knitted what items when the goods arrived in France. This is laziness and greed, but also part of human nature.

We don't supervise the workers directly. We let them govern themselves and choose a literate and competent representative to talk with us.

Some of your works deal with certain social stereotypes. For example, in your 2016 exhibition “Thank You,” you created a strategic plan for parents to choose their infant’s gender based on their preferences, and for Identity (2012– ), you changed your appearance to mimic a woman whom you initially disliked. Is this approach resistance, sarcasm, or reconciliation?

I think it acknowledges that such things exist. Although you can reach reconciliation on an intellectual level, it is still there. I need to answer it myself. I think artworks are the best means to reconcile with myself. I’m thinking about not only “Thank You” and Identity, but also The Moon Rises From Within . . . (2023), which I’m working on now. Because you have no other way. You can’t just cry like a baby or roar to let it out. Many things are rooted in me and can only be addressed through my work.

It is the benefit of being an artist, and it’s the same for being a musician, filmmaker or other creative jobs. You can have an authentic relationship with your artwork and strong connection with yourself.

Is art-making also a kind of healing for you?

Not, it is so simple as healing. It’s almost excretion, a kind of cleansing and metabolism. Only through the metabolism of consciousness can your whole consciousness be unblocked, regrow, and refresh. We need both physical metabolism and consciousness metabolism. It’s just that in this industry, we tend to present our metabolism of consciousness in the work itself.

Qin Wang was an editorial intern in 2022–23 at ArtAsiaPacific.

Chinese editing and translation by Lin Ai, one of our current editorial interns.