People

The Essential Works of Chiharu Shiota

Osaka-born, Berlin-based artist Chiharu Shiota is most known for her room-sized, textile-based installations comprising thousands of fine threads, which form intricate webs, claustrophobic clusters, or even tunnels. Growing up in a family that runs a hectic, small factory in Osaka, Shiota decided at the age of 12 to become an artist and explore spirituality, asking difficult questions regarding her own identity and existence. She began with painting and eventually enrolled in the undergraduate program at the department of painting at the Kyoto Seika University. During her travel to Australia as an exchange student, she started exploring installations and performances. She later traveled to Berlin to study under performance artist Marina Abramović, who challenged her students to go on a one-week fasting to test the limitation of their bodies.

Informed by Abramović’s influence as a mentor in her formative years, Shiota’s works deal with both body and territory, weaving together personal narratives and universal experiences about memory, identity, and belonging. Her works have been exhibited within Japan and Germany, as well as in other international museums such as the Smithsonian, Washington DC; the Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels; the New Museum of Jakarta; and the SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah. The artist also represented Japan at the 56th Venice Biennale in 2015. Her largest solo “The Soul Trembles” first opened at Tokyo’s Mori Art Museum in 2019, before traveling to Taipei and Shanghai in 2021. In light of the show’s Brisbane edition at Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art, ArtAsiaPacific examined seven of Chiharu Shiota’s most essential works throughout her 25 years of artistic practice.

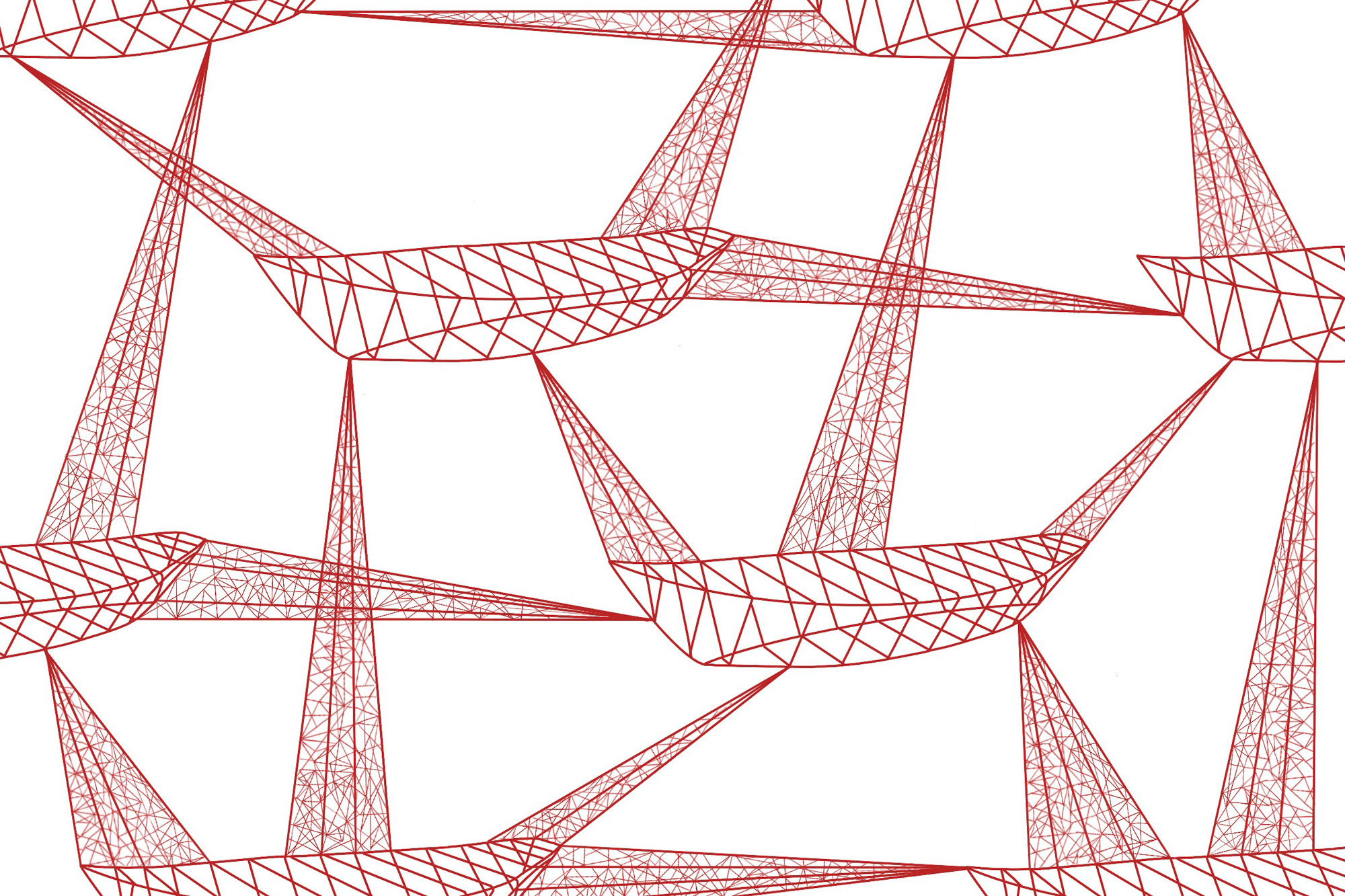

Shiota initially studied painting at the Kyoto Seika University, but she struggled with the medium, as she failed to establish a spiritual connection with it. This frustration led her to creating installations, including From DNA to DNA, which was “a three-dimensional picture with strings.” The red string, one of the most significant elements in Shiota’s practice, first appeared in this mixed-media performance-installation at her graduation exhibition at the Kyoto Seika University. She lay on scattered, small pillows which resembled red blood cells on the floor, with her body tangled by red strings connected to the bundle on the ceiling similar to an umbilical cord. “It was an artwork where I became a part of the DNA’s history. I became a piece of art. I was born from the artwork,” explained Shiota in an interview with Louisiana Channel.

When Shiota was studying painting, she found it difficult and stressful to produce self-portraits. The inability to draw herself bothered her enough that painting haunted her dreams, in which she was immobile and surrounded by oil paint. Her nightmare inspired her first performance Becoming Painting. She was wrapped in a piece of white cloth and covered in red enamel paint, which caused serious burns on her skin. After the performance, the red paint stained her skin and hair for months. The performance was cathartic for Shiota, as she explained later in an interview, “It felt liberating creating art with my body. It was a liberation from art as a skillful practice.”

A recurring motif in Shiota’s works is the dress. First appearing in the 1999 installation After That, a white dress is covered in dirt and showered by a water fountain but irreversible to its original clean state. She later renamed the work as Memory of Skin and expanded it into a large-scale installation for the Yokohama Triennale in 2001, which featured five 13-meter-long muddy dresses draped from the ceiling, with a continuous shower of water from above. Here, dresses are considered as “second skin” for Shiota and the impossibility of cleaning them suggests how clothings, even when they are not worn by humans, carry memories with them that cannot be erased. Body, intimacy, memory—these are the subjects that later Shiota often returns to.

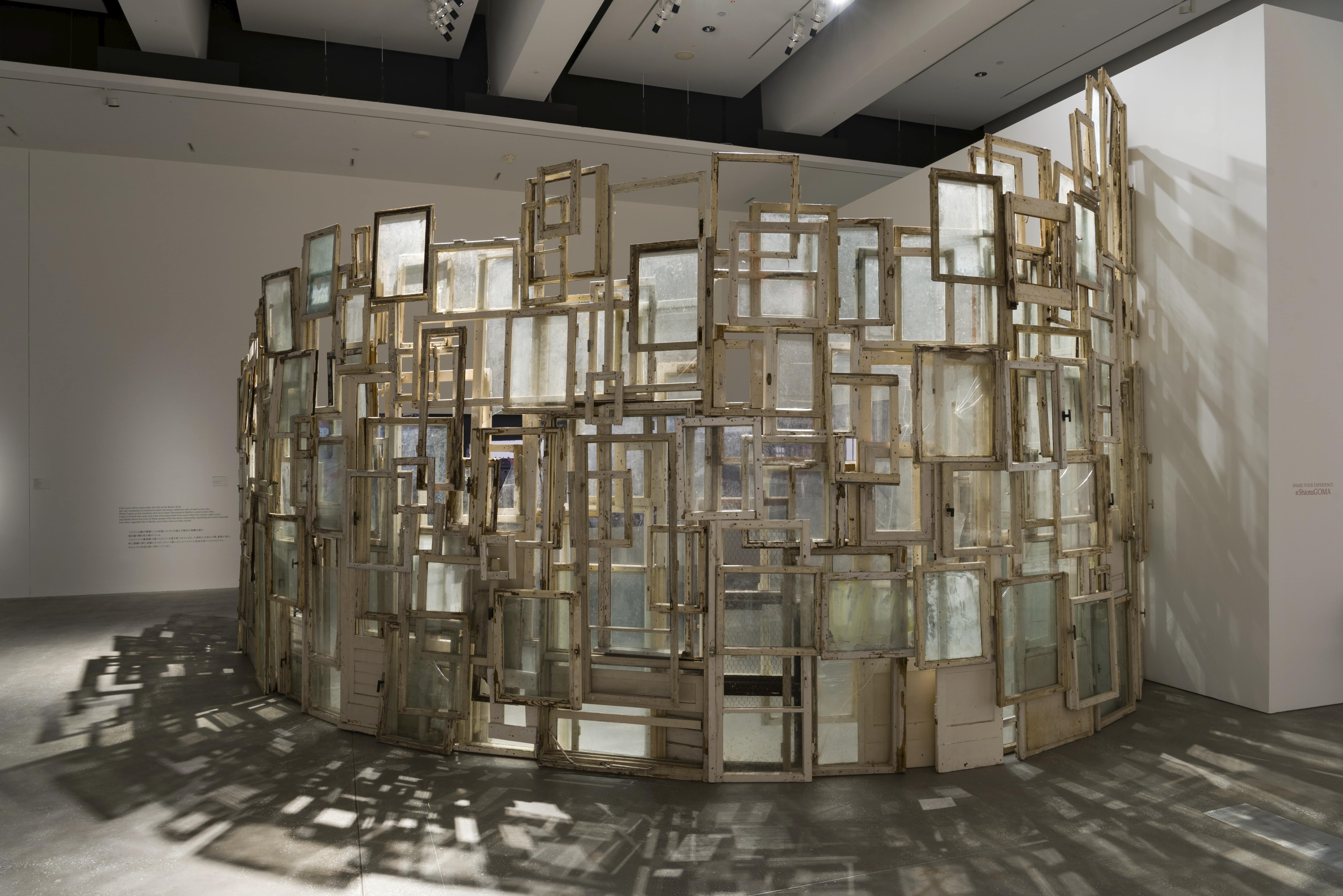

In 1996, Shiota arrived in Berlin, which had experienced a period of political turmoil after the fall of the Berlin Wall and was slowly rebuilding itself to be an important node in the global economic network. For Shiota, Berlin was a “town in motion” that was “constantly renewing itself.” She gathered hundreds of derelict windows from old houses standing where East Berlin was, wondering “how East Berliners felt about the West Berliner’s way of life.” Using these windows, she mounted, compiled, and formed a large-scale structure in the shape of a house. She likened the windows to her skin, dividing the inside from the outside. As an immigrant, Shiota felt that her identity existed somewhere in between Germany and Japan. Against the backdrop of mass displacement and immigration, the fragile, transparent structure in House of Windows demonstrates the vulnerability of peripatetic modern nomads who have to make a home wherever they find themselves.

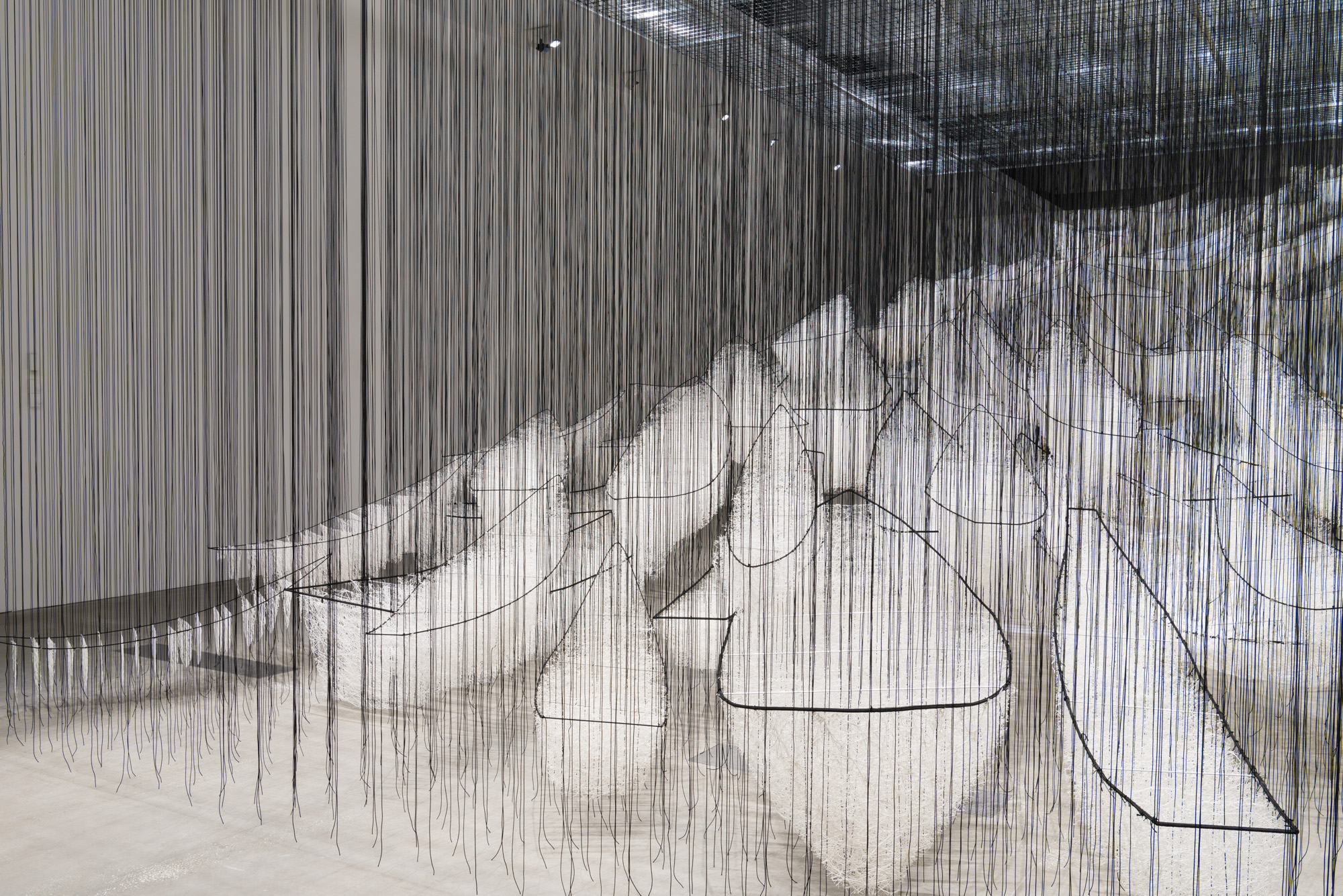

Growing up, Shiota had struggled to understand her tough, authoritarian father, who was not supportive of her decision to become an artist. For the last 12 years of her father’s life, he was partially paralyzed due to a severe workplace injury. When Shiota visited him in 2012, he was immobile and struggled to recognize his daughter. Triggered by this reunion, Shiota decided to create a project at the Museum of Art in Kochi, her parents’ hometown. For Letters of Thanks, she collected thank you letters from people of all ages, ranging from toddlers, who had just learned to write, to the elderly. She interweaved 2,400 letters with massive, intricate webs of black wool threads. The arrangement evokes Japanese shimenawa, which are sacred ropes used for ritual purification in the Shinto religion and omikuji, letters of wishes tied to trees. Unfortunately, her father never experienced the installation as he passed away two weeks after the opening. Her grief also led to later installation The Key in the Hand (2015) at the Japan Pavilion, Venice Biennale, for which she collected 50,000 keys from all over the world.

Where Are We Going? (2017/19/22)

Shiota uses red and black threads in most of her work. 2017 marked the first time she used white threads in Where Are We Going? at a department store in Paris. The installation was suspended white threads in the air with 150 metal frames in the shape of a boat—another recurring motif in Shiota’s work that alludes to her nomadic experiences. A reiteration of the work consisting of 65 boats was shown at Mori Art Museum during her solo exhibition in 2019. Although white was initially chosen for marketing purposes, she started using the color in other works such as Butterfly Dream and Beyond Time (both 2018). Shiota explained, “I use red yarn because it resembles blood, the body, and human relationships. White yarn is pure. In Japan, the color is connected to death. It is a blank space, it is timeless.”

In 2017, after 12 years in remission, Shiota’s ovarian cancer had returned, which coincided with her invitation to hold her retrospective “The Soul Trembles.” She described chemotherapy as a “mechanical” procedure that made her feel like a product on a conveyor belt. To Shiota, the excruciatingly painful treatment and the confrontation of death was a “tribulation to create honest works.” Out of My Body presents severed bronze limbs and appendages scattered under hanging swathes of shredded red cowhide. Created apropos of her experience with removing parts of her body for the sake of health, this interpretation of Shiota’s recurring battle with cancer calls to mind the abject and challenges ideas of propriety and cleanliness in the context of the body.