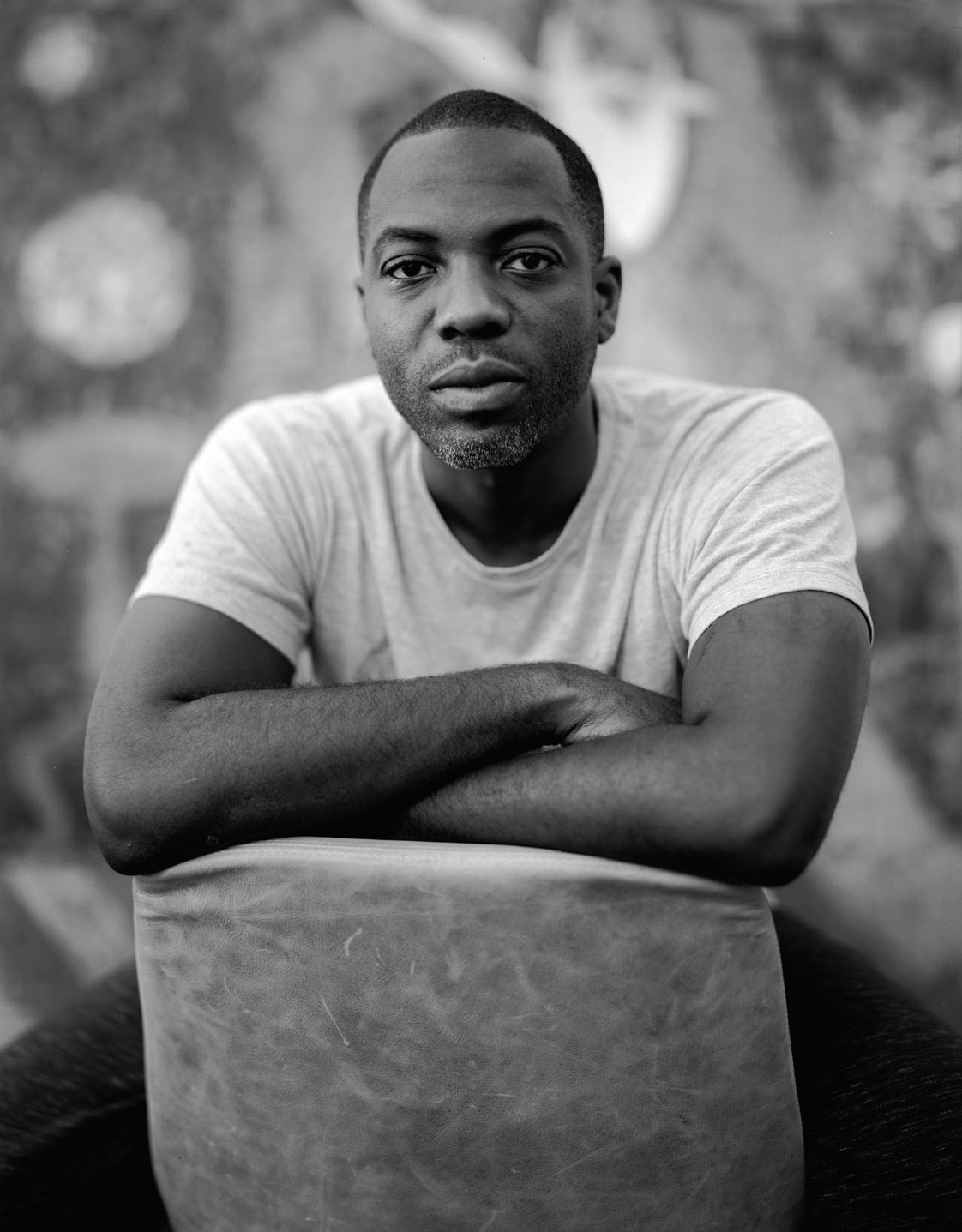

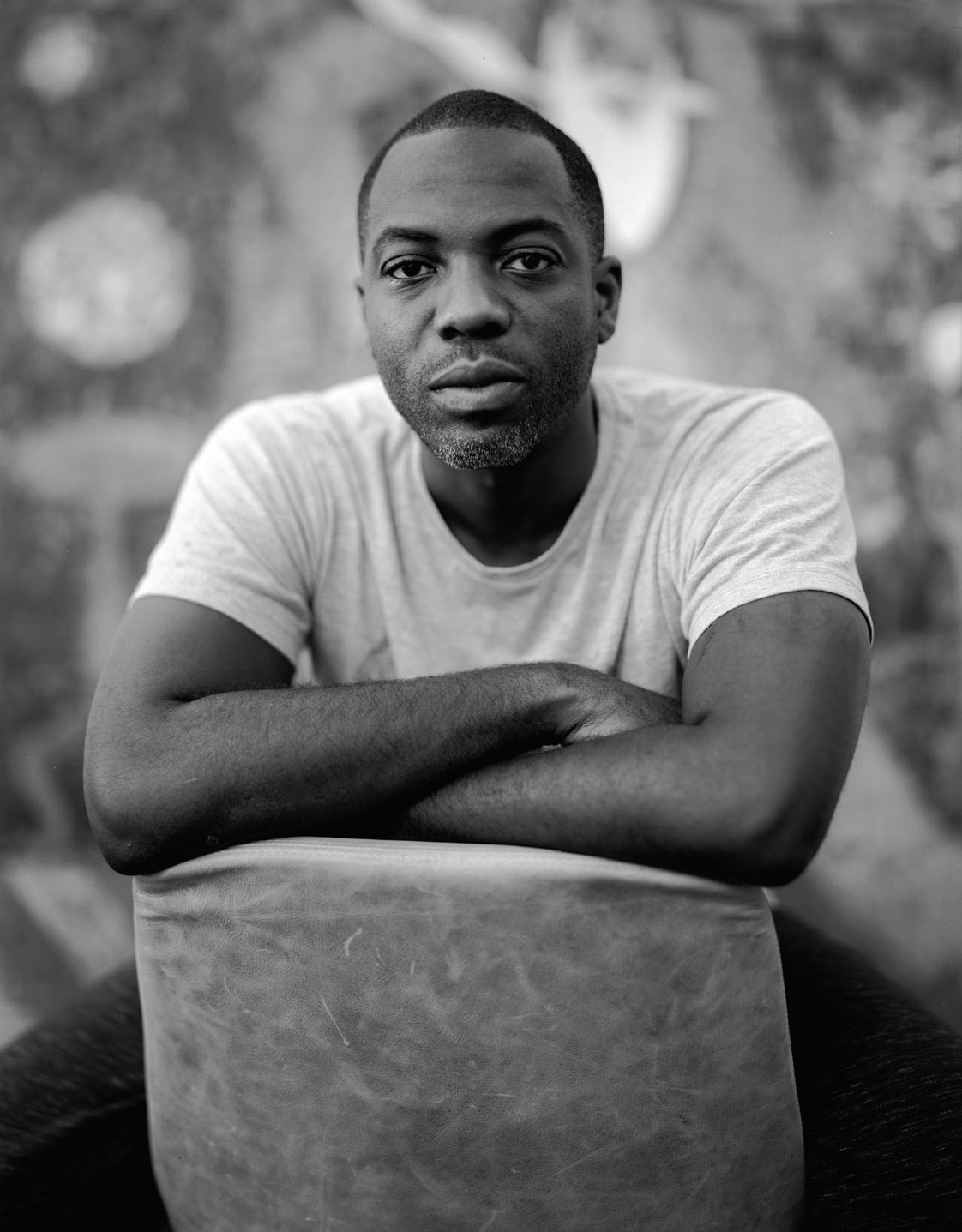

People

All the World’s a Stage: Interview with Derek Fordjour

Derek Fordjour’s multimedia painted works and installations tap into the vernacular aesthetics of American cultural life—from carnivals to sporting events, the circus, church, and the theater. His compositions of Black performers and athletes draw attention to both singular figures and bodies engaged in collective activities. With vivid colors and unique textured surfaces, Fordjour’s works highlight the roles that African Americans have historically been permitted to, or barred from, playing in specific social or cultural spaces. While drawing on the deep legacies of racism and segration in the United States, his works also explore the tensions in American culture between an ethos of individual exceptionalism and the deep bonds forged within marginalized communities. In this conversation, the artist explains how he aspires to establish empathic connections with viewers in works that touch on historical and lived experiences, while remaining inspired by his own process of creative exploration.

Several of your recent works shown in “SELF MUST DIE,” at New York’s Petzel Gallery, depict Black performers in circus or vaudeville acts, alongside athletes like the synchronized swimmers in Cadence (2020). Another series of works—Pall Bearers, Eulogy, Chorus of Maternal Grief, Procession (After Ellis Wilson) (all 2020), for instance—depict scenes of Black mourning. What are you exploring through this range of emotional expressions about the representations of Black bodies and Black communities in American culture, historically and today?

My interest in performance stems from my own attempt to grapple with a deeply personal sense of vulnerability. This is a feeling I experience keenly as an artist sharing my work publicly, hoping to achieve a universal point of access through the uniquely personal. My last show, “SELF MUST DIE,” was a direct response to the upheaval and sense of dread in the world around me. My embodied experience of navigating a world steeped in bias, predicated on complex systems of inequity, informs my worldview and guides my intuition, the catalyst of my desire to create. I try to abstain from sweeping declarations about Black life and instead amplify my humanity in ways that foster empathy and authentic connection—and that is connection to my larger community and connection to a viewer experiencing my work.

The Futility of Achievement (2020) combines elements from the world of sport, namely the trophies and jockey uniforms, and service labor, in the figure of the woman vacuuming the floor. Can we read this work as an allegory about the larger history of the struggle for African American equality in the US?

In this particular work, the specific race of the figure in the foreground is less significant than her social position and relationship to the artifacts that surround her. The intimate nature of relations between sharply contrasting socio-economic groups is an invitation to consider the function and consequence of labor. The Futility of Achievement is almost cinematic—it offers the mise en scène of a broad landscape, populated with the spoils of victory. The presence of a lone actor prompts further considerations, some of which may involve questions of equity, race, and gender; others might not. I imagine that the life experience the viewer brings to this work will determine how and what they see here.

Your process of making art is quite distinctive, beginning with cardboard pieces that you glue to the surface before adding and subtracting layers of color, newspaper, and other elements. How did you develop this layered way of working, and what does it allow you to do in terms of building a world through an image?

My process developed organically. I was initially working on newsprint because it was most affordable. Tearing and cutting the surface created the need for additional support, so I mounted paper onto canvas, but I sliced through the canvas too. Ultimately I added cardboard to provide greater support, but over time I began to add contours and varying shapes to add greater opticality to the work. I was always concerned with erosion and fracture, even when I painted with oil on wood. I would use a dremel, drill, and sanders to affect the surface layer.

How are your works displayed in “Gestalt” at Pond Society? Did you think about the show in different terms, because of the shift in cultural context from, say, New York/the US to Shanghai?

This is, by design, a straightforward painting show, with six paintings sharing one room across three walls. The experience of the show is the conversation between works, seemingly disparate subjects born of the same set of concerns. With regard to the broader context of Shanghai, I wanted to present my work concisely. I think of it as an introduction of sorts and hopefully a dialogue with the Chinese public that will continue over time.

Why did the figure of the jockey racing on a horse become important to you?

In “Gestalt,” the work The Second Factor of Production (2021) features Black jockeys and race horses. The legacy of the Black jockey in the institution of American horse racing is one that informs the politics of race relations even a century later. The attitudes towards the Black jockey at the turn of the 20th century was a direct response to Jim Crow laws and a backlash in public sentiment. After a decade of victories in the late 19th century, they were unceremoniously extricated from the sport, an absence that remains today. I invoke this history in response to the notion of Black moments, in the art world and beyond.

When audiences are engaged by your works and want to know more about your practice, who do you tell them are the artists and other cultural figures that inspired or motivated you?

I am motivated by the pursuit of catharsis, a desire to tell the truth and by my hope to edify humanity. To this end, I am infinitely inspired by human stories, literature, film, history, and more artists than I could ever list at once. The whole art historical cannon is an inexhaustible resource and its history continues to be written at the hands of artists all over the world working even now. I am humbled to trudge along in pursuit of something greater than ourselves.

After the works of “SELF MUST DIE”—and also a harrowing year in the US (and elsewhere) on many levels—do you have a sense of the directions you’re going next in your practice or things that you’d like to explore further?

I am currently working on the next iteration of paintings for a major show next year in Los Angeles with David Kordansky Gallery. I am very excited about all there is for me to learn from this new body of work. I am also slowly developing a live performance that I will be happy to share when the time comes—it could be much sooner than later. We’ll have to see!

HG Masters is ArtAsiaPacific’s deputy editor and deputy publisher.

Derek Fordjour’s “Gestalt” is on view at Pond Society, Shanghai, until July 2, 2021.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.