People

Geopoetic Curating: Interview with Patrick Flores

Nations, regions, and axes—these geopolitical concepts often direct us toward understanding contemporary art within confining contexts. But it’s high time to explore ideas beyond these boundaries. Coming from Filipino curator Patrick Flores, one of the leading voices of Southeast Asia’s contemporary art scene, this is an assertion to be believed. “It’s not just about disrupting,” he clarifies. “It’s more about expanding.”

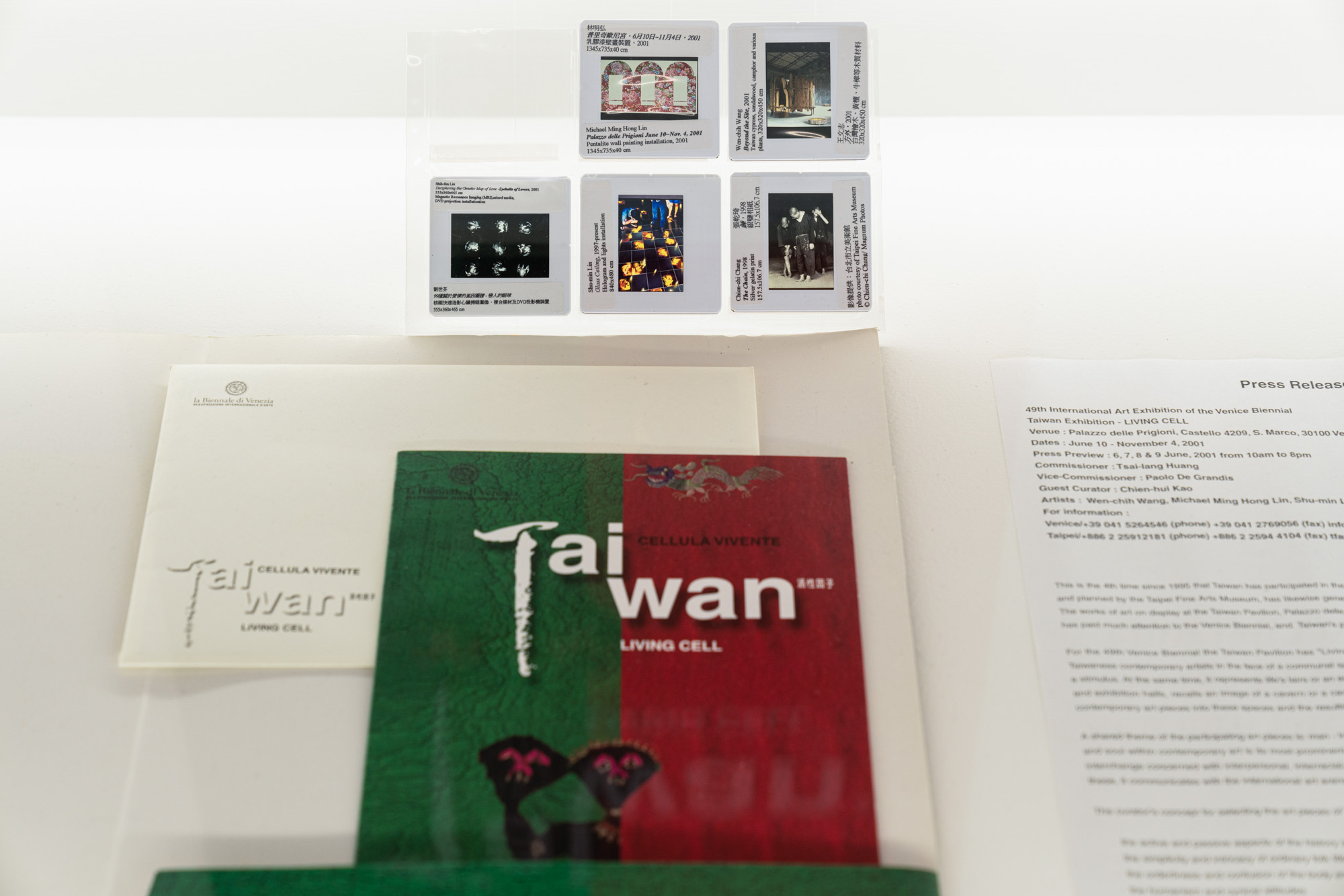

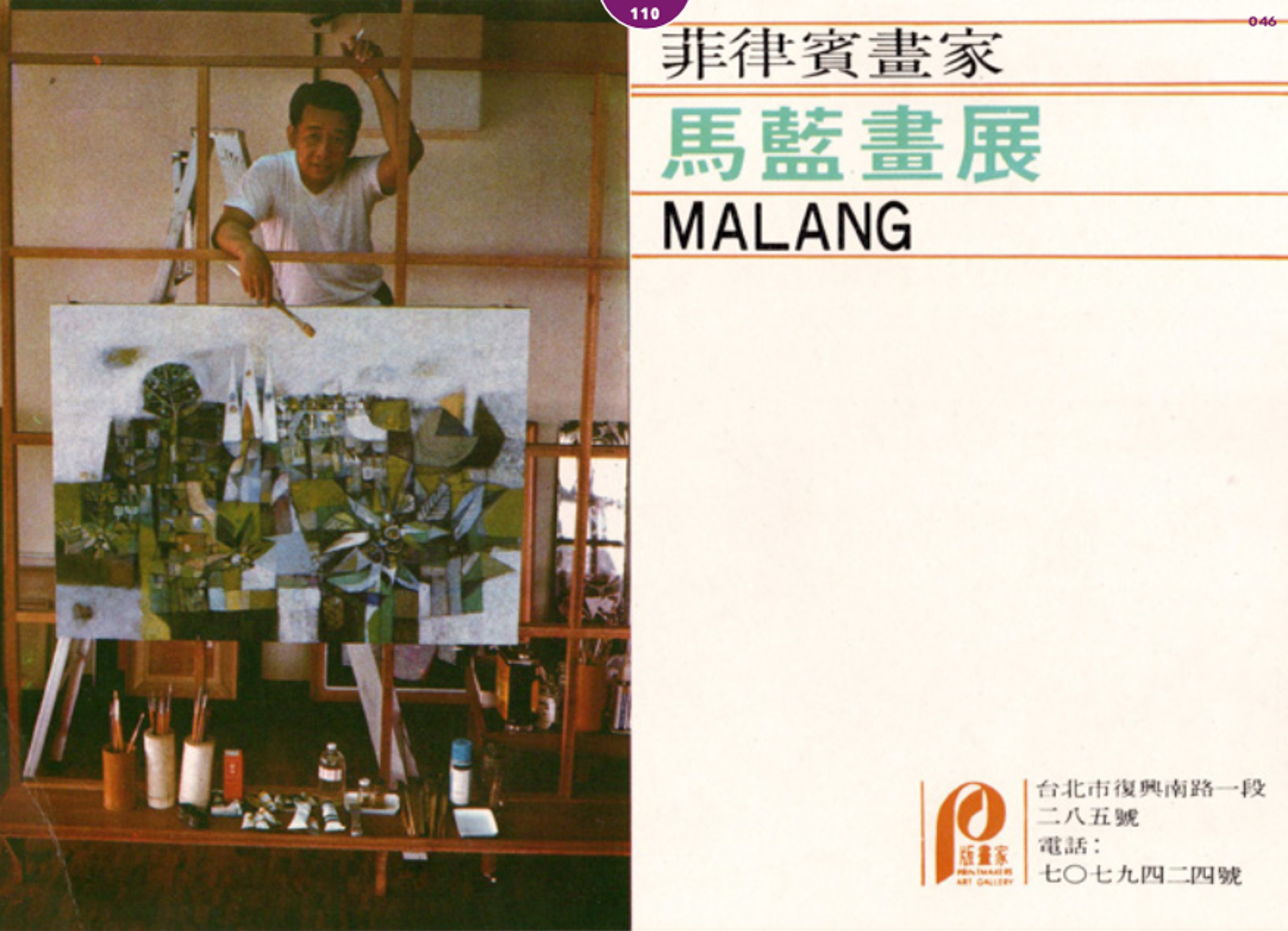

Flores began his attempts to develop perspectives on Southeast Asian art with two cross-regional group shows at the nonprofit Osage Hong Kong. The first, “South by Southeast,” co-curated with Anca Verona Mihulet in 2015, focused on the links between Southeast Europe and Southeast Asia, and in 2019, “Present Passing,” co-curated with Natasha Becker, looked at the commonalities between the Caribbean and Southeast Asia. Building on these explorations, Flores co-edited the book Meridians of Region: Writing Art History and Curating Contemporary Culture in the Philippines and Taiwan (2021), which reveals the deep cultural ties between the neighbouring countries of the Philippines and Taiwan. Finally, his reflections were consolidated in Taiwan’s collateral exhibition at the 59th Venice Biennale, “Impossible Dreams,” his second curatorial project at the major festival following the Philippine Pavilion in 2015, called “Tie A String Around the World.” AAP sat down with Flores to discuss how he grows and uncovers artistic links through his writing and curated shows.

Can you tell us about your approach to the Taiwan Pavilion at the 2022 Venice Biennale, and how was it different from your curation of the Philippine Pavilion in 2015?

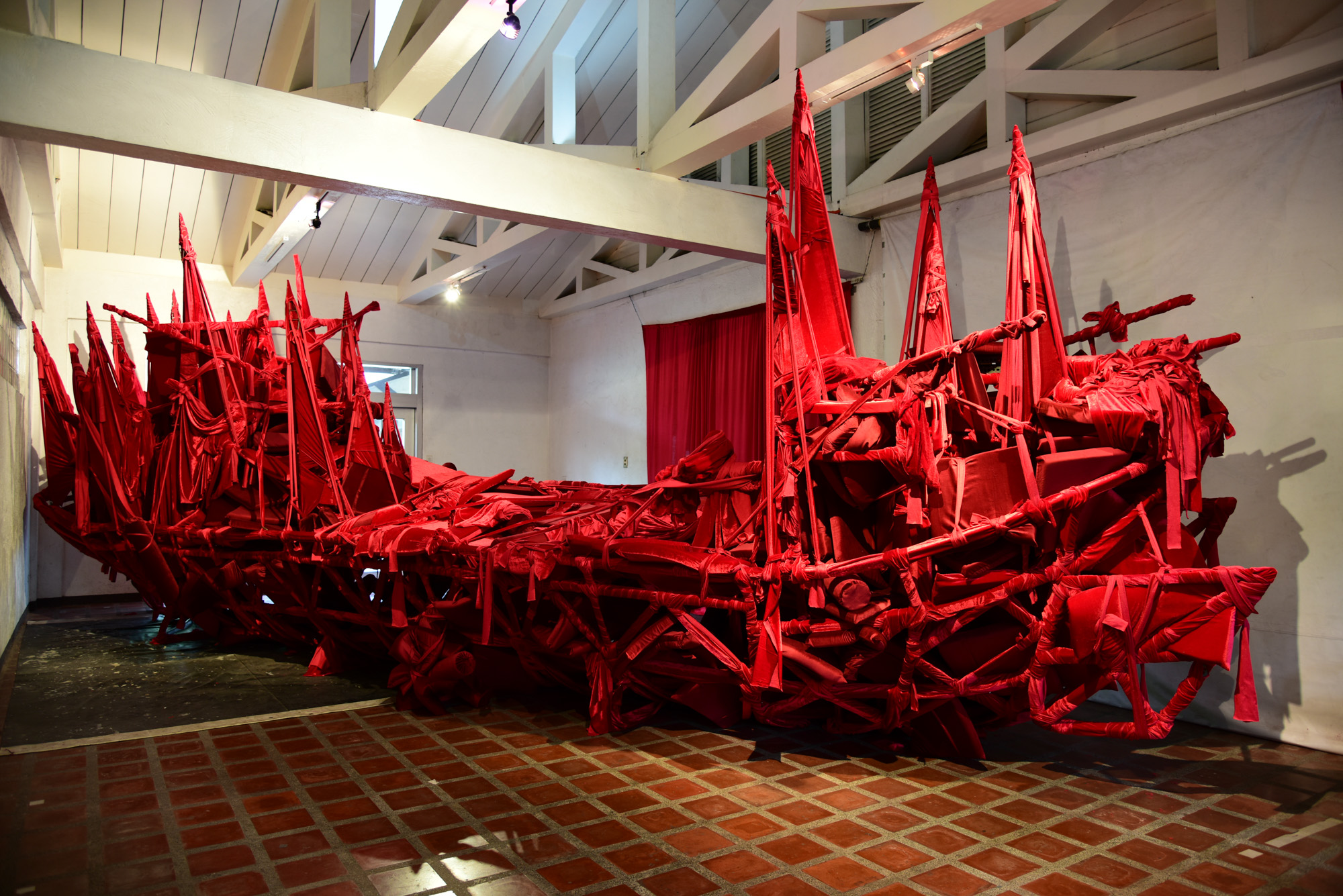

I come from a different background because I’m not Taiwanese. But even with the Philippine pavilion, I tried to complicate the idea of what a national pavilion is. Back then, I tried to think about this idea of the South China Sea and reconfigure what the region is, in the context of a nation-state. Taiwan is not considered a nation-state, although there have been claims. I’m interested in the tension and instability in this idea of the national. It’s very stimulating for me to think about this fluidity.

That’s how I approached this almost default expectation to understand national-pavilion systems, and what it means in 2022. For me, the ocean is the connector. The Philippines is closer to Taiwan than Southeast Asia, so there are exchanges culturally and geographically. Also, I look at Austronesia as a possible way to move beyond the confinements of art from the north-south axis. Austronesia might offer a different constellation to Taiwan and the Philippines, and an alternative way to connect them, resulting in a different art history, if it’s still art history.

Lately, I have been talking about these ideas in a book with Taiwanese art historian Chiang Po-shin, called Meridians of Region, where I explore the culture and traditional art of the Philippines and Taiwan to broaden the links between the two.

In Meridians of Region, you reconsider the art histories of both the Philippines and Taiwan using the unconventional metaphor of acupuncture. Is curating close to healing for you?

In acupuncture, the meridian is a pathway, a trajectory, not an unyielding locus or a fixed point. Acupuncture is a method that excites these pathways and the energy traveling through. This idea opens up inspirations for how curatorial work can index both context and material. Such a mode prevents the temptation to render one or the other an instrument to signify a fully formed object of desire. The curatorial pulse, therefore, is akin to a prick of the needle on the skin of a context (whether society or culture, history or the body, and so on) so that it can be enlivened and redeemed from stagnation. It is indirect but symptomatic and therefore ultimately systemic. The acupuncture trope also speaks to an ethical intelligence that rests on patience and the capacity to let the process of healing play out in a long duration. Curatorial impact need not be immediate, but it can be lasting.

As you said, you consider the ocean a connector. Do you think curators today need to create these ties to move beyond artificial geopolitical limits or do these ties just need to be rediscovered by research?

If curators were attentive enough to the ecology, they would sense the waters around seemingly formidable territories. The oceanic as a trope and the oceanographic as a procedure may lead us to think through the global via migrancy, travel, resettlement, statelessness, piracy, exile, and so on.

You have written of the residues of the “colonial” and the “modern” in contemporary art, and the “representational imperative” within the nationalistic projects of the “colonial-modern.” Do you find that these concepts have evolved in the last ten years?

Yes, the needle of the discourse has moved mainly because of the reconsiderations of what we mean by “modern” or “modernity.” What has lagged is the reconsideration of the “colonial” even as there seems to be an overinvestment in the “decolonial,” in which the colonial is hardly theorized and the separation as signalled by the prefix “de” is governed by the avant-garde obsession. With regard to the “representational imperative,” I think there are efforts to move away from recognition as the privileged politics of presence, something that has been encouraged by the “national” and its identity-effects.

For the show “South by Southeast” at Osage Hong Kong, and its modified iteration in Guangzhou, you used the theme Southeast in what you define as “geopoetic” terms. This idea of geopoetics as opposed to geopolitics is fascinating. How does this concept drive your curatorial practice?

I wanted to retain the political history of geopolitics as it is instructive and emblematic of national consolidation under the aegis of the region and the international order. That said, I wanted in the same vein to dissolve the attendant politics through a poetic mediation of the place so that the politics do not ideologically overdetermine artistic form, which surely is political but need not be reduced to a geopolitical instrument. It is the “place,” broadly conceived, that generates the conditions of the form, which in turn predisposes the said place to produce creatively.

The show “Present Passing” likened the art from Southeast Asia with that of the Caribbean. How do you, in practical terms, initiate a show like this?

I look for places in the world that express a Southeasterness geographically, at least initially. The coordinates can shift, of course. This is why there are many ways to look at the southeast, which is originally relational. I begin with the coordinate, not the point, again like the meridian. I take it from there. I also look for someone with whom I can collaborate. The iterations of South by Southeast have emerged from curatorial collaborations.

You have spoken of the necessary ethics in the process of remapping the world through curation and writing. What are the tenets of this ethics?

Part of the ethics is the reconsideration of the worldly as not necessarily colonial or modern. Here lies the opportunity to re-world via the curatorial act and re-write the worldliness in a different tenor. The cartographic, therefore, becomes restitutive rather than an instrument of extraction, capture, and alienation.