Market

Finding Time: Art Collaboration Kyoto Negotiates a New Here and Now

Before the opening of the second Art Collaboration Kyoto (ACK) on November 18, 2022, program director Yukako Yamashita revealed this year’s curatorial theme: “Flowers of Time.” The phrase alludes to the fantasy novel Momo (1973) about a girl who fights parasites that puff on lily-petal cigars symbolic of time stolen from humanity. Yamashita wanted to design an international art fair that emphasizes quality and connection over quantity and market-driven efficiency. Addressing the press on November 17, she explained that these events would be time better spent if they aspired to be “more than places to buy and sell art.” The 34-year-old gallerist and university lecturer, a woman of both accomplishment and promise, believes ACK should operate at a scale and pace that allows people to experience places and spend time together in ways that are genuinely meaningful.

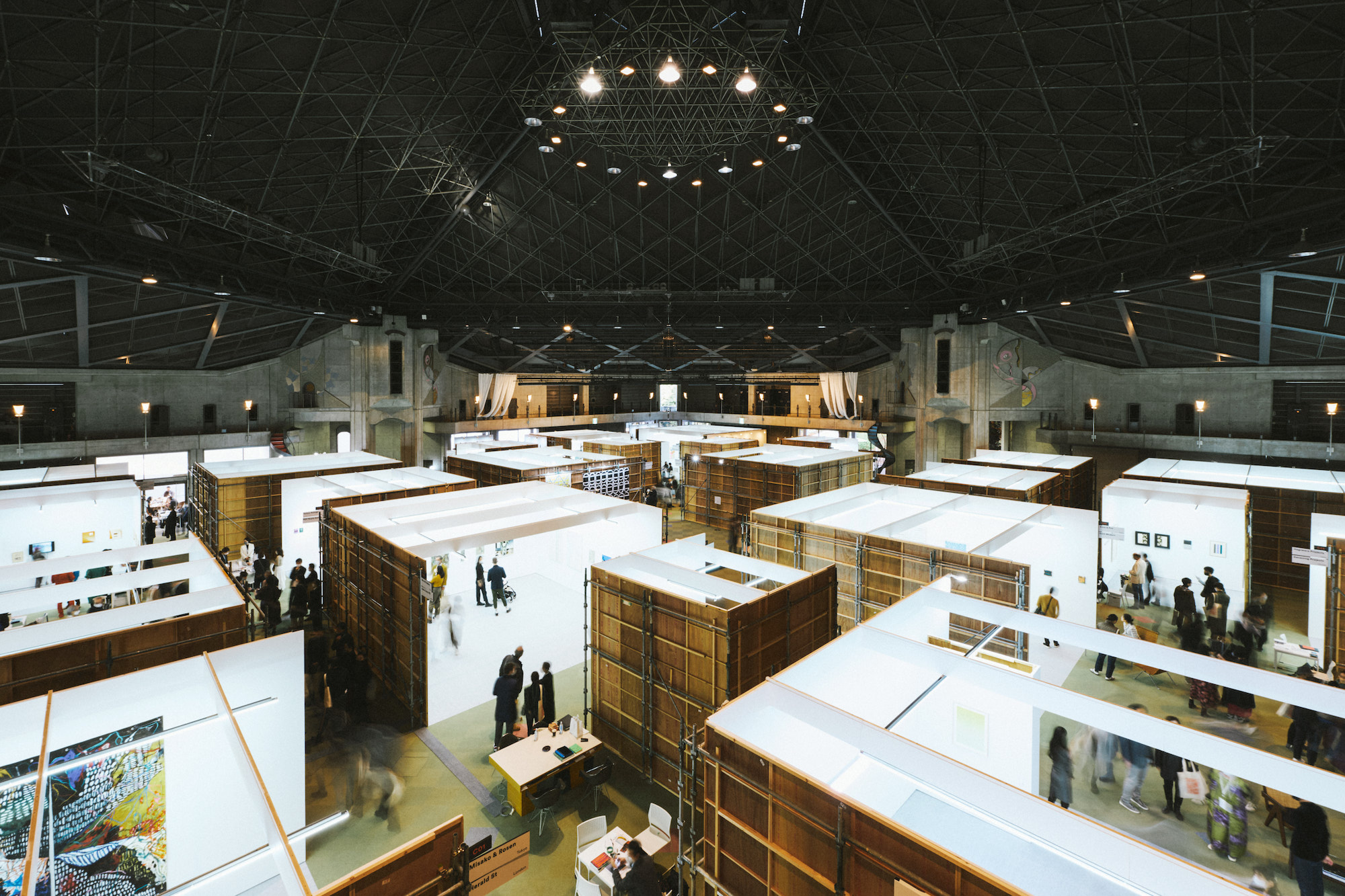

ACK 2022 was accordingly more modest in size than the typical contemporary art bonanza, with 64 galleries assembling at the ICC Kyoto Event Hall this year. As with the inaugural edition in 2021, each Japanese participant (mainly from Tokyo and the Kansai region) shared a booth with an overseas gallery of its choosing. Of the 29 “guest” galleries, 12 hailed from North America, nine from Europe, and eight from Asia. An additional six Japanese galleries joined the Kyoto Meetings section, which spotlighted artists with ties to the city. Site design by Takashi Suo (formerly of SANAA) featured booths that were open to face different directions, promoting meandering foot traffic à la Kyoto’s winding alleys. Results were strong, with visitor numbers rising by 1,000 from last year to approximately 15,000, and sales rising from JPY 250 million to over JPY 400 million.

Perhaps in keeping with the theme of time, ACK showed that it has an eye on future generations with a childcare service and Kids’ Program that included guided tours and artist-led workshops. One was guided by Aiko Miyanaga, known for her crystalized clock sculptures, who directed 8 to 13-year-olds in building plaster time capsules.

ACK also served as a conference venue where international experts discussed trends and issues of today. In this year’s Talks program, leading curators, collectors, and other specialists weighed in on the current international art scene.

The fair’s collaborative approach, realized more fully this year thanks to Japan’s recently reopened borders, suggested possibilities for redrawing the global art map. Imura Art Gallery and Mizuma Gallery narrowed the distance between their respective cities of Kyoto and Singapore in a booth that offered ceramics, paintings, and photographs by artists such as Ken+Julia Yonetani, Aya Kawato, and Jun Nguyen-Hatsushiba. Tezukayama Gallery (Osaka) and Der-Horng Art Gallery (Tainan) found symmetries in Satoru Tamura’s electric installations and Chiehsen Chiu’s grid-like paintings and atlases, all of which demonstrated striking uses of lines. Taro Nasu (Tokyo) and Sprüth Magers (Berlin) came together through language, focusing on text-based works by conceptual luminaries such as Lawrence Weiner, John Baldessari, and Jenny Holzer.

Many galleries centered their booths on a shared artist. Standing Pine (Nagoya) and Primo Marella Gallery (Milan), for example, dedicated their space to the vibrant textile compositions of Abdoulaye Konaté, the Malian artist who exhibited at this year’s Aichi Triennale. Elizabeth Denny of Denny Dimin Gallery (New York / Hong Kong) partnered with Koki Arts (Tokyo), which also carries the fabric paintings of Amanda Valdez. Denny noted a favorable response from visitors and sales that split roughly evenly. Anomaly (Tokyo) and ROH (Jakarta) showed Kei Imazu, their Japan-born, Indonesia-based painter of digitally rendered images exploring motifs of mythology, evolution, and colonialism. Imazu’s boothmates included the Indonesian collective Tromarama, which along with sculptor Noe Aoki, was selected for the Public Program.

Curated by Bellas Artes Projects founder Jam Acuzar, the Public Program showcased eight artists and groups from four countries. An audience favorite was Tromarama’s Patgulipat, an upside-down bouncy house surrounded by dangling hard hats linked to Twitter. The piece speaks to the inversion of work and leisure, and the erosion of “off” time in modern life. Another highlight was Vo Tran Chau’s installation of fabric portraits, a series that juxtaposes the colonial gaze of 19th century anthropological photographs with smartphone shots from the Vietnamese artist’s personal life.

The “Flowers of Time” exhibition took place at Hongwanji Dendoin, a temple annex usually closed to the public. Built in 1912 when Japan was rapidly globalizing, the building boasts a rare combination of Japanese, European, and Islamic architecture. Curated by Yamashita, the exhibition presented nine artists ranging from the up-and-coming to the world-renowned. Among them was Lee Mingwei, whose photography series 100 Days with Lily (1995–2022) documented his incorporation of his late grandmother’s favorite flower into every aspect of his existence.

Back at the booth for Tomio Koyama Gallery (Tokyo) and Canada (New York) on November 18, owners Koyama and Grauer recalled a Tokyo show earlier this year for their mutual painter Katherine Bradford, whose work fit elegantly with the cardboard sculptures of Hiroshi Sugito and the ceramics of Elisabeth Kley. When asked if ACK had fostered community among its international milieu, the gallerists answered affirmatively: There would be a karaoke session later that day with a highly anticipated performance from Tokyo’s Misako & Rosen, partner of London’s Herald St and collectively showing work from the Gutai-inspired painter and sculptor Naotaka Hiro. It seemed that in Kyoto at least, time would be what was made of it.

Jennifer Pastore is a Tokyo-based writer covering Japanese art and culture. She contributes to publications such as ArtAsiaPacific, Artscape Japan, and Artnet News.

* This post is presented by Art Collaboration Kyoto.