People

Cosmos Cinema: Anton Vidokle on the 14th Shanghai Biennale

From a distance, the giant chimney of the Power Station of Art (PSA) appears to point directly to the sky, casting our gaze upwards, beyond Shanghai’s bustling cityscape. The museum is hosting the 14th Shanghai Biennale from November 9 to March 31, 2024, with a theme aptly centered around the aspiring attempt to see the cosmos as a cinema, or the cinema as the cosmos. Curated by Anton Vidokle, the co-founder of the publishing platform e-flux and an artist himself, the 14th Shanghai Biennale features works by over 80 artists from China and worldwide to celebrate filmmaking and celestial bodies, bringing Vidokle’s longterm research on cosmism and cinema to realization. In this interview, the chief curator discusses his thought process behind “Cosmos Cinema.”

You have long been interested in 19th-century Russian cosmism. Having spent more than ten years researching the concept, how did you end up with the theme “Cosmos Cinema”?

I am not a curator, but primarily an artist and filmmaker. When PSA approached me about the Biennale, I immediately thought about the research I have been doing on cosmism, works by numerous artists touching on this subject, as well as the methods and structures of filmmaking—editing, montage, scenography, sound and music, narration—to conceive of the exhibition as a film that you physically move through. When I discussed the idea with my curatorial team, we agreed this could be an important and exciting project. Lukas Brasiskis, whose background is in film studies, found an amazing short essay by the German filmmaker Alexander Kluge, “Cosmos as Cinema,” which we found extremely inspirational. He proposes that cinema is inherently cosmic, as starlight flickers in the dark sky, where the light carries information and narratives about the past, present, and even the future. Kluge goes on to ponder that before the invention of cameras or projectors, cinema already existed as the cosmos, a kind of cinema.

Growing up in Moscow in the 1970s, I often visited a movie theatre in our neighborhood called Kino Kosmos. Later, I realized that almost every city in the Soviet Union had a movie theatre called Kino Kosmos due to state planning. I bumped into another Kino Kosmos in Berlin years afterward and realized cinemas with that name could be found across the entire former Socialist block. There were numerous theatres with that name in Western Europe, South America, and even New York, where I live now, almost like an international movement. So, this intriguing connection between the cosmos and cinema exists even on a superficial level of naming commercial movie theatres. Some of the earliest films made were also cosmos-themed sci-fi fantasies about flight and space travel (films in our first screening program). Like celestial vistas, cinema is essentially aspirational, allowing us to depict scenarios that aren’t yet technologically possible.

The exhibition is very much the realization of your research on this topic. Do the artworks highlight aspects of your research, or do they instead take “Cosmos Cinema” as a reference point?

The central themes of cosmism—overcoming death and gravity, resurrection of the ancestors, observation of celestial bodies, life in the cosmos, and a desire to harmonize life on earth with the larger cosmic realm—are reflected in artworks dating back to the beginning of human civilization. When you visit the Shanghai Museum, you see an amazing collection of incredibly ancient Chinese artifacts, some of which are thousands of years old. Most of them are exquisite ceremonial, religious, and funerary objects; many are representations or ways to relate to the sky or the cosmos. Similar interests can be found in Eurasia and the Americas, Africa, and Oceania—almost everywhere. This fascination with the cosmos is present during all historical periods, including the modern era. Yet, to the best of my knowledge, this has not been the subject of a systematic study or a large-scale exhibition.

We began to map this sensibility, primarily among artists working today. We also included historical works in the Biennale, such as those from the Soviet avant-garde and historical artists from as early as a hundred years ago. But this is just the “skin of an apple:” what is below this is incredibly vast. After all, our exhibition is not only about cosmism, but also addresses a broader set of questions related to art, cosmos, and cinema. In this sense, as big as our exhibition is, it still barely scratches the surface. I hope this event can spark further conversations with curators, artists, museums, and biennials.

How do you see the Biennale in the context of Shanghai?

Interestingly, Shanghai is one of the key locations in East Asia for the early development of cinema. The first film screening took place here only a year or two after the moving image was invented. In the following decades, there was a rapid proliferation of cinemas, film production studios, the emergence of cinematographers and directors, film stars, and film journals—a whole film industry in Shanghai. This significantly contributed to how modernity was constructed in China, as the way experiences were depicted on screen influenced society’s imagination of everyday life, including social behavior, dress codes, domestic interiors, transportation means, and so forth. Accordingly, cinema has a tremendous power to change how people conceive of themselves and their societies.

The connection to the cosmos is twofold: the first and once-largest observatory in East Asia was built just outside Shanghai in 1899 by French Jesuits and still exists, fully intact, today. It was part of an international project to map the entirety of the sky by building observatories around the world to view and photograph the cosmos as seen from Earth. In this way, Shanghai has long been connected to an international network of astronomical research. At the same time, Chinese civilization has had a profound and ancient engagement with cosmological ideas. For example, the concept of legitimate social power was rooted in cosmology and the flow of cosmic energy, as well as all divination systems: I Ching, feng shui, Nine Palaces (Jiugong), medicine, religion, philosophy, and other ways to understand what animates nature and affects our bodies and lives. Interestingly, the concept of immortality is also very resonant in China, as it is one of the key spiritual goals of Taoism and a material practice of internal alchemy. While these connections may seem esoteric at first, they translate into an innate cultural desire to be in harmony with the cosmos, which is being touched upon by some of the works in the Biennale.

You mentioned earlier that the knowledge here differs from other parts of the world and that different types of work are being done globally. Considering that this Biennale has a distinct focus and theme, how would you compare it to others you've experienced, in terms of its overall development and operation?

I've primarily participated in other biennials as an artist, rather than as a curator. Therefore, curating a biennial was a very different experience. For one, it made me appreciate the work of curators and the amount of labor involved. As for the differences between this exhibition and others, using filmmaking methods to curate an art exhibition is unusual. There have been past attempts, such as an exhibition curated by Jean-Luc Godard at Centre Pompidou in which he used some elements of editing to organize the show. Another precedent is an exhibition curated by Georges Didi-Huberman at Palais de Tokyo, which similarly used elements of montage to present a show about images. I have only seen documentation of these exhibitions, so it’s hard to say how cinematic they were.

Jointly with my curatorial team, we aimed to work with the methodology of filmmaking to develop a show that is similar to an “expanded” film, a cinematic space that you move through in a psychological, emotional, immersive, and subjective space, rather than a cooler, more analytical one created by more traditional museography.

.jpg)

Do you maintain an ongoing dialogue with the artists to discuss what kind of work will be produced? Ultimately, what is your approach when dealing with these new commissions?

We discussed the concept extensively with invited artists and lenders to the exhibition. Most of the works in the show are not new commissions, and the time frame we were working with was just a few months. As a filmmaker, it takes me over a year to complete a new film, sometimes several years. So, we didn’t want to force artists to make new works quickly but instead focused on researching existing works related to our concept.

Having said that, there are important new works in the show. For example, the new film Somewhere Beyond Right and Wrong, There is a Garden. I Will Meet You There (2023) by Yin-Ju Chen, an artist from Taipei, is an amazing new work produced for our exhibition. It reflects on the healing properties of the constellation of Centaur, or Chiron, who was the king of centaurs according to Ancient Greek mythology, and was thought to be a healer. This constellation named after him is thought to have therapeutic properties of healing the body and the traumatized mind. It’s very interesting how something as remote as distant stars can be thought to affect life on Earth.

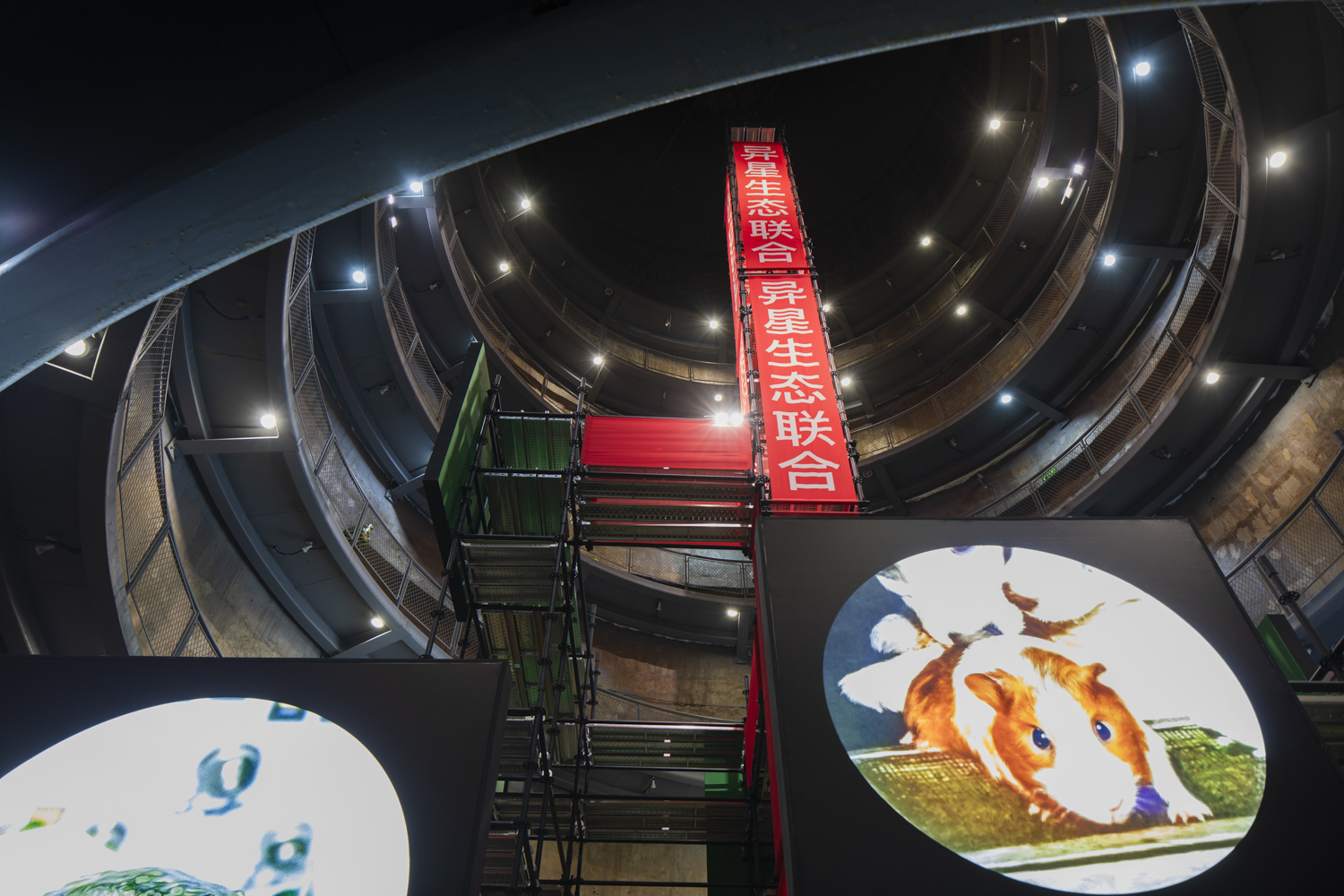

Another fascinating site-specific installation made for the show is Exo-Ecologies (2023) by Dutch artist Jonas Staal, a monument to the nonhuman species that were sent to space, intentionally or accidentally, as part of the space program. Some of these animals died in space, while others have survived and returned to Earth. This monument, reminiscent of Soviet avant-garde sculptures, is installed in the chimney of the Power Station, a very unusual space that resembles the interior of a rocket or a spaceship.

Yet another important new work is an installation The Moon (2023) by Furqat Palvan-Zade, a Uzbekistani artist and scholar. He has been researching the history of astronomy in Central Asia's Islamic world. His installation is a map of lunar craters named after important Islamic scientists and scholars, such as Avicenna and many others whose names cover the moon's surface. Islamic astronomers had an important presence in China. Kublai Khan invited a number of astronomers and astrologers from Persia and Central Asia and set up an astronomical institute at his court, which continued to function for several hundred years.

Does this exhibition serve as a realization or reflection of your research? Is the exhibition a momentary manifestation of your studies, or does it represent an ongoing process within your research on cosmism?

When I first got into cosmism in 2012, my initial idea was to curate a show. But I didn’t really know what to present, because my research was largely made up of philosophical, theoretical, and creative writing. In the end I decided to make a series of films, but the idea of an exhibition on this topic never really left my mind. Over the years, I came across many artworks, ancient and contemporary, that touch on various aspects of this subject. They don’t all fit neatly—many are rather different from each other stylistically or by their underlying logic, but this also forced me to broaden my understanding of cosmism.

More than a decade has passed since I started this research, so sometimes I want to stop and do something else. There are other important and interesting subjects in this world, so committing so much of my time to this single topic is a little scary. However, when I think of doing something else, I suddenly discover some new dimension of cosmism that pulls me back in that is just so rich and multifaceted. For instance, I recently came across the concept of astrolinguistics, which originates from cosmism: it’s a field in philology about artificial languages for communicating with other species, not necessarily on Earth. Interestingly, the first attempt to create such a universal language was made around the time of the Communist Revolution by the brothers Wolf and Abba Gordin, who lived in the Polish city of Białystok, which was once part of the Russian Empire. They created the language of “AO” to change society by introducing a new form of communication; AO did not have a word for “death,” for instance. It also seems as though they sought to create a more logical language that extraterrestrials could understand.

AO works on two levels. Human languages typically have little connection between the word (signifier) and what it refers to (signified). For example, the sound of the word “nose” doesn't inherently convey its function or form. If we want another species to understand us, it might be better to call it something that expresses its function, like “smeller.” The Gordins tried to create a totally rational, scientific language using numbers, where the signifier and signified are more logically connected. They published a grammar book and a dictionary for this language. In the end, it was used by anarchist groups for secret communication to avoid detection by the secret police.

The brothers were not only anarchist activists and theorists but also poets, making their work a blend of science, logic, politics, and futurist poetry. It straddles the line between scientific research and a mad art project, and this fusion is fascinating and mysterious. It also touches on an essential aspect of cosmism concerning the nonhuman world and how we could communicate with it. Now I would love to develop a new project about all this, maybe a film or an exhibition. So, I may never be free of the cosmos.

The 14th Shanghai Biennale, "Cosmos Cinema," takes place in the Power Station of Art, Shanghai, from November 9 to March 11, 2024.

Alex Yiu is associate editor at ArtAsiaPacific.