People

Gardens of Earthly Delights: Interview with Ming Fay

.jpg)

.jpg)

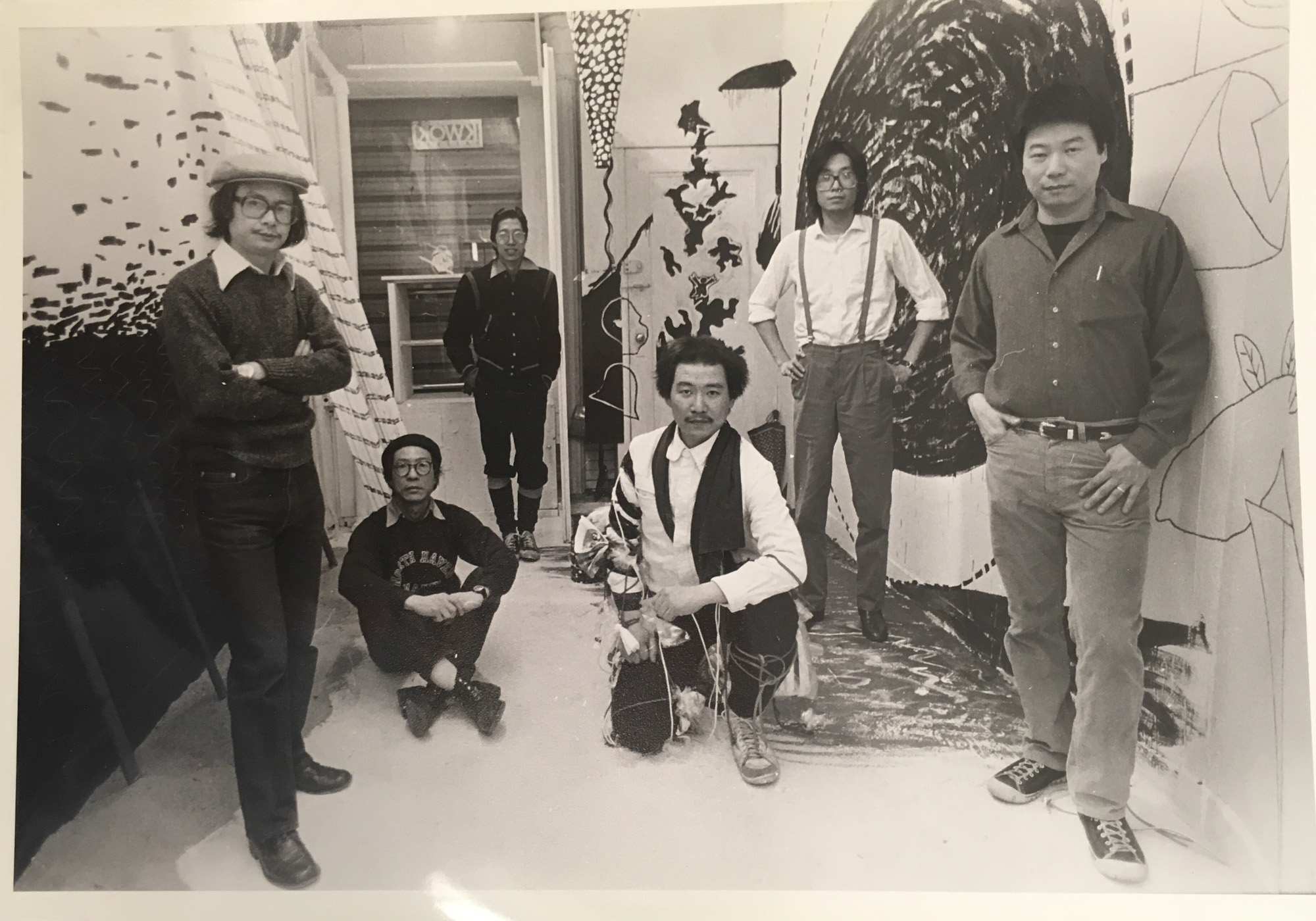

Born in 1943 in Shanghai and raised in Hong Kong, Ming Fay is a New York-based sculptor celebrated for his large-scale, life-like sculptural renditions of plants, fruits, trees, and other organic forms. One of the co-founders of the Epoxy Art Group, which brought together ten Chinese American artists working in experimental media from 1982 to 1992, Fay has exhibited internationally and has been commissioned by numerous cities to create large-scale public sculptures. After coming to study design in the United States in the early 1960s, he discovered that his passion was for sculpture. He received a BFA from the Kansas City Art Institute in 1967 and an MFA from the University of California, Santa Barbara in 1970. He has taught at several universities in both Hong Kong and the US over the last five decades and was a professor of sculpture at William Paterson University in New Jersey. On the occasion of his current exhibition at Alisan Fine Arts in Hong Kong and a newly released monograph, ArtAsiaPacific caught up with the artist to ask him how it feels to look at his career retrospectively and what keeps him inspired today.

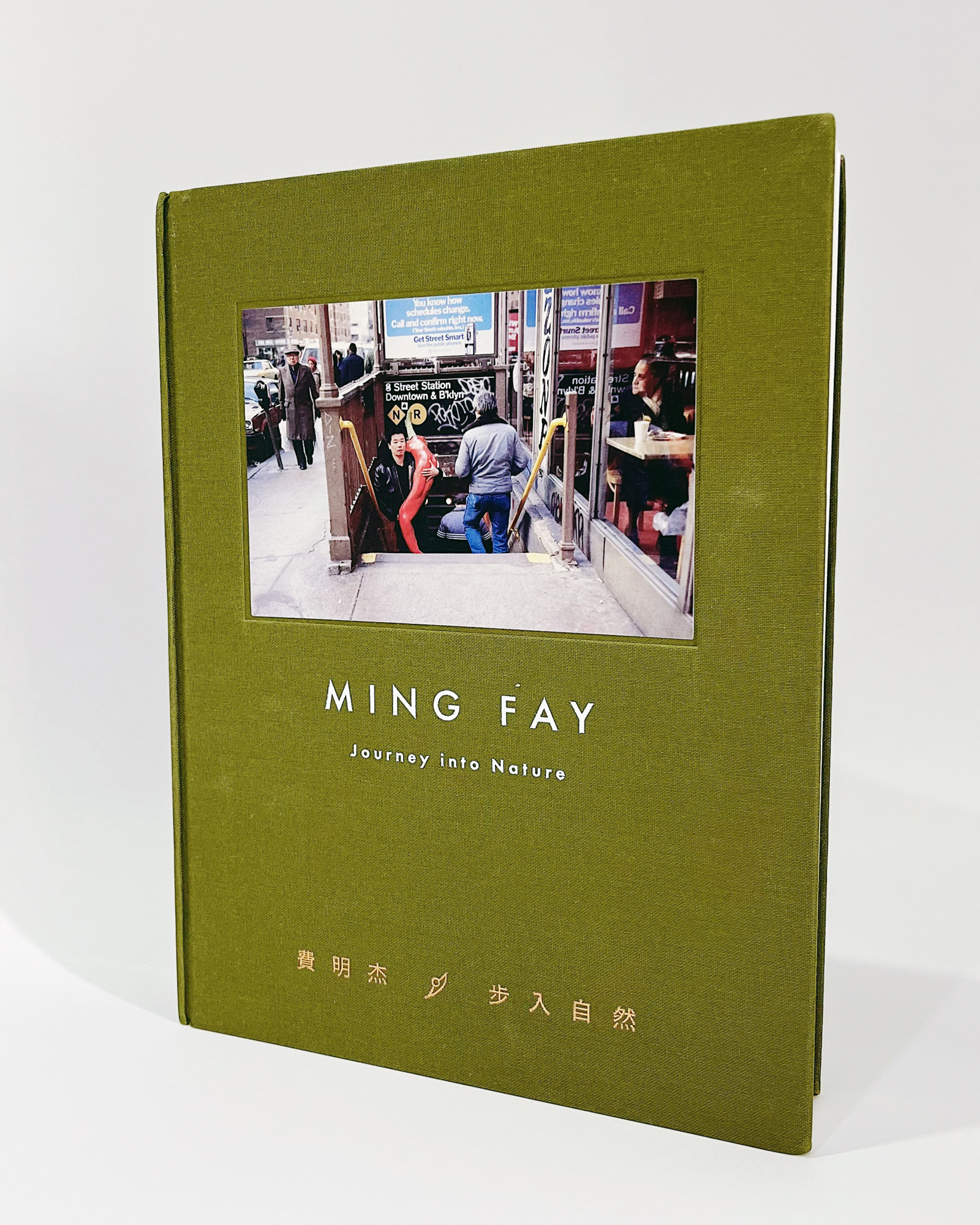

Your 423-page artist monograph Journey into Nature (2022) has just been published by Alisan Fine Arts in Hong Kong. How did you feel when you viewed all the works and projects throughout your artistic career?

It is a surreal and deeply emotional experience to see my life’s work compiled in a book. Every page brings up many memories. My first interaction with the book was surprising—a gift I received at my apartment in downtown Manhattan, shipped overnight after its first printing in Taiwan. It was nostalgic and moving; I spent hours looking through it that night. I love the way it turned out and feel grateful to my son and the team for capturing my artistic vision and 50-plus year practice in this huge project.

.jpg)

Your son Parker was largely responsible for undertaking the production of the book. One of the essays in the book mentioned that when you created your first wishbone sculpture, you made a wish to have a son and that wish came true. What is your first memory of introducing your artwork to your son, and did you ever imagine that he would be so closely involved in your art?

It’s hard to pinpoint when Parker first interacted with my work; he grew up alongside and around it. My sculptural garden populated our living space and served as the background of his playground from when he learned to walk and climb. My artistic practice grew alongside him as well.

I never thought Parker would be so involved with my work as I have always just focused on making art. I’m thankful he has worked on many studio projects, especially the two current shows at Alisan Fine Arts in Hong Kong and “Oneness: Nature and Connectivity in Chinese Art” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. I see his involvement in the studio as a point of connection between us.

Going back to your own childhood, growing up visiting the palatial surroundings of Tiger Balm Gardens in Hong Kong must have made a deep imprint in your imagination. Can you recall that visual experience from the perspective of a young boy? How did it shape your vision of the world, and ultimately your own distinct artistic vocabulary?

I first visited Tiger Balm Garden as a child in the early 1950s after moving to Hong Kong with my family. It was an unforgettable landscape that I can still vividly remember—seven acres of surreal sculpture depicting animals, figures, pagodas, and other scenes derived from Chinese mythological stories scattered across a scenic peak near Causeway Bay.

It remains a garden that I remember to this day, one of many that perhaps influenced my work in some way; not in its quality of craftsmanship but more so for its symbolism and the experience of walking through it for the first time as a boy. Another favorite garden, though it is part of folklore, is the mythological Celestial Peach Garden in Journey to the West, which ripens once every 9,000 years and grants whoever consumes its fruit immortality.

The garden has remained a throughline of my entire artistic career. I see the concept of a garden as a symbol of abundance, paradise, and the location for the ultimate, desirable state of being. As humans we are consumed with desires and long for a lost utopia. The garden that I have created is a mindset where I cultivate an imagine place for mystical forms to exist in a sculptural landscape.

The book has wonderful historical documentation about the Epoxy Art Group. As a founder of Epoxy in New York, can you remind us of what it felt like to be an overseas Chinese artist working in the city in the 1970s and ’80s, well before the globalized art world emerged at the turn of the millennium? What were the desires, frustrations, and triumphs of the group?

It was lonely to be a Chinese sculptor working in New York City at that time. It was rare to meet a Chinese artist, rarer to meet a Chinese sculptor. Epoxy started as a group of us gathering for dinner parties to discuss all sorts of things. The original group was from Hong Kong but it grew to have members from Taiwan, mainland China, and Canada at different times. We were already gathering socially and thought why not collaborate as artists? The basic desire was to create something we wouldn’t normally attempt as individual artists; collectively pushing the boundaries of our usual subject matter, materials, etc. That was the most important thing to us. But then the question was what do we make?

The name “Epoxy” was chosen for its material properties—it is composed of two parts that must be mixed to form one permanent bond. This was symbolic of each of our cross-cultural backgrounds, and our projects that bonded Eastern and Western cultures, mythology, and history.

For each project, we would have many meetings to brainstorm what we should make. People would throw out ideas and finally something would stick that we could build off of and it was trial and error from there. For the exhibition “36 Tactics,” at first we stayed up many nights making masks and photographing ourselves in different poses. When that didn’t work, someone came up with the idea to xerox images from newspapers and microfilm and overlay the image with epoxy glue and text from Sun Tzu’s Art of War. We did this in a few trips to the New York Public Library on 42nd Street to research images from microfilm and newspapers, and the piece grew from there. We didn’t have the internet back then. We were always operating on extremely low funds.

Your student Kwok Mang Ho, also known as Frog King, lived in New York for a few years and joined the Epoxy Art Group, but later returned to Hong Kong. Was leaving the US ever something you contemplated?

I’ve contemplated returning to Hong Kong, but it has never happened for various reasons. New York is my home and has been for the past 50 years. I am happy to be here. I am just as much a downtown New York City artist as a Chinese artist. My artwork reflects the cross of these energies, the tensions, intersections, and convergences of the two.

.jpg)

Many curators and critics interpret the gardens that you have created throughout your career as a continuation of the tradition of Chinese literati landscapes. There are also symbolic references to Chinese culture, in the form of legends and myths. However, the references are presented in a subtle and playful way, through the oversized scale of the fruit, the saturated colors and the sometimes surrealistic forms. Was this a strategic device to help non-Chinese audiences in the US understand the richness of Chinese literature and culture? Did any of your audiences express their desire to learn more about the Chinese literati gardens?

My artistic project does not explicitly try to teach Western audiences about Chinese culture, though a subset of my American audience has felt inspired by my art to learn more. Instead, I see my art as a reflection of my hybrid, cross-cultural background. There are explicitly Chinese interpretations of my work and explicitly Western interpretations; both are correct because both elements are there.

My Chinese audience, for example, might immediately understand my symbolic references to traditional Chinese mythology, tradition, and history. They may have grown up gifting and receiving oranges on Chinese New Year and may intuitively discern the nature of my gigantic oranges bringing “extra luck.” My Western audience might look at my work and see saturated color, or think of themselves in a sort of “Alice in Wonderland” environment.

There are also aspects of my work that are beyond culture and entirely universal. Every child has at some point picked up and excitedly examined found treasures of seeds, shells, or nuts. Things loomed larger when we were young. By rendering these forms human-size and making natural objects a viewer usually walks over, something big they must walk around, I create a confrontation with nature. I force the seeds and nuts we tend to ignore into focus so my adult audience can recapture that spirit of childhood wonder at nature's beauty, symmetry, and flawless design.

The cover of your latest monograph features you carrying a larger-than-life chili pepper as you emerge from a New York City subway station. What was the public’s reaction to you carrying these steroidal “fresh” fruits and vegetables on public transportation? Was this a performance or just the practical act of moving your sculptures from studio to gallery?

We captured that photograph in the mid-1980s to promote an upcoming show at Broadway Windows in downtown Manhattan. People were staring at me on the streets, but it is difficult to shock a New Yorker—people here have seen everything! Carrying a giant pepper over my shoulder while walking down Broadway was just another unusual sight.

Do you see your work as individual pieces or the sum of a whole alternate world—a garden of earthly delights? Does the influence of Hieronymous Bosch play a role in your creations?

I create individual pieces—realistic sculptures of real or imagined natural phenomena. Each piece I create is a celebration of nature. In every work, I bow to the natural world. These pieces come together to create something new—a garden or jungle that I have been growing in my studio for 50-plus years. A surreal, immersive, experiential element emerges. My work is now an experience one must walk through. The experiences that my landscapes evoke change depending on the unique internal landscape of the viewer who walks through them. Though I appreciate the landscape works of Hieronymous Bosch, his work isn’t an influence of mine.

.jpg)

What is your ideal institution for exhibiting all your sculptures and installations?

I don’t have an ideal institution in mind. Every space I have worked with brings its unique properties and challenges. For example, when exhibiting at Grounds for Sculpture in Hamilton, New Jersey, I showed my work in a 10,000-square-foot warehouse traversed by pipes and support beams. We used these industrial elements to hang my natural forms from, creating a canopy hanging overhead while my other sculptural works were displayed on the wall beneath. At Montalvo Arts Center in California, my Monkey Pots (2008) hung from the trees on the grounds. My Garden of Qian (1998), or Garden of “Money,” was shown at the former Whitney Museum of American Art’s space, right in the center of midtown Manhattan, one of New York City’s bustling business districts. The connection is there. My work is always aware of its surroundings, the environment a viewer must leave to enter the gallery.

Maybe my ideal exhibition space is in New York City, as this city has made my work what it is. I began collecting, studying, and creating natural forms because I spent so much time in New York. When living in a completely urban and artificial environment, the distance from nature becomes very apparent. Nature is not a significant part of life for most New Yorkers. I am interested in their experience as they interact with my artwork.

The title of your monograph is Journey into Nature. For a garden artist like yourself, what were the attractions of the city? Were you ever tempted to have a studio in the woods or on a farm?

I was attracted to New York because of the world-class museums, pioneering galleries and the dream of making it here as an artist. New York also has one of the biggest Chinatowns in the world, which was important for me for the sense of culture and community early on. Though I recreate natural forms, I am a city boy at heart. I explore and appreciate nature with my sculptures, but I have never lived for a long time in a natural environment. I haven’t seriously considered a studio in the woods or on a farm. I am happy to have landed in New York.

Ming Fay’s “Journey Into Nature” is on view at Alisan Fine Arts, Hong Kong, through December 24, 2022.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.