Market

Art Basel in Basel, 2015: Resource Crunch

“People are so desperate to find ways to spend their money,” a dealer quipped at 11:10 am, on Tuesday, June 16, just minutes into the first hour of Art Basel’s 2015 edition, as collectors jockeyed for artworks that may have been sold just minutes earlier—or, just as likely, even days ago. The day before Art Basel opened, another gallery director had conceded that “the fair actually began weeks ago, when we sent the PDF [of works heading to Art Basel] to our clients.” Even though the practice of pre-selling works is officially forbidden by the fair, it is something that nearly everyone does but no one will admit to; and in this super-heated market it is adding to the scarcity problems. That same multi-continental gallery was having trouble finding top-quality works to bring to Art Basel that hadn’t already been sold, or that wouldn’t already arrive in Switzerland with formidably long “reserve” lists packed with institution directors and super-collectors starting their own foundations, effectively meaning they were already off the market even before they went on display in Basel.

Art Basel’s woes are those of the one percent of the global 0.01 percent, which have been brought on by the insatiable competition for rarefied objects and the evident need of the super-rich to plough reserve cash into unregulated non-pecuniary assets, to be protected in tax-free storage havens or by the ennobled security blanket of a nonprofit foundation. Of course, not all of the 284 galleries at Art Basel have such extravagantly premium merchandise, nor can all of Art Basel’s top VIPs compete for works at this stratospheric level. Fortunately for the rest of the 0.01 percent who flock to Basel for the scene-and-be-seen atmosphere, there was USD 3.4 billion dollars worth of art on view at the Messe Halle, much of it more challenging to sell, much of it unaffected by—or possibly even suffering from—the price inflation at the highest end of the art market. Here is ArtAsiaPacific’s quick look around at some of the artworks and booths from the 2015 edition of Art Basel, midway through the hottest year of this current art-commodity bubble.

No edition of an Art Basel is complete without a bicycle wheel, or two, or 760, in this case, by AI WEIWEI. Here in the Art Unlimited section, Stacked (2012) continues a series that Ai has been creating since 2003, which evokes both the ubiquity of Yong Jiu (“Forever”) bicycles in China, as well as the vehicle’s iconic place in modernism, thanks to Marcel Duchamp.

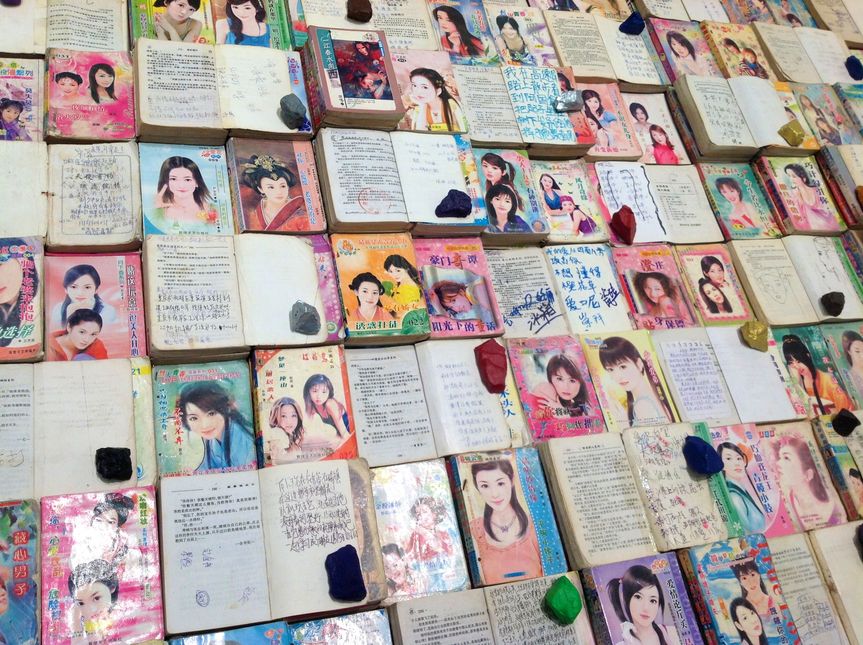

The readymade was a prevalent feature of works in Art Unlimited. LIU CHUANG’s Love Story (2006–14) comprises hundreds of pulp-fiction novels that the artist collected over eight years in Dongguan, China. These volumes are popular among the young, urban migrants who come to work in the factories. The books are inscribed with invitations to hang out, reflections on the texts themselves and diaristic entries about the readers’ lives. The artist translated certain passages onto the walls of the gallery around the books.

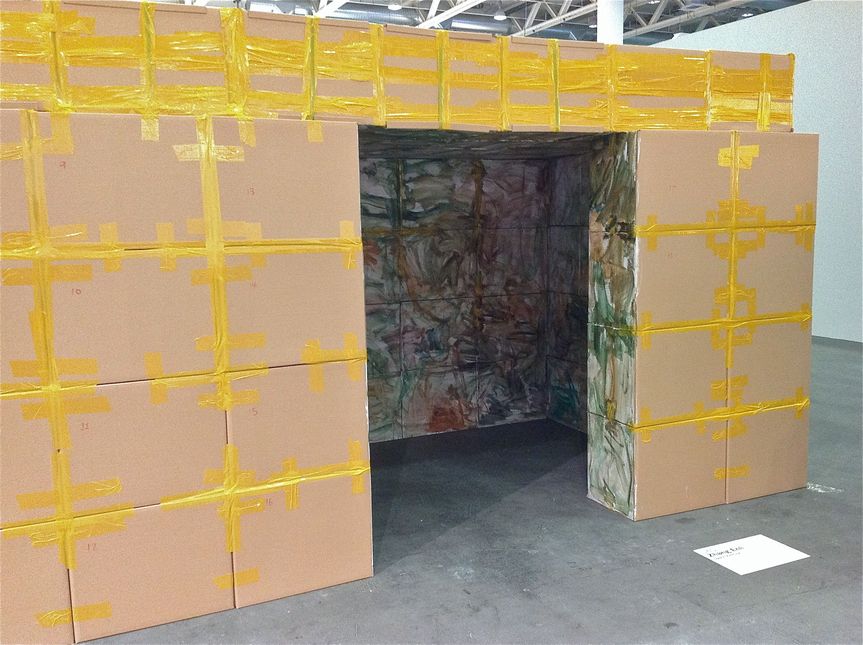

ZHANG ENLI’s Space Painting (2014) is a room made up of cardboard boxes that can be dismantled and then reassembled; its painted interior is equally (and intentionally) dismal, lit by a lone bulb.

More readymades in Art Unlimited: MAHA MULLAH’s Food for Thought ʻAlmuallaqat’ (2014), a display of used aluminum pots that she purchased in markets across Saudi Arabia. “Some are able to hold as much as three camels,” the Art Unlimited guide explains.

LIU WEI’s two-by-four-meter canvas piece The East No. 5 (2015) was supposedly an attempt to mash up ideas of monumental painting with the tranquility of landscape painting.

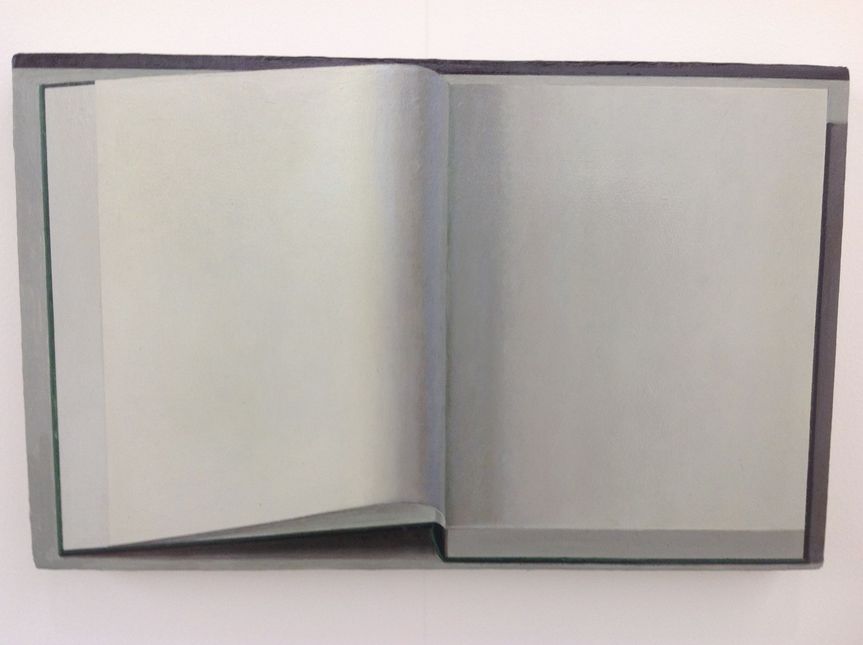

One of LIU YE’s “Book” paintings at the booth of Vitamin Creative Space (Guangzhou). Liu pays homage to Mondrian throughout his works; here the reference is suppressed down to the vertical and horizontal borders, as well as white pages of the book, which all become abstract elements.

At Nathalie Obadia (Paris) was SARKIS’s sculptural duo, Conversation Entre Mon Atelier et Joraï (2001–02), which illustrates the Istanbul-born artist’s lifelong dialogue with ritual objects.

At the booth of Tokyo’s Taka Ishii was Tree Trunk Bark, 3 (1971), a photographic print on canvas by the New York-based KUNIÉ SUGIURA, displayed with Noboru Takayama’s Underground Zoo (1969/2015), which were made from four railway ties.

In Art Statements, ABBAS AKHAVAN’s Study for a Monument (2013– ) consisted of flowers cast in bronze and arrayed on sheets of fabric at the booth of Dubai’s The Third Line gallery. The plants that Akhavan has selected are all native to the Tigris and Euphrates regions and held at the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew, in the United Kingdom.

This year has been “peak Dansaekhwa”—as the 1970s Korean monochrome movement went from being under-recognized art-historically to the Asia market’s latest “discovery” in just a few years. Here, the booth of Seoul’s PKM Gallery was dedicated solely to works by Dansaekhwa artist YUN HYONG-KEUN (1928–2008).

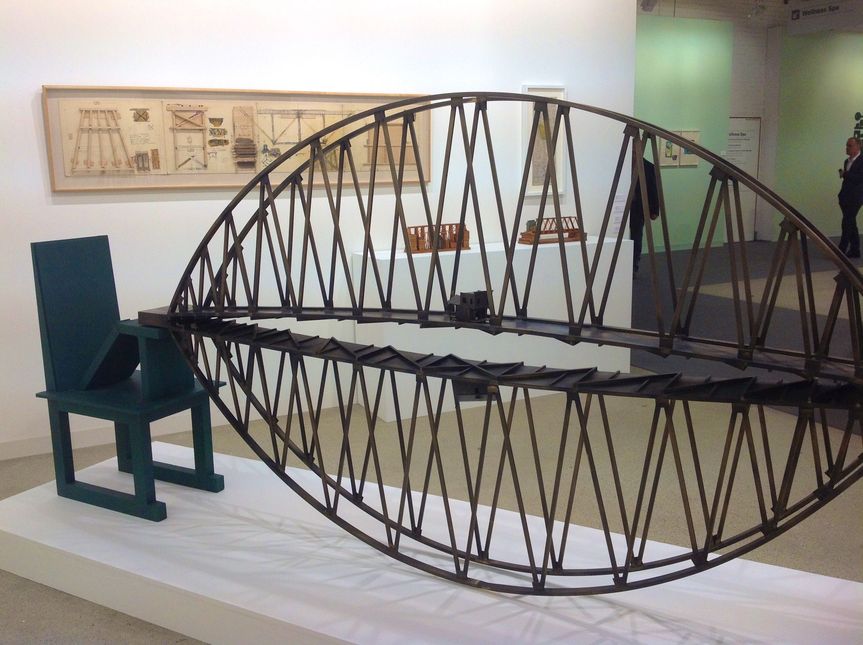

In the Art Feature section, consisting of solo presentations, Alexander Gray Associates (New York) brought late 1950s paintings by Iran-born SIAH ARMAJANI, as well as his newly produced drawings. Dominating the booth was Street Corner No. 3 (1995), incorporating some of the artist’s signature forms—chairs, bridges and houses.

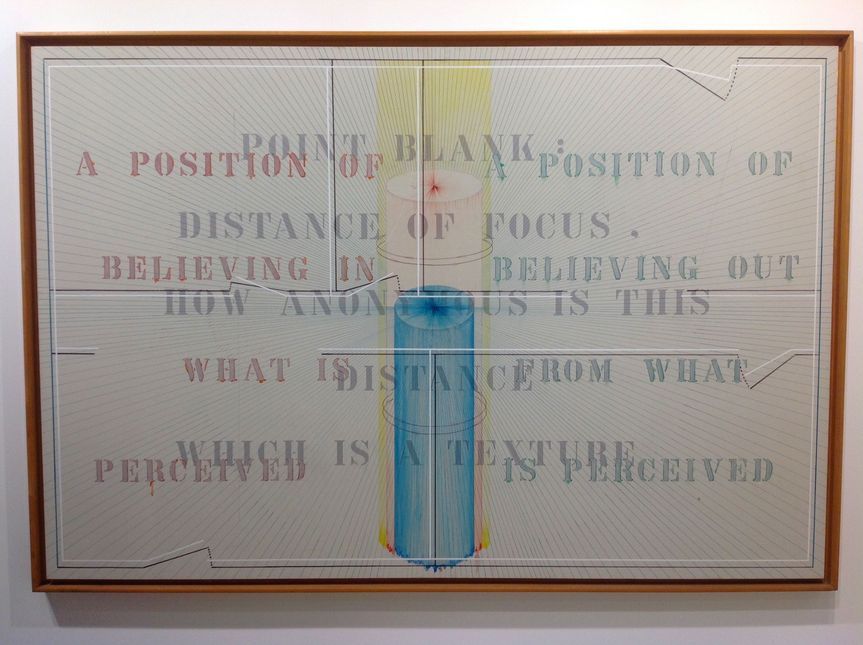

At the booth of Tokyo’s SCAI the Bathhouse was 12 O’Clock (1977) by SHUSAKU ARAKAWA (1936–2010), who was trained as an architect, and was part of Japan’s Neo-Dadaism Organizers group, before moving to New York in the early 1960s. He and his partner Madeline Gins were devoted to exploring how architecture can extend human life.

At Take Ninagawa (Tokyo) was a selection of objects by RYOKO AOKI. In the background are new “Retina/Boundary” works (1990/2015) by SHINRO OHTAKE, a series of resin-covered chromogenic prints (similar to polaroids) that he began 15 years earlier, which he has recently revived.

HG Masters is editor at large at ArtAsiaPacific.