People

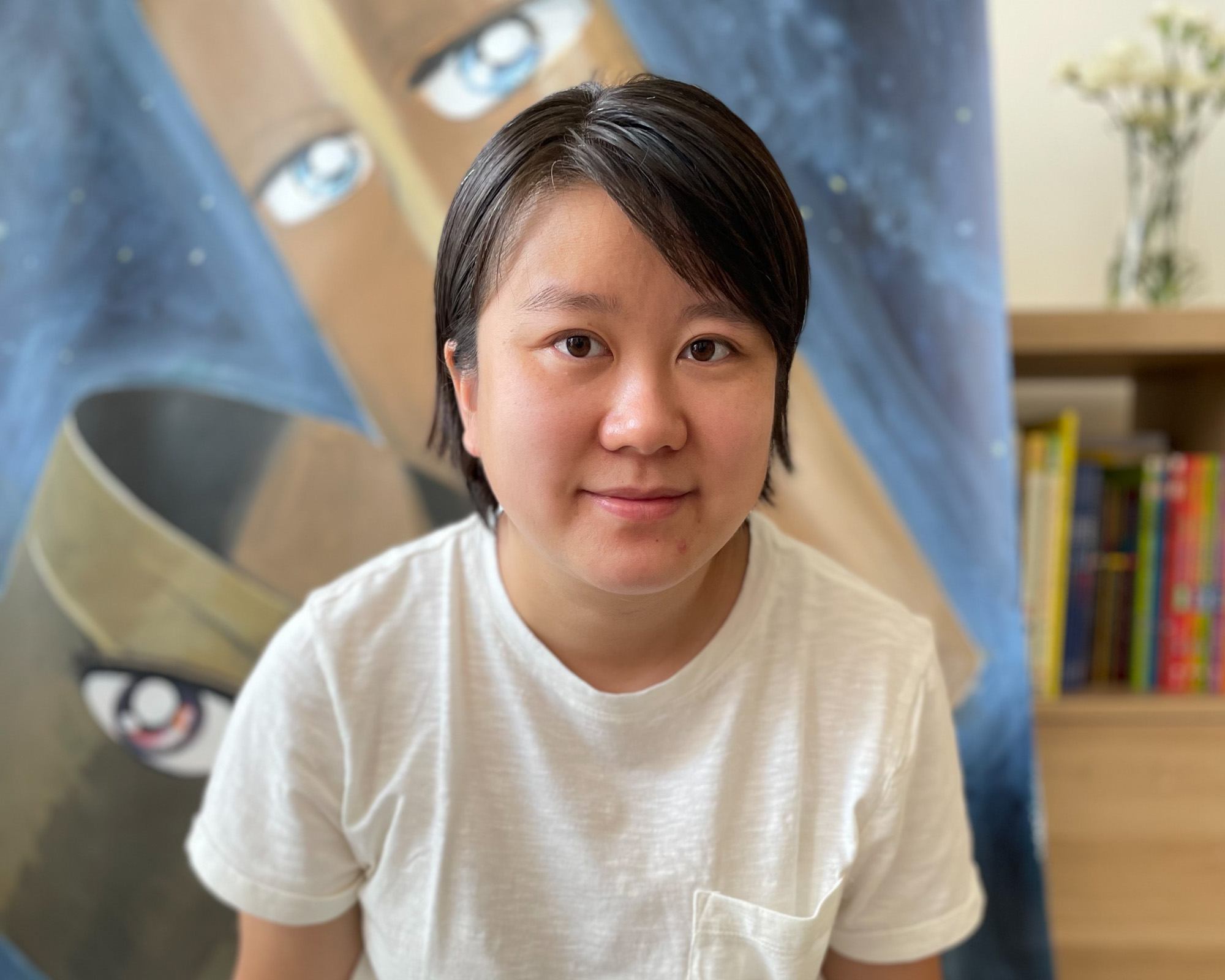

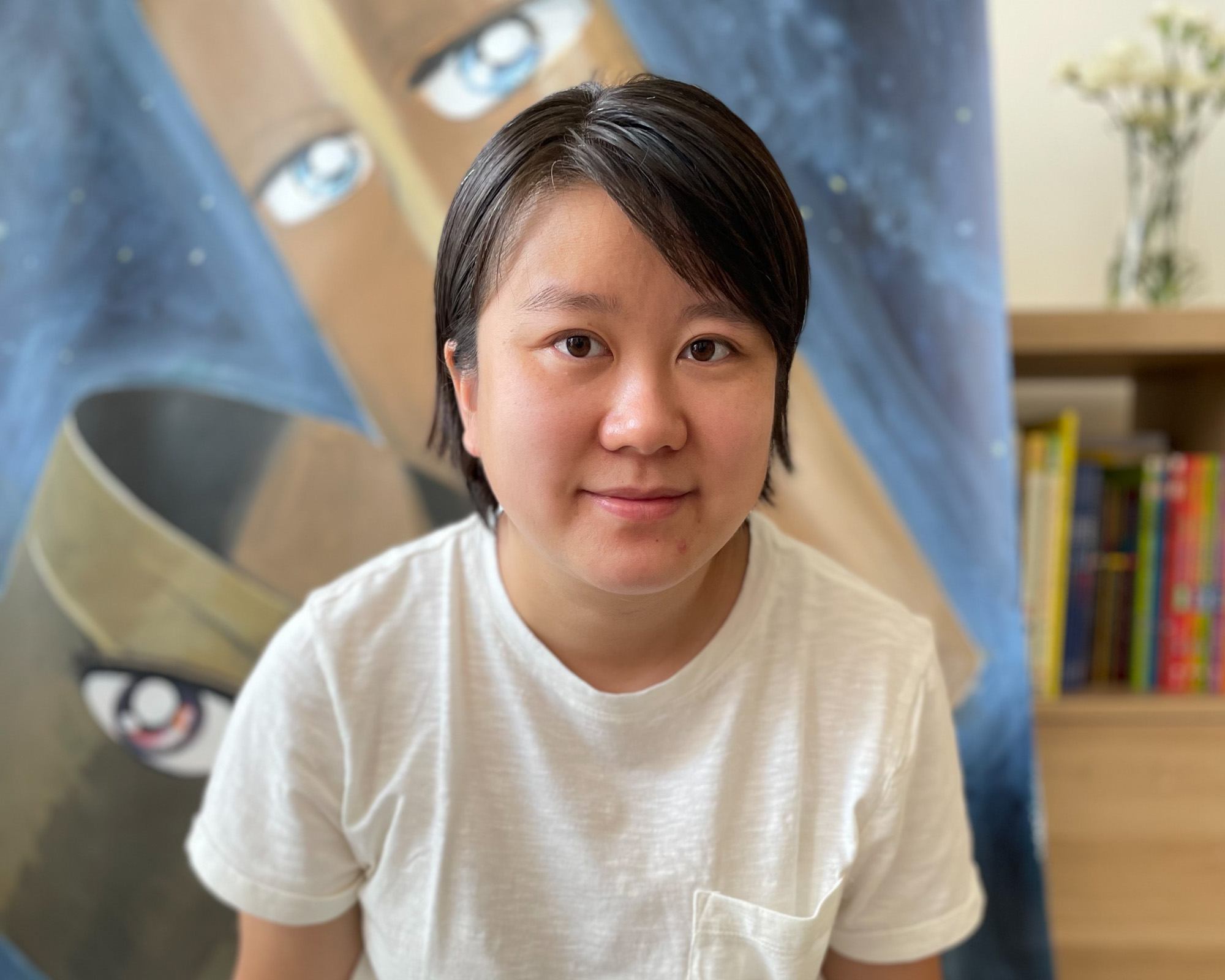

Cute Eyes, Wild Dreams: Interview with Liu Yin

Hong Kong-based, Guangzhou-born artist Liu Yin creates fantastical, cartoonish canvases in which historical figures, fictional beings, and even daily objects are incarnated as cute, innocent characters with twinkling, manga-style eyes. A graduate of the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts with a degree in painting, Liu melds her training in realism and her passion for manga imageries in works that make clever and nuanced comments on our socio-political reality. Cassie Liu spoke with the artist about her creative journey, the inspiration behind her practice, as well as the power of visual storytelling.

In the recent group exhibition “In the Labyrinth” at Edouard Malingue’s Shanghai space, you showed a group of paintings that imbue organic entities with manga-style facial features, as in The Sun (2020), Moon Night (2020), and Potatoes (2020). What’s the motivation behind affixing cartoonish faces on the nonhuman?

Sometimes when I stare at an object for a long time, I fall into a trance and my mind goes blank. In that moment, I feel I could slowly forget my existence and freely wander in a space where I can communicate with objects as equals. When I was painting the potatoes and the moon, I imagined that they were looking back at me and smiling like a child or a beautiful girl. The cartoonish eyes and relaxed expressions that I added to the composition embody a mutual gaze between the depicted objects, me, and the audience.

.jpg)

This manga-inspired visual language is very important to your practice. Many of your works render characters in kawaii style and candy colors, with special emphasis on their sparkly, oversize eyes. How did you develop this style? What kind of creative space do you think it enables?

Since I was a child, I’ve always loved Japanese anime such as Sailor Moon. I was particularly fond of the beautiful, twinkling eyes of the female characters, so I learned to draw them myself. I started artistic training when I was in primary school. My teacher at the time did not like my manga-style drawings. He said that I should observe the real people around me, mastering the realist approach before playing with pop-culture imageries. I chose to follow his teaching method, even though I never understood why this kind of visual language was not allowed and even deemed bad in the class.

As I grew older, I gradually understood that this aesthetic is loved by many, so I began to incorporate some manga elements into the realist genre I was trained in. On the one hand, I consider my work to be an eclectic product hybridizing Chinese mainstream art education and elements of popular culture. Yet on the other hand, my style of painting results from my resistance to realism and embodies my rebellion against the oppressiveness of our rigid art training.

.jpg)

You paint a lot of public figures in your work. Many of these figures are men with knowledge and power, such as Stephen Hawking in Stephen’s Fantasy (2015), and the leaders of China and Japan in The Handshake (2015). They are widely perceived as serious figures, yet you represent them as kawaii manga characters with feminine features. Are you making a point about forced masculinity and patriarchal oppression in contemporary society?

Yes and no. I guess my works seem to comment on gender politics because they reflect contrast and transformation between the masculine and the feminine. However, apart from offering critique, I also try to show empathy and solicitude for the people who are trapped inside systems of power. The public figures in my paintings are people of prominent status. Their social environment and pressuring responsibilities can force them to hide part of themselves and project an image that meets public expectations. In my works, I want to liberate them from those fixed roles.

Take Stephen Hawking for example. We all know that he was a scientist who studied outer space. I wonder if he had a more authentic self besides the rational, intellectual persona known to the public. Is it possible that Hawking was somehow religious and wished to express love and care through explorations of the cosmos? I wanted to create a heartwarming, dreamlike scene in Stephen’s Fantasy, so I surrounded him with flying angels, colorful fruits, and blossoming flowers.

The Handshake was completed in 2015, when there was some political tension between China and Japan. Captured by a photojournalist at a summit, President Xi Jinping and then-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe shook hands, but they seemed unwilling and reluctant to look at each other. I wondered what actually happened when their hands touched. Did they feel each other’s temperature and sweat? Were they shy, excited, or a little nervous? Through adding pink blushes and situating them in the baby-blue background, I tried to portray the subtle and lovely psychological experiences they possibly had.

.jpg)

In 2015, you produced a series depicting scenes from news stories about accidents, crimes, and suicides, including Woman Jumping off Building, The Policeman, and Criminal. Painted in the manga format, the subjects of these paintings seem disassociated from the cruel and painful moments they are in, resulting in an absurd, comic effect. How did you pick these news images, and why did you transform them into cartoonish scenes?

Around 2015, it became common for people to read all kinds of news via mobile phones. Every day, we consume thousands of images of strange social phenomena or current affairs. Some of these stories left a deep impression on me.

Woman Jumping off Building is inspired by a woman who jumped off a building because of anxiety and depression. Luckily, two men in the building reached out the window and got hold of her. The original picture troubled me, because it portrays the incident as an intense, dark moment full of struggles with death. I wanted to re-edit the image into a warm-hued dreamscape, where people smile happily with bubbles and lemons flying around. The result shows a morbid and twisted mentality, because the characters seem to enjoy themselves while suffering.

In a similar vein, The Policeman and Criminal are based on images from true crime programs on mainstream television stations in China. I often watch scenes of police detaining and interrogating suspects. The policemen and criminals are often portrayed as cold and ruthless, possibly because that’s what their roles should be like—the punisher and the punished. I want to present alternative images of them that show they are humans like us after all.

Your recent series tells the life story of a fictional AI character named Madeleine. It departs from your previous focus on news and historical figures. What drove you to expand the scope of your subjects from real people to a fictional character? Does fictionality give you more creative freedom?

Before Madeleine, I used to paint a historical male figure who played an important role in the society of his time. Because of his special and important status, he probably experienced a lot of limitations in expressing his true self. I tried to visualize the cute and funny side of him in my work. In Underwaist Off (2015), he wanders in nature in a sheer shirt with a rabbit in his arm, appearing all happy and relaxed. In his day, powerful figures like him liked to wear white shirts, but for fear that their nipples would be seen through the thin fabric, they would wear a white undergarment beneath the shirt that serves a similar function as women’s lingerie. Based on imagining how comfortable he would be without an undershirt, the work echoes a fashion trend that picked up around 2015. At that time, many girls argued against wearing bras, for they think it constrains their bodies both physically and psychologically.

Around 2019, I was particularly fond of Westworld, an American TV series about artificial intelligence and robots. Influenced by the plot of Westworld, I thought it would be interesting to imagine this man being reborn as an AI bot capable of doing all the things he couldn’t do in his previous life. Therefore, Madeleine’s series was created. Because he was always perceived as a masculine character in history, I recast him as a robot with a female body who wants to be beautiful and feminine. In the paintings, they are born naked like the goddess Venus in The Birth of Madeleine (2021), driving like a glamourous film actress in Madeleine Driving (2021), and posing like a sexy model in Madeleine Floating on the Antarctic Sea (2021). For me, this series is more subtle and nuanced compared to my previous paintings.

.jpg)

In the story of Madeleine, a powerful man wants to become a woman. This is not something that happens often, especially in Chinese society, where the patriarchal idea of women being inferior to men is still prevalent. Going back to your earlier comment about how your works reflect “contrast and transformation between the masculine and the feminine,” could you elaborate on what inspired you to challenge traditional fixed gender roles and hierarchies?

The previous life of Madeleine was as an important, powerful, and influential man. He was seen as a member of the upper echelons of patriarchal society. However, this does not mean that he had never been averse to social hierarchies, especially gender role differences. In my imagination, he also had a feminine side besides his masculine image. It was only the social circumstances of the time that limited him. Now that he’s reawakened as Madeleine in my work, they are free to explore their femininity.

There’s still gender discrimination against women in our society. Growing up as a girl in a more conservative and traditional environment, I felt a lot of oppression when it came to my education, career, and so on. Therefore, I guess it comes naturally to me to discuss gender politics through many of my works; I want to present stories and images that embody new possibilities.

Cassie Liu is ArtAsiaPacific’s editorial assistant.