Market

The Year of Blockbusters at Art Week Tokyo 2024

The core aim of Art Week Tokyo (AWT) (November 7–10) is to boost Japan’s visibility and accessibility in the contemporary art world, particularly in the absence of mega events that regularly draw in international collectors and audiences, as major art fairs in Hong Kong and Seoul, and biennials in Korea, Shanghai, Taipei, and Bangkok managed to do in the late 2010s. This may be changing, however, with the recurring conjunction of Art Collaboration Kyoto just ahead of AWT, offering an art fair-plus-gallery week combination package for those looking to visit Japan in November.

Along with an agenda to garner Japanese galleries more attention, AWT does substantial programming—from its own curated exhibition to a video program, symposia, studio visits, and even, this year, architectural tours. For this fourth edition in 2024, with more than 50 participating galleries and museums, the city’s museums—both private and public—provided massive and engaging exhibitions that anchored the event.

Installation view of (left) THOMAS RUFF’s d.o.pe.07 III, 2022, colarisprint on velour carpet, 267 × 200 cm, and (right) SHIGEO TOYA, Mass of Folds III, 2015, wood, ash, and acrylic, 60 × 60 × 62 cm, in "Earth, Wind, and Fire: Visions of the Future from Asia," at the Okura Museum of Art, 2024. Courtesy Art Week Tokyo.

To launch AWT, Mori Art Museum director Mami Kataoka’s curated show at the neotraditional Okura Museum of Art, the AWT Focus exhibition, “Earth, Wind, and Fire: Visions of the Future from Asia,” offered a tour through the lens of Asian cosmologies in the works of 57 artists and groups. Mirroring the venue’s architecture, Kataoka’s framework paired the neoclassical and ultra-contemporary throughout, as in the proximity of a complex, artificially generated Thomas Ruff image derived from fractal patterns, d.o.pe.07 III (2022) that resonated with the organic forms of Shigeo Toya’s ceramic sphere, Mass of Folds III (2015). Upstairs at the museum, Kataoka explored ideas of randomness as seen through the wooden constructions of Kishio Suga made from scrap wood, the elegant abstractions from salvaged Cambodian wood by Sopheap Pich, and an abstract painting by the late Taro Shinoda, inspired by Kyoto’s Katsura Imperial Villa. These were among the many connections forged across four sections addressing themes of natural cycles and energies, the invisible powers of spirits and deities, and concepts of prayer, worship, and cosmology.

Installation view of LOUISE BOURGEOIS’s Arch of Hysteria, 1993, bronze, polished patina, 83.8 × 101.6 × 58.4 cm, at "Louise Bourgeois: I have been to hell and back. And let me tell you, it was wonderful.," Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, 2024. Photos by Kenta Hasegawa. The Easton Foundation/Licensed by JASPAR, Tokyo, and VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, 2024. Courtesy Mori Art Museum.

Installation view of "Louise Bourgeois: I have been to hell and back. And let me tell you, it was wonderful.," Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, 2024. Photos by Kenta Hasegawa. The Easton Foundation/Licensed by JASPAR, Tokyo, and VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, 2024. Courtesy Mori Art Museum.

This year, Tokyo’s museums offered up big names and ambitious shows. The Louise Bourgeois retrospective at the Mori Art Museum, “I have been to hell and back. And let me tell you, it was wonderful.” featured more than 100 of the artist’s major installations and sculptures from across her lifetime—including her gigantic spiders, cages, bodily forms, and many watercolor drawings—presented with dramatic staging, as well as an intervention by contemporary artist Jenny Holzer, who created text-based videos based on Bourgeois’s writings.

Installation view of EI ARAKAWA-NASH’s "Paintings Are Popstars" at the National Art Center, Tokyo, 2024. Photo by HG Masters.

The National Art Center, Tokyo (NACT) burst onto the exhibition scene this year, showing off curatorially ambitious projects with the combination of an Ei Arakawa-Nash survey, “Paintings Are Popstars” and a Keiichi Tanaami retrospective, “Adventures in Memory.” The former was a massive survey of the Los Angeles-based contemporary artist—who has never had a solo show in his native Japan despite being internationally active for two decades—featuring his many comical and zany participatory projects. This was far from a standard exhibition: children had seemingly drawn all over the wooden floors and the artist held weekly activations of his artworks in comically ritualistic events. On the evening AWT hosted an event there, the artist was taking apart panels of an abstract painting and asking the audience to carry the pieces around; there was a string ensemble playing music, and in another performance Arakawa-Nash abducted visiting curators and had his assistants hoist them up and pass them through a hole in the surface of a giant canvas hanging on the wall as if it was a magic act. (Only one curator suffered minor injuries in the process.)

Installation view of KEIICHI TANAAMI’s "Adventures in Memory" at the National Art Center, Tokyo, 2024. Photo by HG Masters.

Downstairs at NACT, “Adventures in Memory,” the gigantic retrospective of the late artist-illustrator Keiichi Tanaami (1936–2024), who passed away shortly before the show’s opening, charted the career of this influential artist and animator. The survey revealed his signature trippy-apocalyptic style in all of its seemingly infinite manifestations from prints to sculptures, and how his practice writ large formed a template for the production-studio approach of Takashi Murakami. Tanaami’s psychedelic experimental films and many riffs on Picasso paintings were interesting moments amid his many visually dense and chaotic prints, paintings, and demonic sculptural figures.

The NACT also hosted a symposium during AWT in partnership with M+ in Hong Kong on the subject of “How has Japanese contemporary art changed since 1989?” Among the speakers were: Kathy Halbreich, former executive director of Robert Rauschenberg Foundation and a former curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York; independent curator Yukie Kamiya; and Pi Li, head of art at Tai Kwun Contemporary and formerly senior curator at M+. The symposium examined how Japanese contemporary artists were introduced abroad through institutions, as early as the late 1970s and 1980s in the UK, Europe and the US, while Pi explored China’s first exposure to contemporary Japanese artists through exhibitions in the region from the 1990s and early 2000s. The talk was a teaser to the forthcoming joint exhibition between NACT and M+ on Japanese art from 1989 to 2000.

Installation view of NISHIO YASAYUKI’s Crash Sayla Mass, 2005, fiber, plaster, steel, 280 × 400 × 600 cm, in "A Personal View of Japanese Contemporary Art: Takahashi Ryutaro Collection," at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, 2024. Photo by HG Masters.

Not to be outdone, the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo (MOT) presented 234 works from the massive private collection of 3,500-plus artworks owned by the famed psychiatrist Ryutaro Takahashi. Active since the 1990s, Takahashi collected many iconic (and massive) artworks of Japanese postwar and contemporary art, from early Yayoi Kusama paintings and performance films, to early works by Takashi Murakami from before his Superflat years and several of the early Mr. DOB paintings and sculptures. Makoto Aida’s painting on a folding screen, A Picture of an Air Raid on New York City (War Picture Returns) (1996) depicting Japanese fighter planes destroying American skyscrapers, remains an iconic, taboo-scratching work, while a giant Izumi Kato sculpture of a painted figure leaning against the wall, from 2004, presaged his commercial success. Early Chim↑Pom performance videos and photographs rounded out the many boundary-pushing works from 1990s and 2000s Japanese contemporary art that were exciting, and almost too many in quantity, to see at one moment.

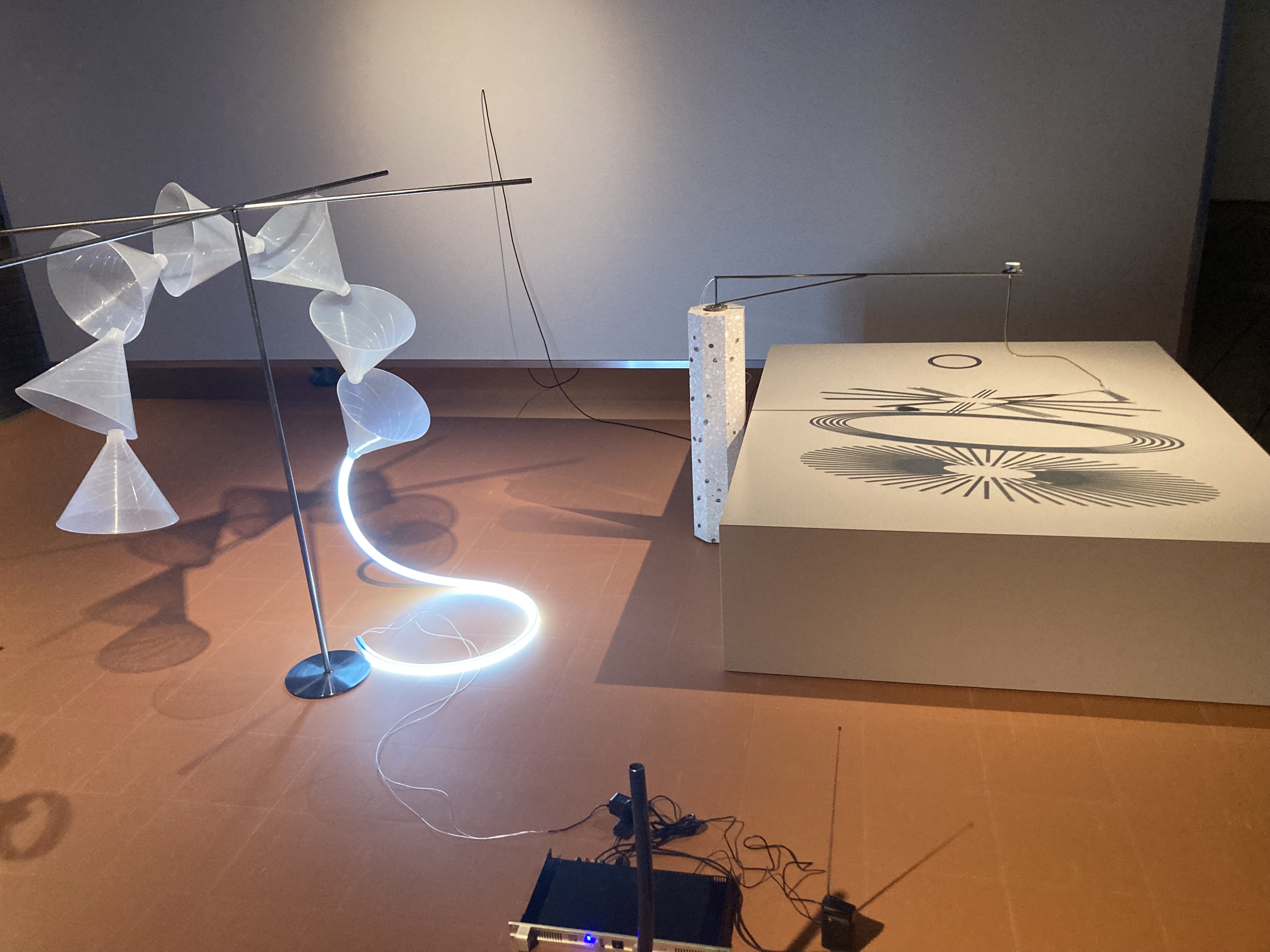

Installation view of YUKO MOHRI’s "On Physis" at the Artizon Museum, Tokyo, 2024. Photo by HG Masters.

At the private Artizon museum, the solo exhibition by Yuko Mohri, “On Physis,” was part of the museum’s “Jam Session” series where contemporary artists are invited to engage with works from the classical- and modern-focused Ishibashi collection. Using works by modernists such as Constantin Brancusi, Joseph Cornell, and Claude Monet, Mohri incorporated and elaborated on some of her previous works in dialogue with these icons. For instance, she visited one of the coastal sites in northwestern France where Claude Monet had painted the rocky cliffs. There, she recorded the sounds of the placid ocean, then programmed a piano to imitate them. She also created a largely new installation based on Marcel Duchamp’s signature work, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915–23), through mechanical components from fans to scanners, radios, and electromagnets.

Installation view of MIWA KYUSESTU XIII’s El Capitan series, 2024, at Kosaku Kanechika, Toda Building, Tokyo, 2024. Photo by HG Masters.

Next door to Artizon in Kyobashi is a new gallery cluster on the third floor of the Toda Building, housing outposts of the well-known galleries Taka Ishii, Tomio Koyama, Yutaka Kikutake, and Kosaku Kanechika. The massive office building in central Tokyo is seemingly an unlikely destination for contemporary art, but there are concerns that the area of Roppongi currently home to the gallery-filled buildings of Piramide and Complex 665—cowering in the shadow of Mori developments such as the Roppongi Hills Mori Tower—may soon be caught up in another imminent neighborhood-wide overhaul. Despite the initially disconcerting ambience in the Toda Building, the gallery spaces are flattering: Kosaku Kanechika presented the intensely wrought, thickly glazed ceramic vessels from the El Capitan series of Miwa Kyusetsu XIII, the third son of the National Living Treasure Kyusetsu XI (1910–2012). (One of these massive, thick white Hagi glazed vessels was even planted with a living pine tree.) Meanwhile, next door, Yutaka Kikutake, as part of its group show “Whispers in the Wholeness,” featured a gallery filled with cut pine branches from the northern region of Hokkaido and works by artists whom Yoshitomo Nara met during his travels. Tomio Koyama presented a show of Hiroshi Sugito, with large sculptures of fruit along with playful paintings, while Taka Ishii’s group show featured 12 artists’ interpretations of portraiture.

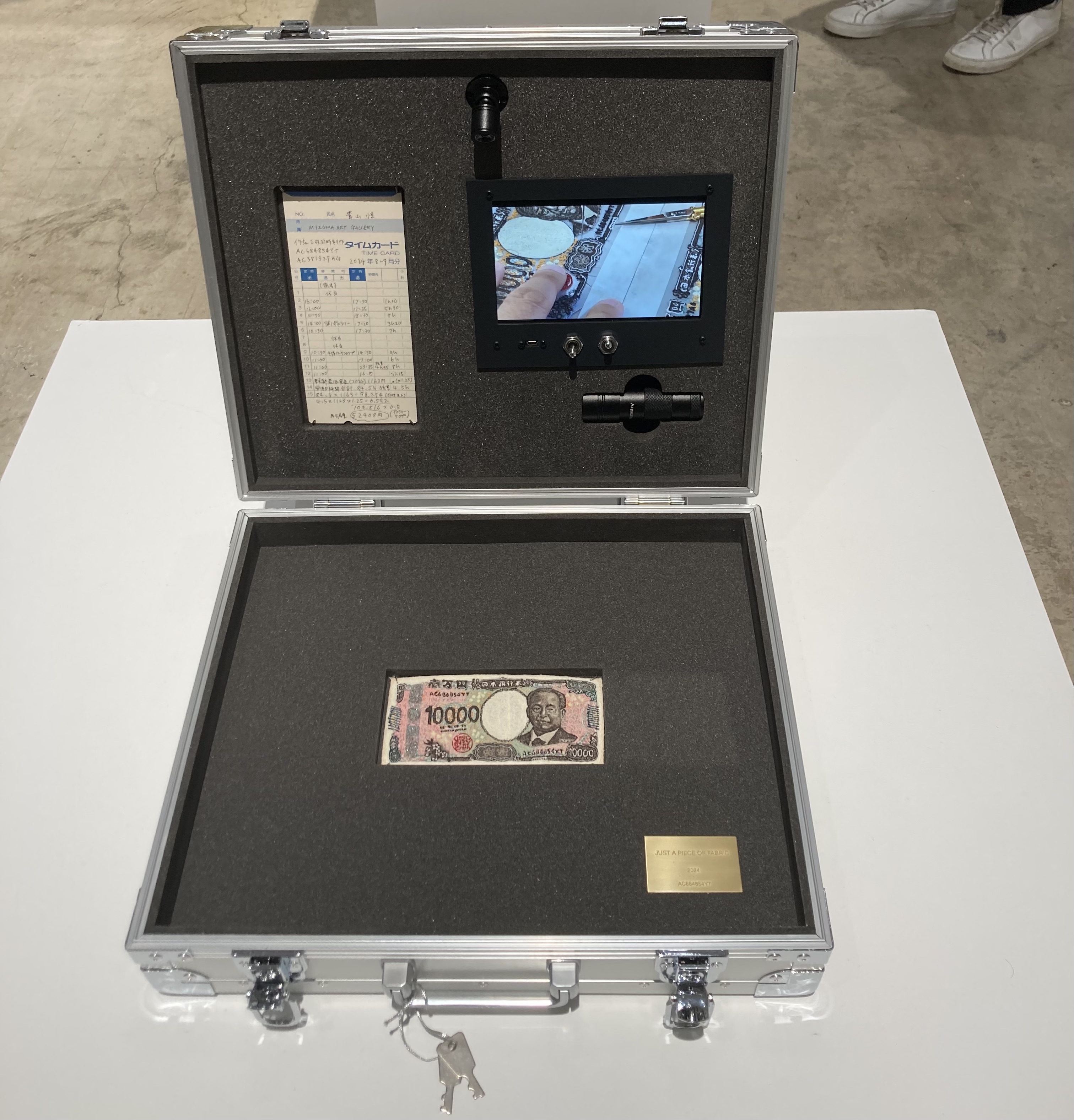

SATORU AOYAMA, Just a piece of fabric, 2022, embroidery with luminous thread on organza, video monitor, paper receipt, metal case, 44 × 44 × 15 cm, at Mizuma Art Gallery, Tokyo, 2024. Photo by HG Masters.

Artist MEIRO KOIZUMI at Mujin-to Production, Tokyo, 2024. Photo by HG Masters.

There were also standout exhibitions around the city. Mizuma Art Gallery presented textile artist Satoru Aoyama’s show “Do you believe in ‘Forever’?,” which reflected on the labor around craft through highly realistic replicas of images, objects including magazines, Japanese yen notes, receipts, and exhibition flyers. Meiro Koizumi debuted three new sculptures at Mujin-to Production of human figures made from carved styrofoam and assemblages of car engines and scrap metal posed dramatically in the space—including one scene that is modeled on a photo of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s assassin being captured—all rooted in the artist’s reflections on artificial technology. Take Ninagawa’s presentation of Kyoto artist Ryoko Aoki, “Stories About Boundaries,” offered an introduction to the artist’s practice of making delicate ink and watercolor abstractions, often paired with found objects (leaves, broken ceramics, rocks) and placed in shallow boxes.

Installation view of RYOKO AOKI’s "Stories About Boundaries" at Take Ninagawa, Tokyo. Photo by HG Masters.

Installation view of YUKIO FUJIMOTO’s BROOM (TILE), 2024, 800 unglazed ceramic titles, at Shugo Arts, Tokyo, 2024. Photo by HG Masters.

Among other intriguing surprises was to see the surreal, animated installation works by Tabaimo at Koyanagi based around a dollhouse and domestic scenes. Yuki Onodera at the Waiting Room showcased her photo-collages of scenes that she captures on her walks through the streets of Paris. ShugoArts presented veteran conceptual artist Yukio Fujimoto’s “Bloom’s Broom,” centered around the installation BROOM (TILE) (2024) of 800 unglazed tiles that you can walk on, and break, as part of the project. SCAI the Bathhouse presented a new film work and sculptures by Vajiko Chachkhiani based around stories of rural Georgia. And at Blum, the headliner of course was new works by Yoshitomo Nara, but three giant ceramic vases by Kazunori Hamana also caught the eye. Further off the beaten track is the small gallery Leesaya, which was showing paintings by Osaka-based realist Shusuke Tanaka, and a group show at Hagiwara Projects, “Dreaming Chimera,” which presented the sculptural and painting practices of eight artists, including the two artist curators Ittah Yoda and Kazuhito Tanaka.

Whether it is gallery exhibitions or the museum shows that steal the limelight year to year, in addition to AWT’s own program, there are ample reasons to visit Tokyo in early November. Perhaps add a stop in Kyoto or another destination in Japan beforehand—or travel on elsewhere in the region, as Shanghai opened its twin art fairs the same week. With cities around the world looking to stake a claim to each week of the calendar year (perhaps minus August), late October and early November looks to be an ideal season for Japan.

HG Masters is deputy editor of ArtAsiaPacific.