People

Encountering the Same Line Twice: Interview with Hung Fai and Wai Pong-yu

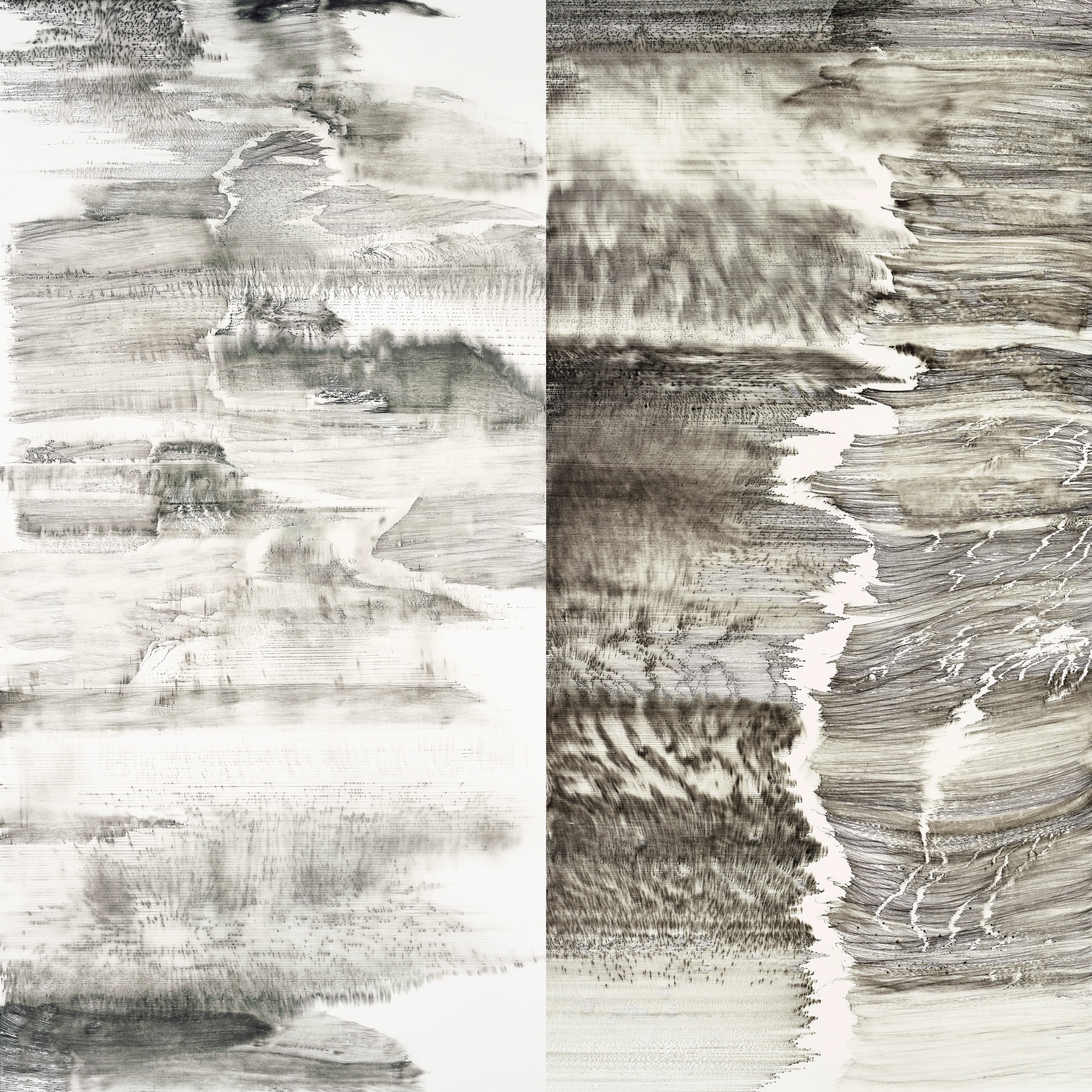

Two men sat shoulder to shoulder on a boat, each holding a pen to draw lines on a paper, beginning from opposite corners. While one drew his lines freely, the other carried a ruler for guidance. The glaring sunlight was harsh and cruel, and the boat drifted in tune with the waves. The ruler was too hot to be held, so the man replaced it with a prism to refract light onto the paper. While a focalized ray served as a guide, his pen no longer leaned onto the ruler, rendering him as free-handed as his counterpart. The second man also struggled: his drawing hand pressed against the paper tensely to not be jolted by the waves. Later, the men decided to take the paper onto a floating platform and draw in harmony with the ocean. This attempt was unsuccessful, as the paper became soaked with seawater and tore, and neither could hold steady enough to draw. Finally, the men returned to the boat, showing off the paper as a result of their artistic process.

Such is the plot of Same Line Twice 23 (2020), a video documentation of the eponymous ink painting by Hong Kong artists Wai Pong-yu and Hung Fai, known for their line-focused paintings. Both artists were born on September 18 (Wai in 1982, Hung in 1988); both attended art school at The Chinese University of Hong Kong; and both have been represented by the same galleries. However, while their lives have many parallels, a divergence emerges in their practices of line drawing. Stemming from his family tradition of Chinese ink painting, Hung creates washed ruler-guided ink lines that rebel against his roots, using new tools, abstraction, and ink-diffusion on folding papers. In contrast, Wai’s free-hand ballpoint-pen ink line drawings are often intuitive and text-based. Using ink without water’s diffusion, Wai explores personal stories, changes in social landscapes, and the cosmos.

%20x%2068.7%20cm%20(left%20upper%20edge),%20pigmented%20ink%20and%20biro%20on%20paper,%202016.jpg)

In 2016, a commission for the artwork of the book The Developing World of Arbitration (2018) saw the collaboration of the artists for the very first time. The project was eventually crystalized as the “Same Line Twice” (SLT) exhibition at Grotto Fine Art in 2017. Later, in 2020, curator Alan Yeung joined the force and helped produce several documentations of more collaborations for the exhibition-title-turned series, resulting in two videos on the process of SLT 19 and SLT 23 (both 2020), among other recordings. At Grotto Fine Art in Hong Kong, ArtAsiaPacific spoke to Hong Kong line-drawing artists Wai Pong-yu and Hung Fai about the meanings and practices behind their collaboration, which has since transformed into the series “Same Line Twice.”

How did this process of collaboration begin?

Hung: We both felt a certain connection that started when this opportunity arose. There are still many fulfilling coincidences, like studying in the same art school, sharing a birth date, and using lines in our works. But when it comes to the expression, we have quite different attitudes and approaches.

Wai: Before we discovered all the coincidences, we were already considering how we could collaborate. When our friend Anselmo Reyes proposed the opportunity, we decided to try it out. The first time we painted together, I used a ballpoint pen while he used an ink pen. We thought it would make for an interesting match. However, we soon realized it wasn’t working out and decided to try again. It was the first collaborative painting, so we needed more confidence. We used the same materials the second time, but the painting still turned out a bit stiff. It was the third time that we worked much better together. We found a rhythm, and as we discovered and engaged with more interesting problems, we realized this will be quite a serious collaboration.

%20x%2096.5%20cm%20(height),%20pigmented%20ink%20on%20paper,%202016.jpg)

Do you always use the same tools to draw?

Hung: When we encounter different problems, we solve them with different sets of rules. These rules can involve creating a new environment, choosing tools, body gestures, and even the direction in which we sit.

Wai: During the process, our communication through line drawing is frequent and often influenced by the materials and mediums themselves, as well as the ways we use them. Even if we use the same ink drawing pen and agree on the same rules, we can develop quite different expressions and interpretations. This diversity fuels progress and can even lead to antagonism.

Hung: Reading, understanding, and responding to each thin thread-like line is challenging. The paper’s moisture can alter the physique of ink lines. Thus, the meaning might appear different from the intended act, which can induce conflict or misunderstanding.

Viewing the collaboration, I can see each of your personalities, which are quite different. How do you handle the process and use your methods?

Hung: I take time to respond to Wai’s action—his strength lies in his dexterous poetic association with imagery and his ability to form new expressions; it feels like a stream of water. So, I take on the role of a submerged rock that can receive his signals and eventually echo them. At one point, I felt that the evolving drawing experience was liberating as we intentionally shaped an ambiguous space. I would describe this transformation as the rock’s outer shell becoming elastic. This flexibility is required to enter this ambiguous space belonging to no one.

Wai: It is fun to provoke Hung and try new ideas together during the process. In SLT 11 (2017), I used a traditional brush to evoke a hierarchical condition that Hung is familiar with from his ink-painter father. To alienate him, I mixed dark blue ink, which, unlike red, doesn’t symbolize power and sacrifice. When the dark blue ink breaks down and fades over the wet paper—suggesting melancholy and ephemerality—it becomes difficult to respond with an unbending ruler. That night, we had to work until morning to catch the last moisture of the damp paper. As the dark sky turned into a hazy blue, Hung tilted his ruler to add the final layers of lines. That added an arched dimension to the drawing, transforming the cold divergence of our lines into a composition of lines sitting accordingly with a shorter distance between our individual components.

%20x%20138%20cm%20(height),%20pigmented%20ink%20and%20brush%20on%20paper,%202017.jpg)

I came across the video SLT 23, and I was captivated not only by the process of documentation, but also by the suggestion of a possible aspect of performativity—like a performance of drawing. Do you consider the video part of the process, like performance art?

Wai: The process is always important, throughout the collaboration. I am fascinated by the new rules, settings, gestures, and improvisations we develop through hours of discussions and preparations. We use new findings and explore their meanings in the following works. SLT 23 originates from a small stream in SLT 4 (2016) and undergoes several transformations to become a conscious being in SLT 10 (2017). In SLT 23. Our curator, Alan Yeung, suggested that we draw in the sea, which made me think that he embodies the human form of the stream’s reincarnation, guiding us back to the home of water, a sea of the mind. The video may be part of a long-duration drawing performance captured by the witness’s lens.

Hung: On moist paper, water can actually capture a sense of direction, body dynamics, and time. These traces could be hints for viewers to imagine the process. When viewers look at the video, they will see the effects of the brutal sun and choppy waves on us.

What were the material conditions like when SLT 23 (2020) was created?

Wai: It was such a beautiful day at sea, but the sun was brutal enough to cast a dark shadow that weighed heavily on me. Most of the time, I could barely open my eyes. The sea appeared calm, but in fact, I struggled with my pen as the boat constantly rocked. Communication through the reading of lines became incredibly challenging. My mind felt enclosed, overwhelmed by all these unrivaled powers. I attempted to anchor my thoughts to a rock on the shore and draw slowly. Ultimately, it felt as though we had only managed to capture a sense of shipwrecked driftwood in the drawing.

Hung: We always set new rules and simulate new conditions for each collaboration. SLT 23 (2020) stands out as the most intense experience. In the natural environment, we had very limited means to withstand its harshness, especially the scorching sun. The dazzling white space of the paper and the heated black ink compelled us to jump into the sea. The improvisations we made during the process surprised us. As we paddled back, the motion of dipping and pulling the paddle felt akin to another form of drawing. The ability to paddle in sync with one another could be a metaphor for human coexistence within nature.

For the 2020 exhibition at Beijing’s InkStudio, the process of making the works was more properly documented than with the older series. How are those works different from those in 2017?

Wai: There appear to be more social elements in the 2020 exhibition. Our interactions have become more complex because we sometimes view curator Alan Yeung as a third collaborator and would like to expose ourselves to more social situations. Initially, we reflected on challenging questions on trust, homeland, and betrayal through a study of classical poetry. These aspects may present unexpected conundrums during times of conflict. Afterward, we visited public places brimming with collective memories to make experimental drawings. We engaged in a game about not being our artistic selves on a large drawing. Overall, we had bolder ideas and actions in the last exhibition in Beijing.

Hung: We prepared the show during the pandemic in 2020, so we would like to explore the changes in the inner emotions of individuals in solitude when we were confronting significant changes. In SLT 19 (2020), before commencing our drawings, we wrote positive and negative memories on strips of Xuan paper, exchanged one strip with each other, and turned the remaining strips into a paper sculpture. This sculpting act has kneaded warmth into conflicting ideas, resulting in a combined form that is poetically bound and embraced. We also invited Alan to participate in documenting and creating under certain rules and conditions. Our collaborative language became richer, incorporating more experimentation with rules in design and painting in different environments and circumstances as we attempted to break free from inherent painting habits.

.webp)

Alex Yiu is associate editor at ArtAsiaPacific.