People

A Vessel of Stories: In Conversation with Xyza Cruz Bacani

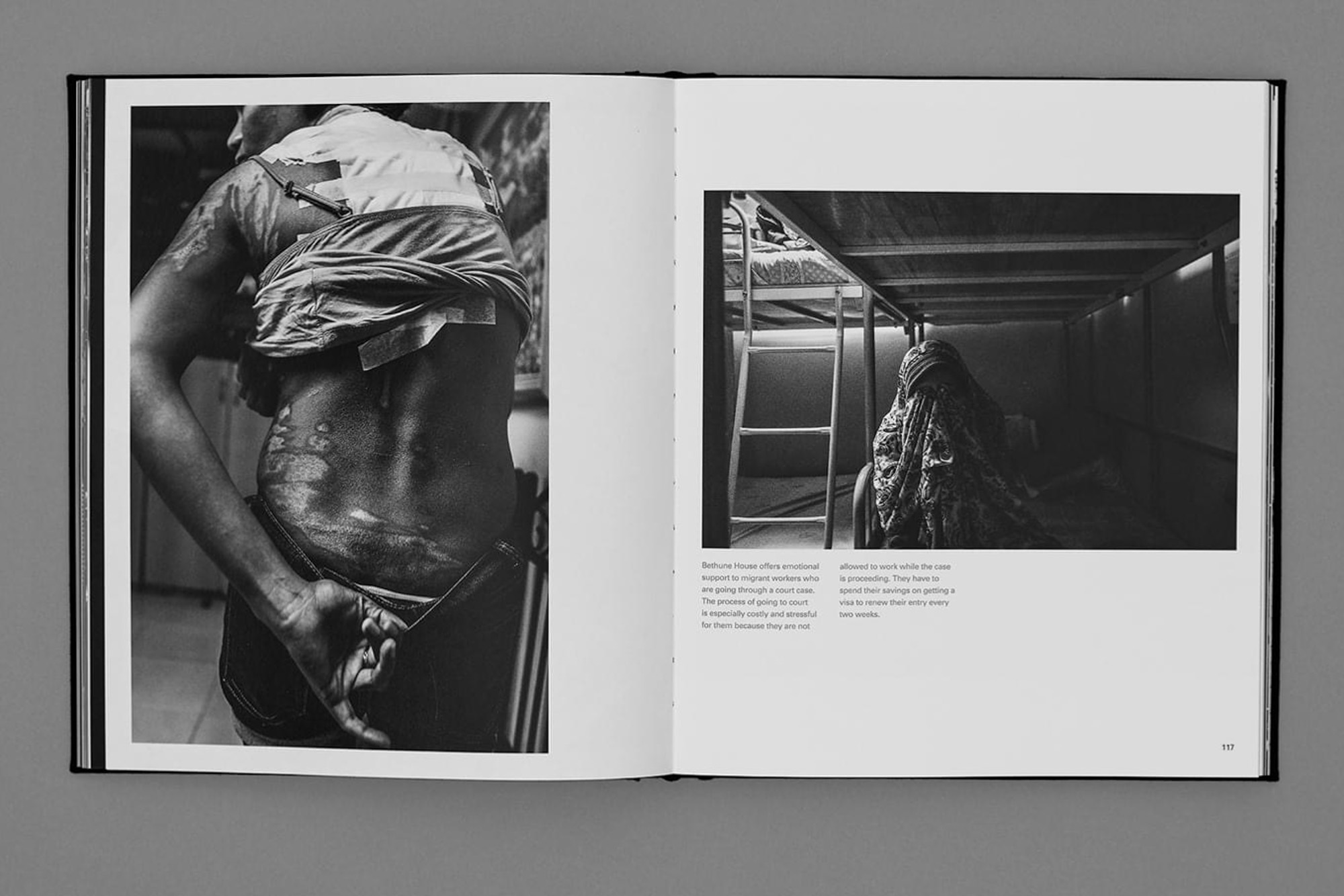

Multi-awarded Filipino artist Xyza Cruz Bacani is known for her photographs that illuminate the experiences of migrant workers and other communities rendered socially invisible. Bacani began her photographic practice in Hong Kong, where she worked as a second-generation migrant domestic worker, in the late 2000s. Her debut publication, We Are Like Air (2018), narrates the story of her mother, who spent half of her life in Hong Kong as a domestic worker, via black-and-white photographs. These images have been shown in multiple exhibitions in Hong Kong, New York, Chicago, and Taipei. As these monochromatic snapshots have broadened their reach, so has Bacani, who now divides her time between Hong Kong and New York, expanding her practice into photojournalism, writing, and painting.

I first encountered Bacani’s grayscale images of Hong Kong as a student in 2019, before meeting her through a Zoom interview a year later, when she was utilizing her time stranded in the Philippines to embark on projects related to the pandemic. Our conversation at the height of Hong Kong’s brutal Covid-19 fifth wave in March delved into her beginnings in photography, her photojournalism projects in the Philippines in 2020–21, and her working process, intertwined with reflections on power, prejudice, and representation.

How did you become a photographer? What made you pursue photography and how did you train?

This story has been told a hundred times [laughs]—I’m just kidding. I started doing photography in 2009 when I took a loan from my former employer, Mrs. Louey, to buy my first camera. I taught myself how to use it, read a lot of books, and started going around Hong Kong. I was photographing the city for my mother who has been working in Hong Kong for a long time but didn’t really know what the city looked like because she didn’t have the time to go outside. I became an eye for her. Then, I posted my photographs on Facebook. I got lucky because in 2014, a photojournalist based in California, Rick Rocamora, saw the images I posted on Facebook and sent them to the New York Times, who loved the story, so they did a feature on me. The editor, David Gonzalez, was really amazing to work with. I’m so fond of him because he was really welcoming and he was one of the people who helped me navigate the industry.

What was it about photography that drew you to it?

I was really into the arts when I was younger but growing up and coming from poverty, museums and art books were not part of my environment. I have always been fascinated with paintings because I find them calming and beautiful, so I tried sketching but when I was working as a domestic worker, I didn’t have the time to continue. You need to have a proper set-up to paint, so with photography, one thing that really clicked for me was the urgency of it—it was fast. I can see the result instantly and I really enjoy being an observer.

I think that says a lot: people appreciate different kinds of media but not all of them have the same amount of accessibility in terms of time and resources.

The first kid I took care of reminded me that I was already taking photos with a phone even before I got my first camera. The accessibility of photography really helped because even when I was working I was able to create and I liked that. Phones further democratized photography.

In the beginning of the pandemic in 2020, you worked on two photojournalism projects about the lack of available medical aid in the Philippines. One is about the only non-private doctor in your home municipality in Bambang, Nueva Vizcaya, and the other is about the increased complications of giving birth under lockdown. Could you talk more about how these projects began, and the process of getting to know these people and their stories?

I was grounded in the Philippines when the pandemic started. I was there for an assignment but decided to also go back home, visit my family, and celebrate birthdays—then Covid happened. My extended visit became a reintroduction to the place I grew up in. Since I left in 2006, I have only gone back for a week each time, and within that span of time a lot has changed, so I became a visitor to my own hometown.

In the beginning of the pandemic, I was as scared as everyone else but I felt the urgency to document what was happening. I’m very hard-headed. That’s my instinct: something is happening, we have to go and check it. I went out and no one else was outside. Then I saw nurses on duty at a checkpoint and I started talking to them. I noticed that they were only wearing cloth masks, while I was wearing an N95 just to take a walk. I felt so guilty. That was when I started documenting them.

They gave me the opportunity to follow them around, and I found out we had one community doctor for 56,000 people. The other doctors are private doctors. I decided to pitch this story to editors and, luckily, they were interested in a story from a town eight hours away from Manila, when most of the news was about the cities. It was also community nurses who told me about home birth [and the “no home birthing” policy implemented in 2008]. I didn’t even know that it wasn’t allowed in the Philippines. In this whole process, I think I gained more than what I had given, because it was a huge opportunity for me to become part of my hometown again.

The childbirth series captures very intimate moments in people’s lives. How was being a part of that?

I’m a very slow worker because I establish trust with the people I photograph. I don’t just go somewhere, take photos, then leave. I listen to them—that’s my process, that’s my practice. The photos come out as intimate because I was present.

There was an instance where one of the people who I was documenting was in a very dangerous situation. She was in labor and she texted me, “Ma’am, I feel like I’m going to give birth soon, so if you want to come [and document the process], please come.” So I drove there. The midwife and doula both said she can’t give birth at home as planned, she needed to be brought to the hospital. They were waiting for the tricycle—the only transportation that they had—but the baby was coming out, so I made the decision to intervene by offering to drive them to the hospital.

I don't usually intervene with what’s happening in the scene because I’m there to document and I subscribe to the ethics of journalism, but I made a choice to be a human at that moment. I needed to bring them to the hospital. We arrived at the hospital and within a couple of minutes she gave birth. I was honest with my editors with what happened that day.

In 2021, you followed Filipino farmers to cover “farm to table food insecurity” in the Philippines. What is “farm to table food insecurity”?

Farm to table food insecurity means there’s a disconnect between what the food farmers are producing and the consumers. This leads to farmers themselves experiencing food insecurity because, with severed logistical links, they are unable to sell their produce and earn money. We’re producing a lot but people are still hungry and the farmers are also hungry, so what is happening?

There’s a huge vegetable terminal in Nueva Viscaya. We’re called “the salad bowl of the north” because we produce a lot of vegetables for the country. Our farmers sell their produce in the vegetable terminal to distributors who bring it to Manila and other parts of the Philippines. During the pandemic, because transportation was cut off, there was no way for our farmers to trade, so all of their harvest was thrown away or donated to other people. Donating is really amazing, it’s good for the soul, but not when you’re hungry. If farmers don’t earn anything, they won’t be able to plant again.

My father is a farmer. Our family suffered a huge loss. All of our harvest was given away because there was no place to sell it during the beginning of the pandemic. The struggle of farmers is something that I already had at the back of my mind and wanted to work on, having an idea of how difficult it is for farmers in the Philippines to have a living wage with which they can feed their families properly.

I farmed mustasa [mustard greens] with my father just so I know how the process feels. At the end, we harvested the mustasa and then brought it to the market to sell. We sold everything and I earned PHP 300 (USD 6.3). All that hard work for PHP 300. I have never been so happy to have PHP 300 but I was also super disappointed.

I really hope that farmers in the Philippines will get the respect and economic gains that they deserve because they work so hard every day. Another reason why I did this project is because I want people to know where their food is coming from. The food that’s on your table—who produces it and how much work was put in for you to be able to enjoy it? It’s not magically produced, it’s someone’s blood, sweat, and tears.

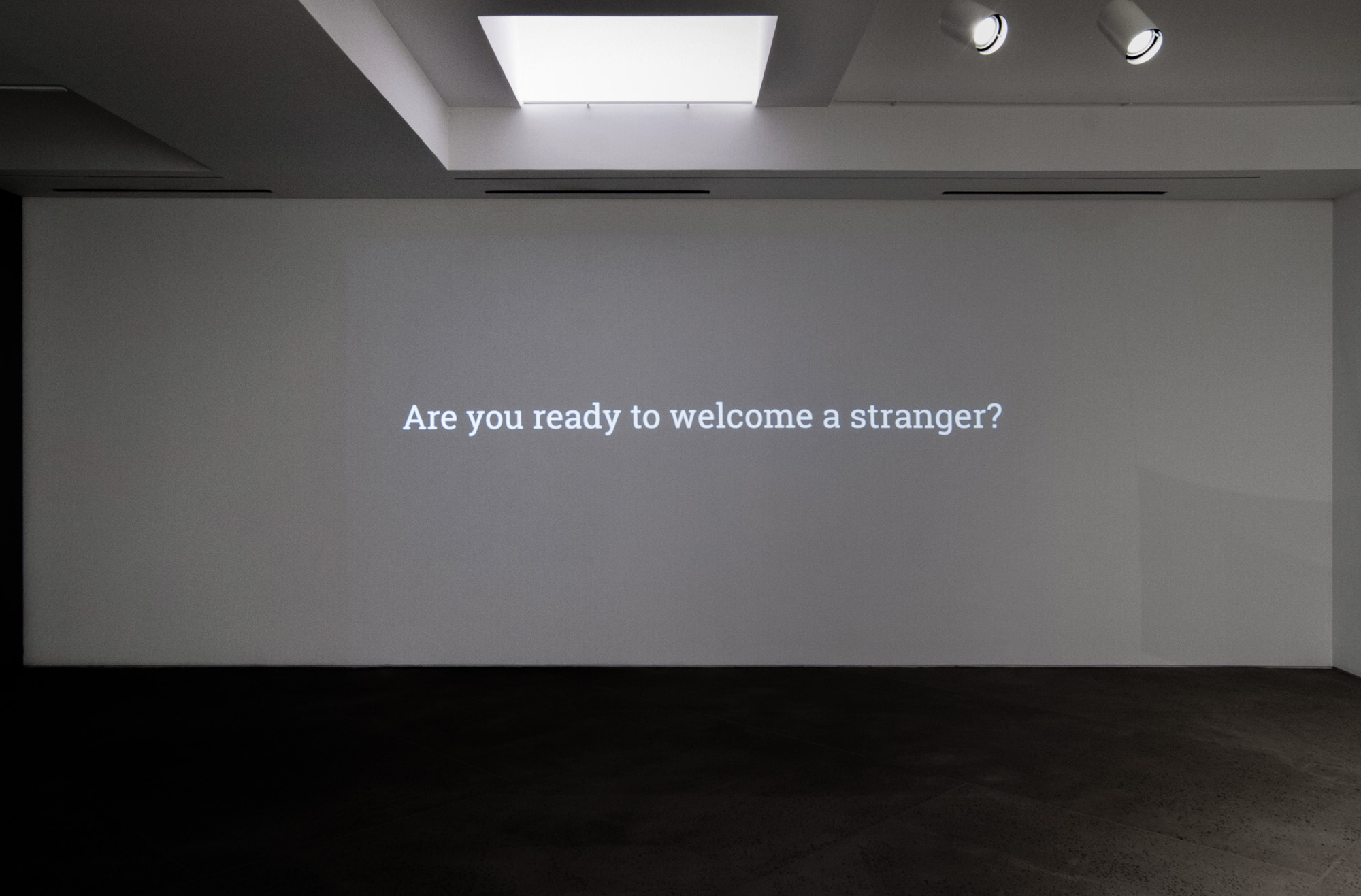

You were part of the exhibition “Curtain” (2021) at Hong Kong’s Para Site art space, where you showed photographs featuring ethnic minorities, migrant domestic workers, and laborers. Your practice has always been centered on stories that are often obscured, forgotten, or behind the curtain—why are you interested in capturing the experiences of those in the margins?

Because I’m one of them. I’m always drawn to my own people and I’ve been given the chance to be a vessel of their stories, so why not? Even with all the attention I’ve gotten because of the shift in my life, I will always be one of them.

There is often an inherent power imbalance between photographers and their subjects, especially if the subject is marginalized peoples. How do you grapple with power, consent, and social responsibility in your work?

Photography is power because the camera can be a weapon: it can empower or destroy, and it’s up to the person holding the camera what they’re going to use it for. For me, I credit my parents for teaching me strong values. One of the things I practice in my life is to do no harm. It doesn’t matter if it’s photography or personal life: I don’t like hurting people, it’s not a good feeling to have.

I try to navigate that power imbalance by making sure that when I tell my collaborators’ stories, it’s filled with dignity and it’s objective. Usually, the dignity of the people I collaborate with has been taken away by daily life alone. I don’t want them to feel like I’ve hurt them, even though some stories will hurt people no matter what, especially if it’s a story that needs to be seen. It is also important that I tell them why I’m there, because sometimes when the line gets blurry, objectivity disappears.

_013_Large.jpg)

Why do you call the people you photograph your collaborators?

I call them collaborators because I don’t like the term “subject” in photography, because who am I, the queen of England? No! I’m a documenter, a photographer. The people I photograph are collaborating with me, they are telling me their stories. It’s not like I’m there forcing them to tell me their stories, they did so with all their heart and, for me, that is collaborating, they’re sharing their life with me.

How do you maintain objectivity?

Objectivity means that you always have to fact-check. I listen to people’s stories and I fact-check because we’re all humans and people lie, I’m very aware of that. I even fact-checked my own mother for my own book! Memories are very tricky. Sometimes you recall the past by “remembering your remembering”—you recall the memory the last time you remembered it, so it can be muddled. The objectivity is also maintained by making sure that I get all sides to the story—it’s like putting together a puzzle. If something doesn’t fit, there’s a reason why it doesn’t and I try to find it.

You became known locally in Hong Kong and internationally because of your photographs of migrant domestic workers from Southeast Asia. Despite being the backbone of many economies and societies, these people, mostly women, are often overlooked and even maltreated. Currently, migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong face a series of hardships, such as being kicked out of their employers’ premises if they test positive for Covid-19. Where do you think this continuous prejudice comes from?

I’m very aware of what’s happening in Hong Kong because I’m still very connected with the community, and it makes me really sad to see that the pandemic has brought out the worst in some people. I think there are mean people in the world and that’s their personhood—we can only hope for the better. But there are more than seven million people in Hong Kong and those who kicked domestic workers out of their homes are a small minority. When people started crowdfunding to help migrant workers, that made me happy because it balanced out the bad people. I’ve also seen the NGOs and private individuals working together to help domestic workers.

The continuing prejudice is from those who are just bad, horrible people. Migrant workers are at the bottom of the totem pole and, somehow, when you’re there, you’re the receiver of shit. Have you watched zombie movies? In zombie movies, isn’t it annoying when people start fighting each other instead of helping each other? It’s similar to that. Some people think that to survive, they need to treat others badly.

Do you feel like there’s a certain weight on your shoulders with what you do, the stories you share, and the platform you have?

Ah, the pressure of representation. I always say: who am I representing, really? These are strong individuals, especially women, and I wish I could have half of their strength and courage. I only feel the pressure when a story that I’ve done cannot find a space to be shown and accessed. That’s when I feel the pressure, like did I do something wrong? I always feel responsible for the people I photograph, for my own community, because my role is a vessel—I am a conduit of stories. If I’m not able to tell their stories to others I feel like I’ve failed on my part, so I try to find solutions. I do love what I do. I don’t feel the pressure at all when I’m doing the work because I’m living a life with a purpose.

What else are you currently working on?

I am painting more. In the future, I can show them. I don’t feel like I’m good at it [laughs]! I’m also writing a novel about Hong Kong. I love Hong Kong so much. It’s crazy because most of my formative years were in the city so my memories of Hong Kong are more solid than my memories of my home country.

In times of hardship, I often end up questioning the purpose of art and what it is that keeps me in this field. What or who is it that keeps you going or inspires you?

The pandemic has changed the way I work, because it has changed the way I see the world and made me more aware of the future. I now think like an ancestor rather than a descendant. If I think as a descendant then I’m just reacting to what the situation is at the moment but as an ancestor there’s a sense of urgency. We don’t know if we’re all going to die tomorrow. I thought “I don’t know if I’m going to survive this, so might as well do something”—document my hometown, document everything that I can for the future generations, for my own descendants.

Nicole M. Nepomuceno is ArtAsiaPacific’s assistant editor.